Morlachs

Morlachs (Serbo-Croatian: Morlaci, Морлаци; Italian: Morlacchi; Romanian: Morlaci) has been an exonym used for a rural Christian community in Herzegovina, Lika and the Dalmatian Hinterland. The term was initially used for a bilingual Vlach pastoralist community in the mountains of Croatia from the second half of the 14th until the early 16th century. Then, when the community straddled the Venetian–Ottoman border until the 17th century, it referred only to the Slavic-speaking people of the Dalmatian Hinterland, Orthodox and Catholic, on both the Venetian and Turkish side.[1] The exonym ceased to be used in an ethnic sense by the end of the 18th century, and came to be viewed as derogatory, but has been renewed as a social or cultural anthropological subject. As the nation-building of the 19th century proceeded, the Vlach/Morlach population residing with the Croats and Serbs of the Dalmatian Hinterland espoused either a Serb or Croat ethnic identity, but preserved some common sociocultural outlines.

Etymology

[edit]The word Morlach is derived from the Italian Morlacco (pl. Morlacchi),[2] used by the Venetians to refer to the Vlachs from Dalmatia since the 15th century.[3] The name Morovlah appears in Dubrovnik records in the mid-14th century, while in the 15th century, the abbreviated form Morlah, Morlak or Murlak is found in both Dubrovnik and Venice archives.[4] Two main theories have been put forward to explain the origin of the term.[3]

The first one has initially been proposed by the 17th-century Dalmatian historian Johannes Lucius, who suggested that Morlach would have been derived from the Byzantine Greek Μαυροβλάχοι, Maurovlachoi, meaning "Black Latins" (from Greek: μαύρο, mauro, meaning "dark", "black"), that is "Black Vlachs".[5][3] Lucius based his theory on the Doclean Chronicle, which he published and promoted. He explained that the choice made by the Venetians to use this name was made to distinguish the Morlachs from the White Latins, who would have been the inhabitants of the former Roman coastal cities of Dalmatia.[3] This theory has had a strong echo in Romanian historiography,[3] and Romanian scholars such as Cicerone Poghirc and Ela Cosma have suggested that the term "Morlachs" also meant "Northern Vlachs", derived from the Indo-European practice of indicating cardinal directions by colors.[6][7] Petar Skok suggested that while the Latin maurus is derived from the Greek μαύρος ("dark"), the diphthongs au > av indicates a specific Dalmato-Romanian lexical remnant.[8]

The other theory, mostly suggested by Croatian historiography of the previous centuries, states that Morlachs means "Vlachs near the sea", from the Serbo-Croatian more ("sea"), and vlah ("vlach").[9] The first reference to this theory comes from the 18th-century priest Alberto Fortis, who wrote extensively about the Morlachs in his book Viaggio in Dalmazia ("Journey to Dalmatia", 1774).[citation needed]

Origin and culture

[edit]

The Morlachs are first mentioned in Dalmatian documents from the 14th century, but after the Ottoman conquest of Bosnia in 1463 and especially from the 16th century onwards, "Morlach" was used by the Venetians to refer usually to the Ottoman population from the Dalmatia Hinterland, across the border from Venetian Dalmatia, regardless of their ethnic, religious or social belonging.[10][11] While their name implies some relation to the Romance-speaking Vlachs, travel accounts from the 17th and 18th century attest that the Morlachs were linguistically Slavs.[12] The same travel accounts indicate that the Morlachs were mostly of the Eastern Orthodox faith, though some were also Roman Catholic.[13] According to Dana Caciur, the Morlach community from the Venetian view, as long as they share a specific lifestyle, could represent a mixture of Vlachs, Croats, Serbs, Bosnians and other people.[14]

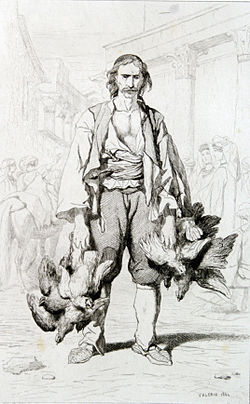

Fortis spotted the physical difference between Morlachs; those from around Kotor, Sinj and Knin were generally blond-haired, with blue eyes, and broad faces, while those around Zadvarje and Vrgorac were generally brown-haired with narrow faces. They also differed in nature. Although they were often seen by urban dwellers as strangers and "those people" from the periphery,[15] in 1730 provveditore Zorzi Grimani described them as "ferocious, but not indomitable" by nature, Edward Gibbon called them "barbarians",[16][17] and Fortis praised their "noble savagery", moral, family, and friendship virtues, but also complained about their persistence in keeping to old traditions. He found that they sang melancholic verses of epic poetry related to the Ottoman occupation,[18] accompanied with the traditional single stringed instrument called gusle.[18] Fortis gave translation of folk song Hasanaginica at the end of his book. Manfred Beller and Joep Leerssen identified the cultural traits of the Morlachs as being part of the South Slavic and Serb ethnotype.[18]

They made their living as shepherds and merchants, as well as soldiers.[19][20] They neglected agricultural work, usually did not have gardens and orchards besides those growing naturally, and had for the time old farming tools, Lovrić explaining it as: "what our ancestors did not do, neither will we".[21][20] Morlach families had herds numbering from 200 to 600, while the poorer families around 40 to 50, from which they received milk, and made various dairy products.[22][20]

Contemporary I. Lovrić said that the Morlachs were Slavs who spoke better Slavic than the Ragusans (owing to the growing Italianization of the Dalmatian coast).[23] Boško Desnica (1886–1945), after analysing Venetian papers, concluded that the Venetians undifferentiated the Slavic people in Dalmatia and labeled the language and script of the region as "Illirico" (Illyrian) or "Serviano" ["Serbian," particularly when referring to the language of the Morlachs or Vlachs in Dalmatia]. Language, idiom, characters/letters are always accompanied by the adjective Serb or Illyrian, when it is a matter of the military always is used term "cavalry (cavalleria) croata", "croato", "militia (milizia) croata" while the term "Slav" (schiavona) was used for the population.[24] Lovrić made no distinction between the Vlachs/Morlachs and the Dalmatians and Montenegrins, whom he considered Slavs, and was not at all bothered by the fact that the Morlachs were predominantly Orthodox Christian.[25] Fortis noted that there was often conflict between the Catholic and Orthodox Morlachs.[26] However some of Morlachs have passed to Islam during Turkish occupation[27] Mile Bogović says in his book that records of that time referred entire population along the Turkish-Venetian border in Dalmatia as Morlachs. Many historians, mostly Serbian, used the name Morlak and simply translate it as Serb. Almost the only difference among the Morlachs was their religious affiliation: Catholic or Orthodox.[28]

In his book, Viaggio in Dalmazia, Fortis presented the poetry of the Morlachs.[29] He also published several specimens of Morlach songs.[30] Fortis believed that the Morlachs preserved their old customs and clothes. Their ethnographic traits were traditional clothing, use of the gusle musical instrument accompanied with epic singing.[citation needed] Fortis' work started a literary movement in Italian, Ragusan and Venetian literature: Morlachism, dedicated at the Morlachs, their customs and several other aspects of them.[31]

On Krk island, where a community was settled from the 15th century, two small samples of the language were recorded in 1819 by the local priest from Bajčić in the forms of Lord's Prayer and Hail Mary, as shown below:[32]

“Cače nostru, kirle jesti in čer

Neka se sveta nomelu tev

Neka venire kraljestvo to

Neka fiè volja ta, kasi jaste in čer, asa si prepemint

Pire nostre desa kazi da ne astec

Si lasne delgule nostre, kasisi noj lesam al delsnic a nostri

Si nun lesaj in ne napasta

Nego ne osloboda de rev. Asasifi.”

"Sora Maria pliena de milosti Domnu kutire

Blagoslovitest tu intre mulierle, si blagoslovituj ploda dela utroba ta Isus

Sveta Maria, majula Domnu, rogè Domnu za noj akmoče si in vrajme de morte a nostru. Asasif!"

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The use of Morlachs is first attested in 1344, when Morolacorum are mentioned in lands around Knin and Krbava during the conflict between the counts of the Kurjaković and Nelipić families.[33] The first mention of the term Morlachs is simultaneous with the appearance of Vlachs in the documents of Croatia in the early 14th century; in 1321, a local priest on the island of Krk granted land to the church ("to the lands of Kneže, which are called Vlach"), while in 1322 Vlachs were allied with Mladen Šubić at the battle in the hinterland of Trogir.[34] According to Mužić in those early documents there is no identifiable differentiation between the terms Vlach and Morlach.[35] In 1352, in the agreement in which Zadar sold salt to the Republic of Venice, Zadar retained part of the salt that Morlachi and others exported by land.[36] In 1362, the Morlachorum, settled, without authorization, on lands of Trogir and used it for pasture for a few months.[37] In the Statute of Senj dating to 1388, the Frankopans mentioned Morowlachi and defined the amount of time they had for pasture when they descended from the mountains.[38] In 1412, the Murlachos captured the Ostrovica Fortress from Venice.[39] In August 1417, Venetian authorities were concerned with the "Morlachs and other Slavs" from the hinterland, who were a threat to security in Šibenik.[40] Authorities of Šibenik in 1450 gave permission to enter the city to Morlachs and some Vlachs who called themselves Croats who were in the same economic and social position at that time.[41]

According to scholar Fine, the early Vlachs probably lived on Croatian territory even before the 14th century, being the progeny of romanized Illyrians and pre-Slavic Romance-speaking people.[42] During the 14th century, Vlach settlements existed throughout much of today's Croatia, from the northern island Krk, around the Velebit and Dinara mountains, and along the southern rivers Krka and Cetina. Those Vlachs had, by the end of the 14th and 15th century, lost, their Romance language, or were at least bilingual.[43][nb 1] As they adopted Slavic language, the only characteristic "Vlach" element was their pastoralism.[47][nb 2] The so-called Istro-Romanians continued to speak their Romance language on the island of Krk and villages around Lake Čepić in Istria,[49] while other communities in the mountains above the lake preserved the Shtokavian-Chakavian dialect with Ikavian accent from the southern Velebit and area of Zadar.[50][51][nb 3] Today's Istro-Romanians may be a residual branch of the Morlachs.[54]

The Istro-Romanians, and other Vlachs (or Morlachs), had settled Istria (and mountain Ćićarija) after the various devastating outbreaks of the plague and wars between 1400 and 1600,[55] reaching the island of Krk. In 1465 and 1468, there are mentions of "Morlach" judge Gerg Bodolić and "Vlach" peasant Mikul, in Krk and Crikvenica, respectively.[56] In the second half of the 15th century, Catholic Morlachs (mostly Croatian Vlachs) migrated from the area of southern Velebit and Dinara area to the island of Krk, together with some Eastern Romance-speaking population.[57] The Venetian colonization of Istria (and Ćićarija) occurred not later than the early 1520s,[55] and there were several cases when "Vlachs" returned to Dalmatia.[58]

16th century

[edit]Although the first Ottoman invasion of Croatia took place in the early 15th century, the threat to Dalmatian towns began only after the conquest of Bosnia in 1463. During the Ottoman–Venetian war of 1499-1502, a considerable demographic shift took place in the Dalmatian hinterland, leading to the abandonment of many of the region settlements by their previous inhabitants.[59] During the years following the Ottoman conquest of Skradin and Knin in 1522, local Ottoman rulers started to resettle the depopulated areas with their Vlach subjects.[60] Referred to as Morlachs in the Venetian records, the newcomers to Šibenik hinterland (Serbo-Croatian: Zagora) came from Herzegovina and among them, three Vlach clans (katuns) predominated: the Mirilovići, the Radohnići, and the Vojihnići.[61]

At the same time, the Austrian Empire established the Military Frontier, which served as a buffer zone against Ottoman incursions.[62] Thus, other Vlachs, Slavicized Vlachs and Serbs fled the Ottomans and settled in this area.[63] As a consequence, Vlachs[nb 4] were used by both the Ottomans on one side, and Austria and Venice on the other.[65]

From the 16th century onwards, the name "Morlach" became specifically used by the Venetians to refer the any inhabitant of the hinterland, as opposed to those of the coastal towns, in an area stretching from the north of Kotor to the Kvarner Gulf region. In particular, the area around the Velebit mountain range was largely populated by Morlachs, to the extent that the Venetians called it Montagne della Morlacca ("mountain of the Morlachs"), while they used the name Canale della Morlacca to designate the Velebit Channel.[66]

Between the end of the War of Cyprus in 1573 and the start of the Cretan War in 1645, trading relations between the Venetian Republic and the Ottoman Empire improved significantly. As the border region between the two, Dalmatia became a dynamic center of these relations. In particular, Morlachs from the hinterland played an important role in trade, bringing corn, meat, cheese and wool to towns like Šibenik, and buying fabrics, jewelry, clothing, delicacies and, above all, salt.[67] During this period, a significant number of Morlachs immigrated to the Venetian side near Šibenik, either temporarily or permanently. These migrations were mainly in search of employment as soldiers or servants, or through "mixed" marriages. Most of these Morlach migrants came from the areas of Zagora, Petrovo Polje, the Miljevci plateau and the Cetina valley.[68]

In 1579, several groups of Morlachs immigrated and requested to be employed as military colonists.[69][better source needed] Initially, there were some tensions between these immigrants and the established Uskoks.[69] In 1593, provveditore generale (Overseer) Cristoforo Valier mentioned three nations constituting the Uskoks: the "natives of Senj, Croatians, and Morlachs from the Turkish parts".[70]

17th century

[edit]

At the time of the Cretan War (1645–69) and Morean War (1684–99), a large number of Morlachs settled inland of the Dalmatian towns, and Ravni Kotari of Zadar. They were skilled in warfare and familiar with local territory, and served as paid soldiers in both Venetian and Ottoman armies.[71] Their activity was similar to that of the Uskoks. Their military service granted them land, and freed them from trials, and gave them rights which freed them from full debt law (only 1/10 yield), thus many joined the so-called "Morlach" or "Vlach" armies.[72]

At the time, some notable Morlach military leaders[nb 5] who were also enumerated in epic poetry, were: Janko Mitrović, Ilija and Stojan Janković, Petar, Ilija and Franjo Smiljanić, Stjepan and Marko Sorić, Vuk Mandušić, Ilija Perajica, Šimun Bortulačić, Božo Milković, Stanislav Sočivica, and Counts Franjo and Juraj Posedarski.[73][74] Divided by religion, the Mitrović-Janković family were the leaders of Orthodox Morlachs, while the Smiljanić family were leaders of Catholic Morlachs.[73]

After the dissolution of the Republic of Venice in 1797, and loss of power in Dalmatia, the term Morlach would disappear from use.

Legacy

[edit]During the time of Enlightenment and Romanticism, Morlachs were seen as the "model of primitive Slavdom",[75] and the "spirits of pastoral Arcadia Morlacchia".[76] They attracted the attention of travel writers like 17th-century Jacob Spon and Sir George Wheler,[13][77] and 18th-century writers Johann Gottfried Herder and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who labeled their poems as "Morlackisch".[78][79] In 1793, at the carnival in Venice, a play about Morlachs, Gli Antichi Slavi ("antique Slavs"), was performed, and in 1802 it was reconceived as a ballet Le Nozze dei Morlacchi.[79] At the beginning of the 20th century, still seen as relics from the primitive past and a byword for barbarous people, they may have inspired science fiction novelist H. G. Wells in his depiction of the fictional Morlocks.[17] Thomas Graham Jackson described Morlach women as half-savages wearing "embroidered leggings thet give them the appearance of Indian squaws".[80] In the 20th century, Alice Lee Moqué, as did many other women travelers, in her 1914 travelogue Delightful Dalmatia emphasized the "barbaric gorgeousness" of the sight of Morlach women and men in their folk costumes, which "made Zara's Piazza look like a stage setting", and regretted the coming of new civilization.[80]

In the Balkans, the term became derogatory, indicating people from the mountains and backward people, and became disliked by the Morlachs themselves.[81][82]

Italian cheese Morlacco, also named as Morlak, Morlach, Burlach, or Burlacco, was named after Morlach herders and woodsmen who lived and made it in the region of Monte Grappa.[83][84][85] "Morlacchi" remains attested as an Italian family name.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Morlacchi

- Vlachs in the history of Croatia

- Statuta Valachorum

- Morlachs (Venetian irregulars)

- Vlachs (social class)

Annotations

[edit]- ^ The linguistic assimilation didn't entirely erase Romanian words, the evidence are toponims, and anthroponyms (personal names) with specific Romanian or Slavic words roots and surname ending suffixes "-ul", "-ol", "-or", "-at", "-ar", "-as", "-an", "-man", "-er", "-et", "-ez", after Slavicization often accompanied with ending suffixes "-ić", "-vić", "-ović".[44][45][46]

- ^ That the pastoral way of life was specific for Vlachs is seen in the third chapter of eight book in Alexiad, 12th-century work by Anna Komnene, where along Bulgars are mentioned tribes who live a nomadic life usually called Vlachs.[48] The term "Vlach" was found in many medieval documents, often mentioned alongside other ethnonyms, thus, Zef Mirdita claims that this was more an ethnic than just a social-professional category.[48] Although the term was used for both an ethnic group and pastoralists, P. S. Nasturel emphasized that there existed other general expressions for pastors.[48]

- ^ The "Vlach" or "Romanian" traditional system of counting sheep in pairs do (two), pato (four), šasto (six), šopći (eight), zeći (ten) has been preserved in some mountainous regions of Dalmatian Zagora, Bukovica, Velebit, and Ćićarija.[20][52][53]

- ^ "Vlachs", referring to pastoralists, since the 16th century was a common name for Serbs in the Ottoman Empire and later.[64] Tihomir Đorđević points to the already known fact that the name "Vlach" didn't only refer to genuine Vlachs or Serbs but also to cattle breeders in general.[64] In the work About the Vlachs from 1806, Metropolitan Stevan Stratimirović states that Roman Catholics from Croatia and Slavonia scornfully used the name "Vlach" for "the Slovenians (Slavs) and Serbs, who are of our, Eastern confession (Orthodoxy)", and that "the Turks in Bosnia and Serbia also call every Bosnian or Serbian Christian a Vlach" (T. Đorđević, 1984:110).[64]

- ^ The head leaders in Venice, Ottoman and local Slavic documents were titled as capo, capo direttore, capo principale de Morlachi (J. Mitrović), governatnor delli Morlachi (S. Sorić), governator principale (I. Smiljanić), governator (Š. Bortulačić), gospodin serdar s vojvodami or lo dichiariamo serdar; serdar, and harambaša.[73]

References

[edit]- ^ Davor Dukić; (2003) Contemporary Wars in the Dalmatian Literary Culture of the 17th and 18th Centuries p.132; Journal of Ethnology and Folklore Research (0547–2504) 40 [1]

- ^ Cosma 2011, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d e Caciur 2020, p. 30.

- ^ Mirdita 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Mirdita 2001, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Poghirc, Cicerone (1989). "Romanisation linguistique et culturelle dans les Balkans. Survivance et évolution" [Linguistic and cultural Romanization in the Balkans. Survival and evolution]. Les Aroumains [The Aromanians]. Paris: INALCO. p. 23.

- ^ Cosma 2011, p. 124.

- ^ Skok, Petar (1972). Etimologijski rječnik hrvatskoga ili srpskoga jezika [Etymological dictionary of the Croatian or Serbian language]. Vol. II. Zagreb: Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts. pp. 392–393.

- ^ Caciur 2020, p. 31.

- ^ Wolff 2002, p. 127.

- ^ Bracewell, Catherine Wendy (2011). The Uskoks of Senj: Piracy, Banditry, and Holy War in the Sixteenth-Century Adriatic. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. pp. 17–22. ISBN 9780801477096.

- ^ Wolff 2002, pp. 13, 127–128.

- ^ a b Wolff 2002, p. 128.

- ^ Dana Caciur; (2016) Considerations Regarding the Status of the Morlachs from the Trogir's Hinterland at the Middle of the 16th Century: Being Subjects of the Ottoman Empire and Land Tenants of the Venetian Republic, p. 97; Res Historica, [2]

- ^ Wolff 2002, p. 126; Brookes, Richard (1812). The general gazetteer or compendious geographical dictionary (Morlachia). F.C. and J. Rivington. p. 501.

- ^ Naimark & Case 2003, p. 40.

- ^ a b Wolff 2002, p. 348.

- ^ a b c Beller & Leerssen 2007, p. 235.

- ^ Lovrić 1776, p. 170–181.

- ^ a b c d Vince-Pallua 1992.

- ^ Lovrić 1776, p. 174: Ciò, che non ànno fatto i nostri maggiori, neppur noi vogliam fare.

- ^ Lovrić 1776, p. 170-181.

- ^ Fine 2006, p. 360.

- ^ Fine 2006, p. 356.

- ^ Fine 2006, p. 361.

- ^ Narodna umjetnost. Vol. 34. Institut za narodnu umjetnost. 1997. p. 83.

"It is usual that there is perfect disharmony between the Latin and the Greek religions; neither of the clergymen do not hesitate to sow it: each side tells thousands of scandalous stories about the other" (Fortis 1984:45)

- ^ Christopher Catherwood, Making War In The Name Of God, Kensington Publishing Corp., 1 2008, P. 141.

- ^ MILE BOGOVIć Katolička crkva i pravoslavlje u dalmaciji za vrijeme mletačke vladavine, 1993. (The Catholic Church and Orthodoxy in Dalmatia during the Venetian rule) https://docplayer.it/68017892-Katolicka-crkva-i-pravoslavlje.html #page= 4–5

- ^ Larry Wolff, Rise and fall of Morlachismo. In: Norman M. Naimark, Holly Case, Stanford University Press, Yugoslavia and Its Historians: Understanding the Balkan Wars of the 1990s, ISBN 978-0804745949 p. 44.

- ^ Larry Wolff, Rise and fall of Morlachismo. In: Norman M. Naimark, Holly Case, Stanford University Press, Yugoslavia and Its Historians: Understanding the Balkan Wars of the 1990s, ISBN 978-0804745949 p. 41.

- ^ Milić Brett, Branislava (2014). Imagining the Morlacchi in Fortis and Goldoni (PhD). University of Alberta. pp. 1–213. doi:10.7939/R3MM45.

- ^ Spicijarić Paškvan, Nina (28 June 2018). "Vlachs from the Island Krk in the Primary Historical and Literature Sources". ResearchGate. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 10, 11: Et insuper mittemus specialem nuntium.... Gregorio condam Curiaci Corbavie,.... pro bono et conservatione dicte domine (Vedislave) et comitis Johannis,....; nec non pro restitutione Morolacorum, qui sibi dicuntur detineri per comitem Gregorium...; Exponat quoque idem noster nuncius Gregorio comiti predicto quod intelleximus, quod contra voluntatem ipsius comitis Johannis nepotis sui detinet catunos duos Morolacorum.... Quare dilectionem suam... reget, quatenus si quos Morolacos ipsius habet, placeat illos sibi plenarie restitui facere...

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 10.

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 14-17.

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 11:Detractis modiis XII. milie salis predicti quolibet anno que remaneant in Jadra pro usu Jadre et districtu, et pro exportatione solita fi eri per Morlachos et alios per terram tantum....

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 12:quedam particula gentis Morlachorum ipsius domini nostri regis... tentoria (tents), animalia seu pecudes (sheep)... ut ipsam particulam gentis Morlachorum de ipsorum territorio repellere... dignaremur (to be repelled from city territory)... quamplures Morlachos... usque ad festum S. Georgii martiris (was allowed to stay until April 24, 1362)..

- ^ L. Margetić (December 2007). "Senjski statut iz godine 1388" [Statute of Senj from 1388] (PDF). Senjski zbornik (in Latin and Croatian). 34 (1). Senj: 63, 77.

§ 161. Item, quod quando Morowlachi exeunt de monte et uadunt uersus gaccham, debent stare per dies duos et totidem noctes super pascuis Senie, et totidem tempore quando reuertuntur ad montem; et si plus stant, incidunt ad penam quingentarum librarum.

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 13Cum rectores Jadre scripserint nostro dominio, quod castrum Ostrovich, quod emimusa Sandalo furatum et acceptum sit per certos Murlachos, quod non est sine infamia nostri dominii....

- ^ Fine 2006, p. 115.

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 208.

- ^ Fine 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 73 (I): "As evidence Vlachs spoke a variation of Romanian language, Pavičić later in the paragraph referred to the Istro-Romanians, and Dalmatian language on island Krk."

- ^ P. Šimunović, F. Maletić (2008). Hrvatski prezimenik (in Croatian). Vol. 1. Zagreb: Golden marketing. pp. 41–42, 100–101.

- ^ Šimunović, Petar (2009). Uvod U Hrvatsko Imenoslovlje (in Croatian). Zagreb: Golden marketing-Tehnička knjiga. pp. 53, 123, 147, 150, 170, 216, 217.

- ^ Božidar Ručević (2011-02-27). "Vlasi u nama svima" (in Croatian). Rodoslovlje.

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 80.

- ^ a b c Zef Mirdita (1995). "Balkanski Vlasi u svijetlu podataka Bizantskih autora". Povijesni prilozi (in Croatian). 14 (14). Zagreb: Croatian History Institute: 65, 66, 27–30.

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 73.

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 89.

- ^ Josip Ribarić (2002). O istarskim dijalektima: razmještaj južnoslavenskih dijalekata na poluotoku Istri s opisom vodičkog govora (in Croatian). Zagreb: Josip Turčinović.

- ^ Mirjana Trošelj (2011). "Mitske predaje i legende južnovelebitskog Podgorja" [Mythical Traditions and Legends from Podgorje in southern Velebit]. Studia Mythologica Slavica (in Croatian). 14. Ljubljana: Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts: 346.

- ^ Tono Vinšćak (June 1989). "Kuda idu "horvatski nomadi"". Studia ethnologica Croatica (in Croatian). 1 (1). Zagreb: University of Zagreb: 9.

- ^ Andreose, Alvise (2016). "Sullo "stato di salute" delle varietà romene all'alba del nuovo millennio". Lengas. Revue de sociolinguistique (in Italian). 79 (79). doi:10.4000/lengas.1107.

- ^ a b Carlo de Franceschi (1879). L'Istria: note storiche (in Italian). G. Coana (Harvard University). pp. 355–371.

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 14, 207: Jesu prišli tužiti se na Vlahov, kojih jesmo mi postavili u konfi ni od rečenoga kaštel Mušća (Omišalj) na Kras, kadi se zove v Orlec imenujući Murlakov sudca Gerga Bodolića i sudca Vida Merkovića (...) Darovasmo crikvi sv. Marije na Crikvenici Vlaha, po imenu Mikulu, ki Vlah budući va to vrieme naš osobojni, koga mi dasmo crikvi sv. Marije na Crikvenici sa svu ovu službu, ku je on nam služil budno na našej službi.

- ^ Spicijarić Paškvan, Nina; (2014) Vlasi i krčki Vlasi u literaturi i povijesnim izvorima (Vlachs from the Island Krk in the Primary Historical and Literature Sources) p. 349; Studii şi cercetări – Actele Simpozionului Banat – istorie şi multiculturalitate, [3]

- ^ Mužić 2010, p. 76-79, 87-88.

- ^ Juran 2014, p. 130.

- ^ Juran 2014, p. 131.

- ^ Juran 2014, p. 150.

- ^ Suppan & Graf 2010, p. 55-57.

- ^ Stoianovich, Traian (1992). Balkan Worlds: The First and Last Europe. Armonk: Routledge. p. 152. ISBN 9781563240324.

- ^ a b c Gavrilović, Danijela (2003). "Elements of ethnic identification of the Serbs" (PDF). Facta Universitatis, Series: Philosophy, Sociology, Psychology and History. 2 (10).

- ^ Suppan & Graf 2010, p. 52, 59.

- ^ Kostrenčić, Marko; Krleža, Miroslav, eds. (1961). Enciklopedija Leksikografskog zavoda: Majmonid-Pérez. Zagreb: Jugoslavenski leksikografski zavod. p. 268.

- ^ Juran 2015, p. 47.

- ^ Juran 2015, p. 48.

- ^ a b Gunther Erich Rothenberg (1960). The Austrian military border in Croatia, 1522–1747. University of Illinois Press. p. 50.

- ^ Fine 2006, p. 218.

- ^ Roksandić, Drago (2004). Etnos, konfesija, tolerancija (Priručnik o vojnim krajinama u Dalmaciji iz 1783. godine) (PDF) (in Croatian). Zagreb: SKD Prosvjeta. pp. 11–41.

- ^ Milan Ivanišević (2009). "Izvori za prva desetljeća novoga Vranjica i Solina". Tusculum (in Croatian). 2 (1 September). Solin: 98.

- ^ a b c Sučević, Branko (1952). "Ocjene i prikazi: Boško Desnica, Istorija kotarski uskoka" (PDF). Historijski zbornik. V (1–2). Zagreb: Povijesno društvo Hrvatske: 138–145.

- ^ Roksandić 2003, pp. 140, 141, 151, 169.

- ^ Wolff 2002, p. 13.

- ^ Naimark & Case 2003, p. 41.

- ^ Wendy Bracewell; Alex Drace-Francis (2008). Under Eastern Eyes: A Comparative Introduction to East European Travel Writing on Europe. Central European University Press. pp. 154–157. ISBN 978-9639776111.

- ^ Wolff 2002, p. 190.

- ^ a b Naimark & Case 2003, p. 42.

- ^ a b Naimark & Case 2003, p. 47.

- ^ Henry Baerlein (1922). The Birth of Yugoslavia (Complete). Library of Alexandria. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-1-4655-5007-1.

- ^ Naimark & Case 2003, p. 46.

- ^ "Formaggio Morlacco" (PDF). venetoagricoltura.org (in Italian). Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ "Morlacco del Grappa". venetoformaggi.it (in Italian). Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ "Grappa Mountain Morlacco". fondazioneslowfood.com. Slow Food. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

Sources

[edit]- Primary sources

- Fortis, Alberto (1778). Travels Into Dalmatia: Containing General Observations on the Natural History of that Country and the Neighboring Islands; the Natural Productions, Arts, Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants. London: J. Robson.

- Lovrić, Ivan (1776). Osservazioni sopra diversi pezzi del Viaggio in Dalmazia del signor abate Alberto Fortis coll'aggiunta della Vita di Soçivizça (in Italian). Venice: Presso Francesco Sansoni.

- Books

- Beller, Manfred; Leerssen, Joseph Theodoor (2007). Imagology: The Cultural Construction and Literary Representation of National Characters. Rodopi. ISBN 978-9042023178.

- Cosma, Ela (2011). "Vlahii Negri. Silviu Dragomir despre identitatea morlacilor" [Black Vlachs. Silviu Dragomir about the identity of the Morlachs]. In Pop, Ion-Aurel; Şipoş, Sorin (eds.). Silviu Dragomir – 120 de ani de la naştere [Silviu Dragomir – 120 years anniversary] (PDF). Oradea: University of Oradea. pp. 107–128.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (2006). When ethnicity did not matter in the Balkans. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472025600.

- Mužić, Ivan (2010). Vlasi u starijoj hrvatskoj historiografiji (PDF) (in Croatian). Split: Muzej hrvatskih arheoloških spomenika. ISBN 978-953-6803-25-5.

- Naimark, Norman M.; Case, Holly (2003). Yugoslavia and Its Historians: Understanding the Balkan Wars of the 1990s. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4594-9.

- Roksandić, Drago (2003). Triplex Confinium, Ili O Granicama I Regijama Hrvatske Povijesti 1500–1800 (PDF) (in Croatian). Zagreb: Barbat. pp. 140, 141, 151, 169.

- Suppan, Arnold; Graf, Maximilian (2010). From the Austrian Empire to the Communist East Central Europe. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-643-50235-3.

- Wolff, Larry (2002). Venice and the Slavs: The Discovery of Dalmatia in the Age of Enlightenmen. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804739463.

- Journals

- Mirdita, Zef (2001). "Tko su Maurovlasi odnosno Nigri Latini u "Ljetopisu popa Dukljanina"" [Who are the Maurovlachs or Nigri Latini in the "Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja"]. Croatica Christiana Periodica (in Croatian). 47 (47). Zagreb: 17–27.

- Caciur, Dana (2020). "(Re)searching the Morlachs and the Uskoks: The Challenges of Writing about Marginal People from the Border Region of Dalmatia (Sixteenth Century)". Cromohs - Cyber Review of Modern Historiography. 23: 28–43. doi:10.36253/cromohs-12193. ISSN 1123-7023.

- Juran, Kristijan (2014). "Doseljavanje Morlaka u opustjela sela šibenske Zagore u 16. stoljeću" [The settlement of Morlachs in the deserted villages of the Šibenik hinterland in the 16th century]. Povijesni prilozi (in Croatian). 46.

- Juran, Kristijan (2015). "Morlaci u Šibeniku između Ciparskoga i Kandijskog rata (1570. – 1645.)" [Morlachs in Šibenik between the Cypriot and Cretan Wars (1570-1645)]. Povijesni prilozi (in Croatian). 49.

- Vince-Pallua, Jelka (1992). "Tragom vlaških elemenata kod Morlaka srednjodalmatinskog zaleđa". Ethnologica Dalmatica. 1 (1). Zagreb: University of Zagreb: 137–145.

External links

[edit]- "Morlaci". Croatian Encyclopaedia. 2011.

- Morlachs

- Eastern Romance peoples in Croatia

- Eastern Romance people

- Historical ethnic groups of Europe

- Republic of Venice people

- South Slavic history

- History of Dalmatia

- Military Frontier

- Combat occupations

- 16th century in Croatia

- 17th century in Croatia

- Cretan War (1645–1669)

- Venetian period in the history of Croatia

- Communities in medieval Bosnia