Papier-mâché

Papier-mâché (UK: /ˌpæpieɪ ˈmæʃeɪ/ PAP-ee-ay MASH-ay, US: /ˌpeɪpər məˈʃeɪ/ PAY-pər mə-SHAY, French: [papje mɑʃe]; lit. 'chewed paper'), frequently written as paper mache, is a composite material consisting of paper pieces or pulp, sometimes reinforced with textiles, and bound with an adhesive, such as glue, starch, or wallpaper paste.

Papier-mâché sculptures are used as an affordable building material for a variety of traditional and ceremonial activities, as well as in arts and crafts. Many people use this as a form of decorative hobby.

Preparation methods

[edit]

There are two methods to prepare papier-mâché. The first method makes use of paper strips glued together with adhesive, and the other uses paper pulp obtained by soaking or boiling paper to which glue is then added.

With the first method, a form for support is needed on which to glue the paper strips. With the second method, it is possible to shape the pulp directly inside the desired form. In both methods, reinforcements with wire, chicken wire, lightweight shapes, balloons or textiles may be needed.

The traditional method of making papier-mâché adhesive is to use a mixture of water and flour or other starch, mixed to the consistency of heavy cream. Other adhesives can be used if thinned to a similar texture, such as polyvinyl acetate (PVA) based glues (often sold as wood glue or craft glue). Adding oil of cloves or other preservatives, such as salt, to the mixture reduces the chances of the product developing mold. Methyl cellulose is a naturally mold free adhesive used in a ratio of one part powder to 16 parts hot water and is a popular choice because it is non-toxic, but is not waterproof.

For the paper strips method, the paper is cut or torn into strips, and soaked in the paste until saturated. The saturated pieces are then placed onto the surface and allowed to dry slowly. The strips may be placed on an armature, or skeleton, often of wire mesh over a structural frame, or they can be placed on an object to create a cast. Oil or grease can be used as a release agent if needed. Once dried, the resulting material can be cut, sanded and/or painted, and waterproofed by painting with a suitable water-repelling paint.[1] Before painting any product of papier-mâché, the glue must be fully dried, otherwise mold will form and the product will rot from the inside out.

For the pulp method, the paper is left in water at least overnight to soak, or boiled in abundant water until the paper breaks down to a pulp. The excess water is drained, an adhesive is added and the papier-mâché applied to a form or, especially for smaller or simpler objects, sculpted to shape.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2024) |

Imperial China

[edit]The Chinese during the Han dynasty appeared to be the first to use papier-mâché around 200 CE, not long after they learned how to make paper. They employed the technique to make items such as warrior helmets, mirror cases, or ceremonial masks.[citation needed]

Ancient Egypt

[edit]In ancient Egypt, coffins and death masks were often made from cartonnage—layers of papyrus or linen covered with plaster.

Middle and Far East

[edit]In Persia, papier-mâché has been used to manufacture small painted boxes, trays, étagères and cases. Japan and China also produced laminated paper articles using papier-mâché. In Japan and India, papier-mâché was used to add decorative elements to armor and shields.[2]

Kashmir

[edit]The papier-mâché technique was first adopted in Kashmir in the 14th century by Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani, a Sufi mystic, who came to Kashmir during the late 14th century along with his followers, many of whom were craftsmen. These craftsmen used hand-made paper pulp from Iran.[3] Kashmir papier-mâché has been used to manufacture boxes (small and big), bowls, trays, étagères, useful and decorative items, models, birds and animals, vases, lights, corporate gifts and lot more. It remains highly marketed in India and Pakistan and is a part of the luxury ornamental handicraft market.[2] The product is protected under the Geographic Indication Act 1999 of Indian government, and was registered by the Controller General of Patents Designs and Trademarks during the period from April 2011 to March 2012 under the title "Kashmir Paper Machie".[4]

Europe

[edit]

Italy

[edit]Originating in Asia, papier-mâché reached Europe in the 15th century, where it was first used for bas-reliefs and nativity figures. By incorporating some mineral elements, artisans were able to make copies of traditional statues for devotional use, which gained popularity after the Counter-Reformation. Great Italian sculptors had already inspired artists working with papier-mâché, such as those who copied Donatello's (c. 1386-1466) bas-relief of the Virgin and Child, known as the Madonna of Verona (Louvre, RF 589, 1450 / 1500 polychrome cartapesta ). Jacopo Sansovino also used papier-mâché, for example in his bas-relief Virgin and Child (polychrome cartapesta, c.1550, Louvre: RF 746). Another Virgin and Child (with two putti) is attributed to Sansovino (1532, found in Venice, soon to be exhibited at the Ca' d'Oro). The Museo Nazionale d'Abruzzo has a Saint Jerome (c.1567-1569, polychrome papier-mâché) by Pompeo Cesura.

Baroque culture in Italy embraced papier-mâché, fostering devotion among the faithful through vivid religious imagery. In Bologna, in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, with sculptors such as Mazza (Giuseppe Maria Mazza), his pupil Angelo Piò and Filippo Scandellari, papier-mâché flourished. In the nineteenth century, Emilia-Romagna once again took over with the famous workshops in Faenza of Giuseppe Ballanti and his sons Giovan Battista Ballanti Graziani and Francesco Ballanti Graziani and the followers of Giovanni Collina and Graziani, and the workshop of Gaetano Vitené and his successors, and the latest specialists of cartapesta: Enrico dal Monte and his son Gaetano dal Monte (1916-2006)[5].

Early examples of Italian cartapasta seem to include mostly bas-reliefs. For example, there are many copies in cartapasta of Benedetto da Maiano's Madonna 'del Latte[6] (Nursing Madonna), the earliest ones attributed to his workshop, but some others dating from the early 17th century. Some were made in Tuscany, such as a polychrome papier-mâché of The Deposition of Christ with a papier-mâché Christ on a wooden cross. Another papier-mâché bas-relief representing The Beheading of Saint Paul was inspired by Alessandro Algardi, who worked almost exclusively in Rome.

The Louvre owns two very different pieces dating from the very end of the 17th century: a celestial globe (1693 signed 'Coronelli': SN 878 ; SN 340) and an earth globe (1697 signed 'Coronelli', 'P. Vincenzo, Venice': OA 10683 A)

In the 18th century, cartapesta also developed in Lecce (Puglia), where it remains a speciality. The Castle of Charles V houses the Museo della Cartapesta[7]). Religious bas-reliefs in papier-mâché were still in vogue, but a man like Giacomo Colombo, who seems to have worked mainly in Naples, made a high-relief Saint Paschal Baylón (c.1720) measuring 168cm.[8].

The places of production diversified: we know of a cartapesta 'Jesus Christ Dead in the Tomb' made in Sicily. In Siena, cartapesta products also diversified, from painted and gilded papier-mâché cherubs to boxes, trays, shelves, wall lamps and more.

In the 19th century, new objects appeared, such as table centrepieces representing a pyramid of papier-mâché and glass fruits under a glass cloche, or views of Italy, probably made for tourists, such as one of "il Colosseo ed i Fori Imperiali"[9].

England

[edit]In 1772, an English inventor, Henry Clay (apprenticed to John Baskerville in 1740 - died in 1812), patented a process for making laminated sheets of papier-mâché and treating them with linseed oil to produce waterproof panels. His technique "involved pasting sheets of paper together and then oiling, varnishing and stove-hardening them. This process produced panels suitable for coaches, carriages, sedan chairs and furniture. It was claimed that the material could be ‘sawn, planed, dove-tailed or mitred in the same manner as if made in wood". Clay, japanner, was a supplier to the Royal Family.[10] (It was probably in the 1660s that Thomas Allgood had pioneered the use of japanning on metal.)

Clay became a papier-mâché manufacturer in or before 1772 (until his death), first in Birmingham and then in London. When his patent expired in 1802 "a number of rival producers[11] set up including Jennens and Bettridge[12] who opened up in 1816 in Henry Clay's former Birmingham works". Theodore Jennens patented a process in 1847 for steaming and pressing laminated sheets into various shapes, which were then used to manufacture trays, chair backs, and structural panels, usually laid over a wood or metal armature for strength. The papier-mâché was smoothed and lacquered, or given a pearl-shell finish. The industry lasted through the 19th century.[13] This made the material more durable and it could be moulded into objects that would otherwise be difficult to manufacture, such as the globe of Jennens and Bettridge's sewing table[14], and that could withstand greater wear and tear than traditional papier mâché such as "teatrays, waiters, caddies and dressing cases … japanned and decorated with painted scenes and classical (Etruscan) and Chinoiserie subjects". Jennens and Betridge (London, Birmingham) made large tea caddies circa 1850. Other objects included cane holders, fruit bowls with mother-of-pearl inlays or papier mache head dolls by "Childs & Sons". The papier-mâché stags' heads in Powerscourt were German, though.[15]

In the 18th century, papier-mâché (that could be gilded) had begun to appear as a low-cost alternative to similarly treated plaster or carved wood in architecture, even replacing stucco in ceilings and wall decorations. Some Italian craftsmen (and the painter Giuseppe Mattia Borgnis), were invited by Francis Dashwood, 11th Baron le Despencer, around 1750 to work on St Lawrence's Church, West Wycombe and West Wycombe Park, maybe importing carta pasta to England. Robert Adam soon embraced paper stucco for elaborate interiors.

By the 19th century, two London companies—Jackson and Son, founded by fondateur George Jackson, and Charles Frederick Bielefeld’s workshop—advanced papier-mâché’s architectural use. Jackson had previously worked for Robert Adam ; he established his firm in 1780, and it became one of the leading suppliers of decorative elements, particularly for ceilings, walls, and other architectural details, using plaster and papier-mâché. Jackson and Son won a gold medal at the 1878 Paris Exposition.[16] In the 1830s, Jacob Owen's redesign of Dublin Castle featured papier-mâché work by Charles Frederick Bielefeld (1803–1864), known for his cornices and consoles at St James’s Palace. Bielefeld created papier-mâché ceiling roses, cornices, and Corinthian capitals for the castle, which were later reproduced in plaster after a fire in 1941.[17] In 1846, Bielefeld patented large, robust papier-mâché panels that could be painted for ceiling and wall decorations, or used as cabin dividers in steamboats and train carriages as well as prefabricated homes. Bielefeld "modelled, gilt and fixed" the ornaments of papier mâché of the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane in 1847 (some of which were removed in 1851).

The popularity of papier-mâché declined as electroplating offered a cheaper metal-coated alternative. McCallum and Hodson ("Summer-row, near the Town-hall, Birmingham" [18]), the last papier-mâché company, closed in 1920.

Martin Travers, the English ecclesiastical designer, made much use of papier-mâché for his church furnishings in the 1920s, in St Mary's, Bourne Street and St Augustine's, Queen's Gate, for example.

A church in Norway

[edit]Werner Hosewinckel Christie (1746-1822), a cartographer who also quarried marble and extracted lime, had his own farm workers build a large octagonal paper church known as "Hop church", on his Wernersholm estate near Bergen in 1796. It was uniquely constructed using papier-mâché as a building material (a blend of waste paper, lime, and other natural ingredients) that could mimic the look of marble. Cornelius de Jong van Rodenburgh described it: "The supporting structures are made of stone, but the church is covered inside and out in papier-mâché. In each room of the farmhouse, also made of papier-mâché, there is a large stove, and these stoves are literally made of paper".[19] Christie may have drawn inspiration from English papier-mâché techniques that he encountered on a trip to England. Unfortunately, the building deteriorated due to bad weather, and after Christie's death, the new owner, Michael Krohn, demolished both the church and mansion in 1830. Today, only Johan F. L. Dreier's watercolour of The octagonal church at Wernersholm (1827)[20] illustrates what the church once looked like.

Dolls, carton pierre items

[edit]Papier-mâché has been used for doll heads, starting as early as 1540, molded in two parts from a mixture of paper pulp, clay, and plaster, and then glued together, with the head then smoothed, painted and varnished.[21]

Carton-pierre consists of papier-mâché imitating wood, stone or bronze, especially in architecture.[22]

Mexico

[edit]

Cartonería or papier-mâché sculpture is a traditional handcraft in Mexico. The papier-mâché works are also called "carton Piedra" (rock cardboard) for the rigidness of the final product.[1] These sculptures today are generally made for certain yearly celebrations, especially for the Burning of Judas during Holy Week and various decorative items for Day of the Dead. However, they also include piñatas, mojigangas, masks, dolls and more made for various other occasions. There is also a significant market for collectors as well. Papier-mâché was introduced into Mexico during the colonial period, originally to make items for church. Since then, the craft has developed, especially in central Mexico. In the 20th century, the creation of works by Mexico City artisans Pedro Linares and Carmen Caballo Sevilla were recognized as works of art with patrons such as Diego Rivera. The craft has become less popular with more recent generations, but various government and cultural institutions work to preserve it.

Philippines

[edit]

Papier-mâché, locally referred to as taka, is a known folk art of the town of Paete,[23] the Carving Capital of the Philippines. It is said that the first known taka "was wrapped around a mold carved from wood and painted with decorative pattern."[23]

Paper boats

[edit]One common item made in the 19th century in America was the paper canoe, most famously made by Waters & Sons of Troy, New York. The invention of the continuous sheet paper machine allows paper sheets to be made of any length, and this made an ideal material for building a seamless boat hull. The paper of the time was significantly stretchier than modern paper, especially when damp, and this was used to good effect in the manufacture of paper boats. A layer of thick, dampened paper was placed over a hull mold and tacked down at the edges. A layer of glue was added, allowed to dry, and sanded down. Additional layers of paper and glue could be added to achieve the desired thickness, and cloth could be added as well to provide additional strength and stiffness. The final product was trimmed, reinforced with wooden strips at the keel and gunwales to provide stiffness, and waterproofed. Paper racing shells were highly competitive during the late 19th century. Few examples of paper boats survived. One of the best known paper boats was the canoe, the "Maria Theresa", used by Nathaniel Holmes Bishop to travel from New York to Florida in 1874–75. An account of his travels was published in the book Voyage of the Paper Canoe.[24][25]

Paper observatory domes

[edit]Papier-mâché panels were used in the late 19th century and early 20th century to produce lightweight domes, used primarily for observatories. The domes were constructed over a wooden or iron framework, and the first ones were made by the same manufacturer that made the early paper boats, Waters & Sons. The domes used in observatories had to be light in weight so that they could easily be rotated to position the telescope opening in any direction, and large enough so that it could cover the large refractor telescopes in use at the time.[26][27][28]

Applications

[edit]With modern plastics and composites taking over the decorative and structural roles that papier-mâché played in the past, papier-mâché has become less of a commercial product. There are exceptions, such as Micarta, a modern paper composite, and traditional applications such as the piñata. It is still used in cases where the ease of construction and low cost are important, such as in arts and crafts.

Carnival floats

[edit]

Papier-mâché is commonly used for large, temporary sculptures such as Carnival floats. A basic structure of wood, metal and metal wire mesh, such as poultry netting, is covered in papier-mâché. Once dried, details are added. The papier-mâché is then sanded and painted. Carnival floats can be very large and comprise a number of characters, props and scenic elements, all organized around a chosen theme. They can also accommodate several dozen people, including the operators of the mechanisms. The floats can have movable parts, like the facial features of a character, or its limbs. It is not unusual for local professional architects, engineers, painters, sculptors and ceramists to take part in the design and construction of the floats. New Orleans Mardi Gras float maker Blaine Kern, operator of the Mardi Gras World float museum, brings Carnival float artists from Italy to work on his floats.[29][30]

Costuming and the theatre

[edit]Creating papier-mâché masks is common among elementary school children and craft lovers. Either one's own face or a balloon can be used as a mold. This is common during Halloween time as a facial mask complements the costume.[31]

Papier-mâché is an economical building material for both sets and costume elements.[1][32] It is also employed in puppetry. A famous company that popularized it is Bread and Puppet Theater founded by Peter Schumann.

Military uses

[edit]Paper sabots

[edit]

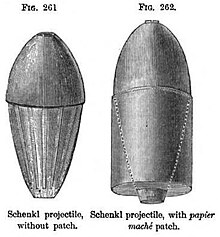

Papier-mâché was used in a number of firearms as a material to form sabots. Despite the extremely high pressures and temperatures in the bore of a firearm, papier-mâché proved strong enough to contain the pressure, and push a sub-caliber projectile out of the barrel with a high degree of accuracy. Papier-mâché sabots were used in everything from small arms, such as the Dreyse needle gun, up to artillery, such as the Schenkl projectile.[33][34]

Drop tanks

[edit]During World War II, military aircraft fuel tanks were constructed out of plastic-impregnated paper and used to extend the range or loiter time of aircraft. These tanks were plumbed to the regular fuel system via detachable fittings and dropped from the aircraft when the fuel was expended, allowing short-range aircraft such as fighters to accompany long-range aircraft such as bombers on longer missions as protection forces. Two types of paper tanks were used, a 200-gallon (758 L) conformal fuel tank made by the United States for the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, and a 108-gallon (409 L) cylindrical drop tank made by the British and used by the P-47 and the North American P-51 Mustang.[35][36]

Combat decoy

[edit]From about 1915 in World War I, the British were beginning to counter the highly effective sniping of the Germans. Among the techniques the British developed was to employ papier-mâché figures resembling soldiers to draw sniper fire. Some were equipped with an apparatus that produced smoke from a cigarette, to increase the realism of the effect. Bullet holes in the decoys were used to determine the position of enemy snipers who had fired the shots. Very high success rates were claimed for this experiment.[37]

Gallery

[edit]-

Carmen y los superhéroes de la Naturaleza, Catrina exhibited at the Interactive Museum-Labyrinth of Science and Arts in San Luis Potosí City (San Luis Potosí, Mexico)

-

Chair decorated with papier-mâché and mother of pearl, exhibited in the Museum of Carmen de Maipú (Chile)

-

Papier-mâché shark

See also

[edit]- Vycinanka (Belarusian, Ukrainian, Polish paper art)

- Russian lacquer art

- Decoupage

- Japanning

- Hanji (Korean paper art)

- Papier-mâché binding, a form of binding a book used in the 19th century

- Papier-mâché Tiara, a papal tiara made in exile for Pope Pius VII's papal coronation in a church in Venice in 1800

- Wet-folding, an origami technique that uses damp paper.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Haley, Gail E (2002). Costumes for Plays and Playing. Parkway Publishers. ISBN 1-887905-62-6.

- ^ a b Egerton, Wilbraham (1896). A Description of Indian and Oriental Armour. WH Allen & Co.

- ^ Saraf, D. N. (1 January 1987). Arts and Crafts, Jammu and Kashmir: Land, People, Culture. Abhinav Publications. p. 125. ISBN 978-81-7017-204-8.

- ^ "State Wise Registration Details Of G.I Applications" (PDF). Controller General of Patents Designs and Trademarks. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ SMBR: [1]

- ^ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Benedetto_da_maiano_e_bottega,_madonna_del_latte,_cartapesta,_1490_ca.jpg

- ^ http://www.castellocarlov.it/museo-della-cartapesta/

- ^ La Tribune de l'Art : [2]

- ^ Antonio Fogli, La cartapesta nell'arte ovvero le statue da l'arie pietose, 2012

- ^ British-history.ac: [3]

- ^ BIFMO: [4]

- ^ BIFMO: [5]

- ^ Rivers, Shayne; Umney, Nick (2003). Conservation of Furniture. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 205–6. ISBN 0-7506-0958-3.

- ^ Musée des Arts Décoratifs: [6]

- ^ "The Hall is decorated with a large collection of German and Austrian stags' heads, collected by myself at Frankfort-on-the-Main, Munich, Vienna, Buda-Pesth, and other places. … Some of those on the front of the pillars, and which have papier-mache heads, imitating life, were purchased at Munich, with the assistance of Count Arco Zinneberg, whose collection at his house in the Wittelsbacher Platz, Munich, is one of the finest in the world. (A description and history of Powerscourt, by Viscount Powerscourt, London: Mitchell and Hughes, 1903. Archive.org: [7]

- ^ Gallica: [8]

- ^ Dublincastle: [9]

- ^ Gallica: [10]

- ^ Reizen naar de Kaap de Goede Hoop, Ierland en Noorwegen 1791–97, 1802

- ^ The Picture Collection, University of Bergen

- ^ Andrews, Deborah 'Debbie'. "History of Papier Mâché Dolls". Archived from the original on 2008-02-19. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ "carton-pierre". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b "Paete's Taka : Philippine Art, Culture and Antiquities". artesdelasfilipinas.com. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ A history of paper boats, Cupery, archived from the original on 2011-07-23, retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ^ Bishop, Nathaniel Holmes, Voyage of the Paper Canoe, Project Gutenberg, archived from the original on 2020-04-20, retrieved 2020-08-28.

- ^ "Paper observatory domes". Cupery. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ^ "Columbia's New Observatory" (PDF). The New York Times. April 11, 1884. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 26, 2021. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ "The special feature of the new observatory at Columbia College will be a paper dome". The Harvard Crimson. March 19, 1883. Archived from the original on January 26, 2009.

- ^ Barghetti, Adriano (2007). 1994–2003: 130 anni di storia del Carnevale di Viareggio, Carnevale d'Italia e d'Europa (in Italian). Pezzini.

- ^ Abrahams, Roger D (2006). Blues for New Orleans: Mardi Gras And America's Creole Soul. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3959-8.

- ^ "How to Make Paper Mache Masks", Family crafts, About, archived from the original on 2017-01-09, retrieved 2009-11-03.

- ^ Bendick, Jeanne (1945). Making the Movies. Whittlesey House: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Holley, Alexander Lyman (1865), A Treatise on Ordnance and Armor, Trübner & Co

- ^ Spon, Edward; Byrne, Oliver (1872), Spon's Dictionary of Engineering, E&FN

- ^ Freeman, Roger Anthony (1970). The Mighty Eighth: Units, Men, and Machines (A History of the US 8th Army Air Force). Doubleday.

- ^ Grant, William Newby (1980). P-51 Mustang. Chartwell Books. ISBN 978-0-89009-320-7.

- ^ "H. Hesketh-Pritchard, "Sniping in France", page 46+, pub: E P Dutton".

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of papier-mâché at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of papier-mâché at Wiktionary Media related to Papier-mâché at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Papier-mâché at Wikimedia Commons- Papier-mâché – Encyclopædia Britannica