Anthropopithecus

The terms Anthropopithecus (Blainville, 1839) and Pithecanthropus (Haeckel, 1868) are obsolete taxa describing either chimpanzees or archaic humans. Both are derived from Greek ἄνθρωπος (anthropos, "man") and πίθηκος (píthēkos, "ape" or "monkey"), translating to "man-ape" and "ape-man", respectively.

Anthropopithecus was originally coined to describe the chimpanzee and is now a junior synonym of Pan. It had also been used to describe several other extant and extinct species, among others the fossil Java Man. Very quickly, the latter was re-assigned to Pithecanthropus, originally coined to refer to a theoretical "missing link". Pithecanthropus is now classed as Homo erectus, thus a junior synonym of Homo.

History

[edit]The genus Anthropopithecus was first proposed in 1841 by the French zoologist and anatomist Henri-Marie Ducrotay de Blainville (1777–1850) in order to give a genus name to some chimpanzee material that he was studying at the time.[1]

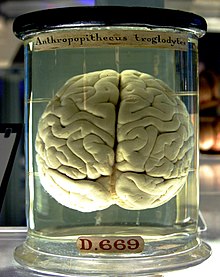

After the genus Anthropopithecus was established by De Blainville in 1839, the British surgeon and naturalist John Bland-Sutton (1855–1936) proposed the species name Anthropopithecus troglodytes in 1883 to designate the common chimpanzee. However, the genus Pan had already been attributed to chimpanzees in 1816 by the German naturalist Lorenz Oken (1779–1851). Since any earlier nomenclature prevails over subsequent nomenclatures, the genus Anthropopithecus definitely lost its validity in 1895,[2] becoming from that date a junior synonym of the genus Pan.[note 1]

In 1879,[3] the French archaeologist and anthropologist Gabriel de Mortillet (1821–1898) proposed the term Anthropopithecus to designate a "missing link", a hypothetical intermediate between ape and man that lived in the Tertiary and that supposedly, following De Mortillet's theory, produced eoliths.[4] In his work of 1883 Le Préhistorique, antiquité de l'homme (The Prehistoric: Man's Antiquity, below quoted after the 2nd edition, 1885[4]), De Mortillet writes:

Nous sommes donc forcément conduits à admettre, par une déduction logique tirée de l’observation directe des faits, que les animaux intelligents qui savaient faire du feu et tailler des pierres à l’époque tertiaire, n’étaient pas des hommes dans l’acception géologique et paléontologique du mot, mais des animaux d’un autre genre, des précurseurs de l’homme dans l’échelle des êtres, précurseurs auxquels j’ai donné le nom d’Anthropopithecus. Ainsi, par le seul raisonnement, solidement appuyé sur des observations précises, nous sommes arrivés à découvrir d’une manière certaine un être intermédiaire entre les anthropoïdes actuels et l’homme.[4]

We are therefore forced to admit, as a consequence of a logical deduction drawn from the direct observation of the facts, that intelligent animals who knew how to make fire and cut stones in the Tertiary Period, were not men in the geological and paleontological sense of the word, but animals of another kind, precursors of Man in the chain of beings, precursors to whom I gave the name Anthropopithecus. Thus, by reasoning alone, firmly supported by precise observations, we have come to discover with certainty a being intermediate between the present anthropoids and Man.

When in 1905 the French paleontologist, paleoanthropologist and geologist Marcellin Boule (1861–1942) published a paper demonstrating that the eoliths were in fact geofacts produced by natural phenomena (freezing, pressure, fire), the argument proposed by De Mortillet fell into disrepute and his definition of the term Anthropopithecus was dropped.[5] Yet the chimpanzee meaning of the genus persisted throughout the 19th century, even to the point of being a genus name attributed to fossil specimens. For example, a fossil primate discovered in 1878 by the British malacologist William Theobald (1829-1908) in the Pakistani Punjab in British India was first named Palaeopithecus in 1879 but later renamed Anthropopithecus sivalensis, assuming that these remains had to be brought back to the chimpanzee genus as the latter was being understood at the time. A famous example of a fossil Anthropopithecus is that of the Java Man, discovered in 1891 in Trinil, nearby the Solo River, in East Java, by Dutch physician and anatomist Eugène Dubois, who named the discovery with the scientific name Anthropopithecus erectus. This Dubois paper, written during the last quarter of 1892, was published by the Dutch government in 1893. In those early 1890s, the term Anthropopithecus was still being used by zoologists as the genus name of chimpanzees, so Dubois' Anthropopithecus erectus came to mean something like "the upright chimpanzee", or "the chimpanzee standing up". However, a year later, in 1893, Dubois considered that some anatomical characters proper to humans made necessary the attribution of these remains to a genus different than Anthropopithecus and he renamed the specimen of Java with the name Pithecanthropus erectus (1893 paper, published in 1894). Pithecanthropus is a genus that German biologist Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) had created in 1868.[1] Years later, in the 20th century, the German physician and paleoanthropologist Franz Weidenreich (1873-1948) compared in detail the characters of Dubois' Java Man, then named Pithecanthropus erectus, with the characters of the Peking Man, then named Sinanthropus pekinensis. Weidenreich concluded in 1940 that because of their anatomical similarity with modern humans it was necessary to gather all these specimens of Java and China in a single species of the genus Homo, the species Homo erectus.[1] By that time, the genus Anthropopithecus had already been abandoned since 1895 at the earliest.

In popular culture

[edit]The term Anthropopithecus is scientifically obsolete in the present day but did become widespread in popular culture, mainly in France and Belgium:

- In his short story Gil Braltar (1887), Jules Verne uses the term anthropopithèque (Anthropopithecus) to describe the simian aspect of one of his characters, General McKackmale:

Il dormait bien, le général Mac Kackmale, sur ses deux oreilles, plus longues que ne le comporte l’ordonnance. Avec ses bras démesurés, ses yeux ronds, enfoncés sous de rudes sourcils, sa face encadrée d’une barbe rêche, sa physionomie grimaçante, ses gestes d’anthropopithèque, le prognathisme extraordinaire de sa mâchoire, il était d’une laideur remarquable, – même chez un général anglais. Un vrai singe, excellent militaire, d’ailleurs, malgré sa tournure simiesque.

He slept well, did General MacKackmale, with both eyes shut, though longer than was permitted by regulations. With his long arms, his round eyes deeply set under their beetling brows, his face embellished with a stubbly beard, his grimaces, his semi-human gestures,[note 2] the extraordinary jutting-out of his jaw, he was remarkably ugly, even for an English general. Something of a monkey but an excellent soldier nevertheless, in spite of his apelike appearance.[6]

- In the science-fiction novel La Cité des Ténèbres (The City of Darkness), written by French journalist and writer Léon Groc in 1926, the anthropopithèques (Anthropopithecuses) are a large herd of ape-men having reached a very low degree of civilisation.

- English author George C Foster[7] makes use of both Pithecanthropus (aka Java Man) and Eoanthropus in his 1930 novel Full Fathom Five. He dates the former, a discoverer that fire can be captured, to 500,000 years ago, and the latter, the first hominid to adopt clothing, to 200,000 years ago. For the purposes of the story, the conversations of both are rendered in contemporary English.

- The Belgian comics author Hergé made the term anthropopithèque (Anthropopithecus) one of the numerous swear words of Captain Haddock in the comic album series The Adventures of Tintin.[8]

- In 2001, French singer Brigitte Fontaine wrote, sang and recorded the song titled Pipeau.[note 3] In this song, the chorus repeats the term anthropopithèque (Anthropopithecus).

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ According to the current international consensus, the genus Pan includes two species: the common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and the bonobo or dwarf chimpanzee (Pan paniscus).

- ^ The sentence ses gestes d’anthropopithèque was translated in 1959 by Idrisyn Oliver Evans as "his semi-human gestures".

- ^ The French word pipeau refers to a type of pipe, but in French slang pipeau also refers to a lie.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Bernard Wood et alii, Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution, June 2013 (single-volume paperback version of the original 2011 2-volume edition), 1056 pp.; ISBN 978-1-1186-5099-8

- ^ P. K. Tubbs, "Opinion 1368 The generic names Pan and Panthera (Mammalia, Carnivora): available as from Oken, 1816", Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature (1985), volume 42, pp 365-370

- ^ Pôle international de la Préhistoire "Le Préhistorique, antiquité de l'homme / Gabriel de Mortillet" (in French)

- ^ a b c Gabriel de Mortillet, Le Préhistorique, antiquité de l'homme, Bibliothèque des sciences contemporaines, 2nd edition, Paris, C. Reinwald, 1885, 642 p. (in French)

- ^ Marcellin Boule, "L'origine des éolithes", L'Anthropologie (1905), tome 16, pp. 257–267 (in French)

- ^ Translated from the French by Idrisyn Oliver Evans –The Best From Fantasy and Science Fiction (1959), 8th series, edited by Anthony Boucher, Ace Books, New York

- ^ "Summary Bibliography: George C. Foster". Isfdb. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ Albert Algoud, Le Haddock illustré, l'intégrale des jurons du capitaine, Casterman (collection "Bibliothèque de Moulinsart"), Brussels, November 1991, 93 p., 23,2cm x 15cm ; ISBN 2-203-01710-4 (in French)

Further reading

[edit]- John de Vos, lecture The Dubois collection: a new look at an old collection. In Winkler Prins, C.F. & Donovan, S.K. (eds.), VII International Symposium ‘Cultural Heritage in Geosciences, Mining and Metallurgy: Libraries - Archives - Museums’: “Museums and their collections”, Leiden (The Netherlands), 19–23 May 2003. Scripta Geologic, Special Issue, 4: 267-285, 9 figs.; Leiden, August 2004.

External links

[edit]- L'anthropopithèque (from the "Pôle international de la Préhistoire", archived document, in French)