Sindh

Sindh

| |

|---|---|

| Province of Sindh | |

|

| |

| Etymology: Sind | |

| Nickname(s): Mehran (Gateway), Bab-ul-Islam (Gateway of Islam) | |

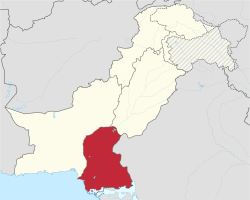

Location of Sindh in Pakistan | |

| Coordinates: 26°21′N 68°51′E / 26.350°N 68.850°E | |

| Country | |

| Established | 1 July 1972 |

| Before was | Part of West Pakistan |

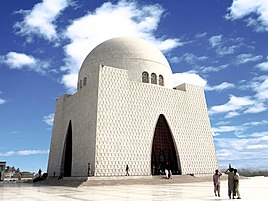

| Capital and largest city | Karachi |

| Administrative Divisions | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Self-governing province subject to the federal government |

| • Body | Government of Sindh |

| • Governor | Kamran Tessori |

| • Chief Minister | Murad Ali Shah |

| • Chief Secretary | Dr Fakhre Alam (BPS-22 PAS) |

| • Legislature | Provincial Assembly |

| • High Court | Sindh High Court |

| Area | |

| • Total | 140,914 km2 (54,407 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 3rd |

| Elevation | 173 m (568 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 55,696,147 |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| • Density | 395/km2 (1,020/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Sindhi |

| GDP (nominal) | |

| • Total | $86 billion (2nd)[a] |

| • Per Capita | $1,997 (3rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | |

| • Total | $345 billion (2nd)[a] |

| • Per Capita | $7,209 (3rd) |

| Time zone | UTC+05:00 (PKT) |

| ISO 3166 code | PK-SD |

| Languages | |

| Notable sports teams | Sindh cricket team Karachi Kings Karachi United Hyderabad Hawks Karachi Dolphins Karachi Zebras |

| HDI (2021) | 0.517

Low |

| Literacy rate (2020) | 61.8% |

| Seats in National Assembly | 75 |

| Seats in Provincial Assembly | 168[5] |

| Divisions | 7 |

| Districts | 30 |

| Tehsils | 138 |

| Union Councils | 1108[6] |

| Website | sindh.gov.pk |

| Part of a series on |

| Sindhis |

|---|

|

Sindh portal |

Sindh (/ˈsɪnd/ SIND; Sindhi: سِنْڌ; Urdu: سِنْدھ, pronounced [sɪndʱə]; abbr. SD, historically romanized as Sind) is a province of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province by population after Punjab. It is bordered by the Pakistani provinces of Balochistan to the west and north-west and Punjab to the north. It shares an International border with the Indian states of Gujarat and Rajasthan to the east; it is also bounded by the Arabian Sea to the south. Sindh's landscape consists mostly of alluvial plains flanking the Indus River, the Thar Desert of Sindh in the eastern portion of the province along the international border with India, and the Kirthar Mountains in the western portion of the province.

The economy of Sindh is the second largest in Pakistan after the province of Punjab; its provincial capital Karachi is the most populous city in the country as well as its main financial hub. Sindh is home to a large portion of Pakistan's industrial sector and contains two of the country's busiest commercial seaports: Port Qasim and the Port of Karachi. The remainder of Sindh consists of an agriculture-based economy and produces fruits, consumer items and vegetables for other parts of the country.[7][8][9]

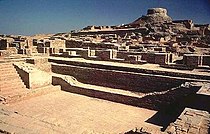

Sindh is sometimes referred to as the Bab-ul Islam (transl. 'Gateway of Islam'), as it was one of the first regions of the Indian subcontinent to fall under Islamic rule.[10][11] The province is well known for its distinct culture, which is strongly influenced by Sufist Islam, an important marker of Sindhi identity for both Hindus and Muslims.[12] Sindh is prominent for its history during the Bronze Age under the Indus Valley civilization, and is home to two UNESCO-designated World Heritage Sites: the Makli Necropolis and Mohenjo-daro.[13]

Etymology

The Greeks who conquered Sindh in 325 BCE under the command of Alexander the Great referred to the Indus River as Indós, hence the modern Indus. The ancient Iranians referred to everything east of the river Indus as hind.[14][15] The word Sindh is a Persian derivative of the Sanskrit term Sindhu, meaning "river," a reference to the Indus River.[16]

Southworth suggests that the name Sindhu is in turn derived from Cintu, a Dravidian word for date palm, a tree commonly found in Sindh.[17][18]

The previous spelling Sind (from the Perso-Arabic سند) was discontinued in 1988 by an amendment passed in the Sindh Assembly.[19]

History

Ancient era

Sindh and surrounding areas contain the ruins of the Indus Valley Civilization. There are remnants of thousand-year-old cities and structures, with a notable example in Sindh being that of Mohenjo Daro. Built around 2500 BCE, it was one of the largest settlements of the ancient Indus civilization, with features such as standardized bricks, street grids, and covered sewerage systems.[20][21] It was one of the world's earliest major cities, contemporaneous with the civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Minoan Crete, and Caral-Supe. Mohenjo-daro was abandoned in the 19th century BCE as the Indus Valley Civilization declined, and the site was not rediscovered until the 1920s. Significant excavation has since been conducted at the site of the city, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980.[22] The site is currently threatened by erosion and improper restoration.[23] A gradual drying of the region during the 3rd millennium BCE may have been the initial stimulus for its urbanisation.[24] Eventually it also reduced the water supply enough to cause the civilisation's demise and to disperse its population to the east.[b]

During the Bronze Age, the territory of Sindh was known as Sindhu-Sauvīra, covering the lower Indus Valley,[25] with its southern border being the Indian Ocean and its northern border being the Pañjāb around Multān.[26] The capital of Sindhu-Sauvīra was named Roruka and Vītabhaya or Vītībhaya, and corresponds to the mediaeval Arohṛ and the modern-day Rohṛī.[26][27][28] The Achaemenids conquered the region and established the satrapy of Hindush. The territory may have corresponded to the area covering the lower and central Indus basin (present day Sindh and the southern Punjab regions of Pakistan).[29] Alternatively, some authors consider that Hindush may have been located in the Punjab area.[30] These areas remained under Persian control until the invasion by Alexander.[31]

Alexander conquered parts of Sindh after Punjab for few years and appointed his general Peithon as governor. He constructed a harbour at the city of Patala in Sindh.[32][33] Chandragupta Maurya fought Alexander's successor in the east, Seleucus I Nicator, when the latter invaded. In a peace treaty, Seleucus ceded all territories west of the Indus River and offered a marriage, including a portion of Bactria, while Chandragupta granted Seleucus 500 elephants.[34]

Following a century of Mauryan rule which ended by 180 BCE, the region came under the Indo-Greeks, followed by the Indo Scythians, who ruled with their capital at Minnagara.[35] Later on, Sasanian rulers from the reign of Shapur I claimed control of the Sindh area in their inscriptions, known as Hind.[36][37]

The local Rai dynasty emerged from Sindh and reigned for a period of 144 years, concurrent with the Huna invasions of North India.[38] Aror was noted to be the capital.[38][39] The Brahmin dynasty of Sindh succeeded the Rai dynasty.[40][41][42][43] Most of the information about its existence comes from the Chach Nama, a historical account of the Chach-Brahmin dynasty.[44] After the empire's fall in 712, though the empire had ended, its dynasty's members administered parts of Sindh under the Umayyad Caliphate's Caliphal province of Sind.[45]

Medieval era

After the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, the Arab expansion towards the east reached the Sindh region beyond Persia.[46] The connection between the Sindh and Islam was established by the initial Muslim invasions during the Rashidun Caliphate. Al-Hakim ibn Jabalah al-Abdi, who attacked Makran in the year 649 CE, was an early partisan of Ali ibn Abu Talib.[47] During the caliphate of Ali, many Jats of Sindh had come under the influence of Shi'ism[48] and some even participated in the Battle of Camel and died fighting for Ali.[47] Under the Umayyads (661–750 CE), many Shias sought asylum in the region of Sindh, to live in relative peace in the remote area. Ziyad Hindi is one of those refugees.[49] The first clash with the Hindu kings of Sindh took place in 636 (15 A.H.) under Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab with the governor of Bahrain, Uthman ibn Abu-al-Aas, dispatching naval expeditions against Thane and Bharuch and Debal.[50] Al-Baladhuri states they were victorious at Debal but doesn't mention the results of other two raids. However, the Chach Nama states that the raid of Debal was defeated and its governor killed the leader of the raids.[51] These raids were thought to be triggered by a later pirate attack on Umayyad ships.[52] Baladhuri adds that this stopped any more incursions until the reign of Uthman.[53]

In 712, Mohammed Bin Qasim defeated the Brahmin dynasty and annexed it to the Umayyad Caliphate. This marked the beginning of Islam in the Indian subcontinent. The Habbari dynasty ruled much of Greater Sindh, as a semi-independent emirate from 854 to 1024. Beginning with the rule of 'Umar bin Abdul Aziz al-Habbari in 854 CE, the region became semi-independent from the Abbasid Caliphate in 861, while continuing to nominally pledge allegiance to the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad.[54][55] The Habbaris ruled Sindh until they were defeated by Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi in 1026, who then went on to destroy the old Habbari capital of Mansura, and annex the region to the Ghaznavid Empire, thereby ending Arab rule of Sindh.[56][57]

The Soomra dynasty was a local Sindhi Muslim dynasty that ruled between early 11th century and the 14th century.[58][59][60] Later chroniclers like Ali ibn al-Athir (c. late 12th c.) and Ibn Khaldun (c. late 14th c.) attributed the fall of Habbarids to Mahmud of Ghazni, lending credence to the argument of Hafif being the last Habbarid.[61] The Soomras appear to have established themselves as a regional power in this power vacuum.[61][62] The Ghurids and Ghaznavids continued to rule parts of Sindh, across the eleventh and early twelfth century, alongside Soomrus.[61] The precise delineations are not yet known but Sommrus were probably centered in lower Sindh.[61] Some of them were adherents of Isma'ilism.[62] One of their kings Shimuddin Chamisar had submitted to Iltutmish, the Sultan of Delhi, and was allowed to continue on as a vassal.[63]

The Sammas overthrew the Soomras soon after 1335 and established the Sindh Sultanate. The last Soomra ruler took shelter with the governor of Gujarat, under the protection of Muhammad bin Tughluq, the sultan of Delhi.[65][66][67] Mohammad bin Tughlaq made an expedition against Sindh in 1351 and died at Sondha, possibly in an attempt to restore the Soomras. With this, the Sammas became independent. The next sultan, Firuz Shah Tughlaq attacked Sindh in 1365 and 1367, unsuccessfully, but with reinforcements from Delhi he later obtained Banbhiniyo's surrender. For a period the Sammas were therefore subject to Delhi again. Later, as the Sultanate of Delhi collapsed they became fully independent.[68] Jam Unar was the founder of Samma dynasty mentioned by Ibn Battuta.[68] The Samma civilization contributed significantly to the evolution of the Indo-Islamic architectural style. Thatta is famous for its necropolis, which covers 10 square km on the Makli Hill.[69] It has left its mark in Sindh with magnificent structures including the Makli Necropolis of its royals in Thatta.[70][71] They were later overthrown by the Turkic Arghuns in the late 15th century.[72][73]

Modern era

In the late 16th century, Sindh was brought into the Mughal Empire by Akbar, himself born in the Rajputana kingdom in Umerkot in Sindh.[74][75] Mughal rule from their provincial capital of Thatta was to last in lower Sindh until the early 18th century, while upper Sindh was ruled by the indigenous Kalhora dynasty holding power, consolidating their rule from their capital of Khudabad, before shifting to Hyderabad from 1768 onwards.[76][77][78]

The Talpurs succeeded the Kalhoras and four branches of the dynasty were established.[79] One ruled lower Sindh from the city of Hyderabad, another ruled over upper Sindh from the city of Khairpur, a third ruled around the eastern city of Mirpur Khas, and a fourth was based in Tando Muhammad Khan. They were ethnically Baloch,[80] and for most of their rule, they were subordinate to the Durrani Empire and were forced to pay tribute to them.[81][82]

They ruled from 1783, until 1843, when they were in turn defeated by the British at the Battle of Miani and Battle of Dubbo.[83] The northern Khairpur branch of the Talpur dynasty, however, continued to maintain a degree of sovereignty during British rule as the princely state of Khairpur,[80] whose ruler elected to join the new Dominion of Pakistan in October 1947 as an autonomous region, before being fully amalgamated into West Pakistan in 1955.

British Raj

The British conquered Sindh in 1843. General Charles Napier is said to have reported victory to the Governor General with a one-word telegram, namely "Peccavi" – or "I have sinned" (Latin).[84] The British had two objectives in their rule of Sindh: the consolidation of British rule and the use of Sindh as a market for British products and a source of revenue and raw materials. With the appropriate infrastructure in place, the British hoped to utilise Sindh for its economic potential.[85] The British incorporated Sindh, some years later after annexing it, into the Bombay Presidency. Distance from the provincial capital, Bombay, led to grievances that Sindh was neglected in contrast to other parts of the Presidency. The merger of Sindh into Punjab province was considered from time to time but was turned down because of British disagreement and Sindhi opposition, both from Muslims and Hindus, to being annexed to Punjab.[85]

Later, desire for a separate administrative status for Sindh grew. At the annual session of the Indian National Congress in 1913, a Sindhi Hindu put forward the demand for Sindh's separation from the Bombay Presidency on the grounds of Sindh's unique cultural character. This reflected the desire of Sindh's predominantly Hindu commercial class to free itself from competing with the more powerful Bombay's business interests.[85] Meanwhile, Sindhi politics was characterised in the 1920s by the growing importance of Karachi and the Khilafat Movement.[86] A number of Sindhi pirs, descendants of Sufi saints who had proselytised in Sindh, joined the Khilafat Movement, which propagated the protection of the Ottoman Caliphate, and those pirs who did not join the movement found a decline in their following.[87] The pirs generated huge support for the Khilafat cause in Sindh.[88] Sindh came to be at the forefront of the Khilafat Movement.[89]

Although Sindh had a cleaner record of communal harmony than other parts of India, the province's Muslim elite and emerging Muslim middle class demanded separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency as a safeguard for their own interests. In this campaign, local Sindhi Muslims identified 'Hindu' with Bombay instead of Sindh. Sindhi Hindus were seen as representing the interests of Bombay instead of the majority of Sindhi Muslims. Sindhi Hindus, for the most part, opposed the separation of Sindh from Bombay.[85] Although Sindh had a culture of religious syncretism, communal harmony and tolerance due to Sindh's strong Sufi culture in which both Sindhi Muslims and Sindhi Hindus partook,[90] both the Muslim landed elite, waderas, and the Hindu commercial elements, banias, collaborated in oppressing the predominantly Muslim peasantry of Sindh who were economically exploited.[91] Sindhi Muslims eventually demanded the separation of Sindh from the Bombay Presidency, a move opposed by Sindhi Hindus.[88][92][93]

In Sindh's first provincial election after its separation from Bombay in 1936, economic interests were an essential factor of politics informed by religious and cultural issues.[94] Due to British policies, much land in Sindh was transferred from Muslim to Hindu hands over the decades.[95] Religious tensions rose in Sindh over the Sukkur Manzilgah issue where Muslims and Hindus disputed over an abandoned mosque in proximity to an area sacred to Hindus. The Sindh Muslim League exploited the issue and agitated for the return of the mosque to Muslims. Consequentially, a thousand members of the Muslim League were imprisoned. Eventually, due to panic the government restored the mosque to Muslims.[94] The separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency triggered Sindhi Muslim nationalists to support the Pakistan Movement. Even while the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province were ruled by parties hostile to the Muslim League, Sindh remained loyal to Jinnah.[96] Although the prominent Sindhi Muslim nationalist G. M. Syed left the All India Muslim League in the mid-1940s and his relationship with Jinnah never improved, the overwhelming majority of Sindhi Muslims supported the creation of Pakistan, seeing in it their deliverance.[86] Sindhi support for the Pakistan Movement arose from the desire of the Sindhi Muslim business class to drive out their Hindu competitors.[97] The Muslim League's rise to becoming the party with the strongest support in Sindh was in large part linked to its winning over of the religious pir families.[98] Although the Muslim League had previously fared poorly in the 1937 elections in Sindh, when local Sindhi Muslim parties won more seats,[98] the Muslim League's cultivation of support from local pirs in 1946 helped it gain a foothold in the province,[99] it didn't take long for the overwhelming majority of Sindhi Muslims to campaign for the creation of Pakistan.[100][101]

Partition (1947)

In 1947, violence did not constitute a major part of the Sindhi partition experience, unlike in Punjab. There were very few incidents of violence on Sindh, in part due to the Sufi-influenced culture of religious tolerance and in part that Sindh was not divided and was instead made part of Pakistan in its entirety. Sindhi Hindus who left generally did so out of a fear of persecution, rather than persecution itself, because of the arrival of Muslim refugees from India. Sindhi Hindus differentiated between the local Sindhi Muslims and the migrant Muslims from India. A large number of Sindhi Hindus travelled to India by sea, to the ports of Bombay, Porbandar, Veraval and Okha.[102]

Demographics

| Demographic Indicators | |

|---|---|

| Urban population | 53.97% |

| Rural population | 46.03% |

| Population growth rate | 2.57% |

| Gender ratio (male per 100 female) | 108.76[103] |

| Economically active population | 22.75% (Old Data) |

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1891 | 2,875,100 | — |

| 1901 | 3,410,223 | +18.6% |

| 1911 | 3,737,223 | +9.6% |

| 1921 | 3,472,508 | −7.1% |

| 1931 | 4,114,253 | +18.5% |

| 1941 | 4,840,795 | +17.7% |

| 1951 | 6,047,748 | +24.9% |

| 1961 | 8,367,065 | +38.4% |

| 1972 | 14,155,909 | +69.2% |

| 1981 | 19,028,666 | +34.4% |

| 1998 | 29,991,161 | +57.6% |

| 2017 | 47,854,510 | +59.6% |

| 2023 | 55,696,147 | +16.4% |

| Source: Census in Pakistan, Census of British Raj[104]: 7 [c][d][e][f][g] | ||

Sindh has the second highest Human Development Index out of all of Pakistan's provinces at 0.628.[109] The 2023 Census of Pakistan indicated a population of 55.7 million.

Religion

Religion in Sindh according to 2023 census

Islam in Sindh has a long history, starting with the capture of Sindh by Muhammad Bin Qasim in 712 CE. Over time, the majority of the population in Sindh converted to Islam, especially in rural areas. Today, Muslims make up 90% of the population, and are more dominant in urban than rural areas. Islam in Sindh has a strong Sufi ethos with numerous Muslim saints and mystics, such as the Sufi poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, having lived in Sindh historically. One popular legend that highlights the strong Sufi presence in Sindh is that 125,000 Sufi saints and mystics are buried on Makli Hill near Thatta.[110] The development of Sufism in Sindh was similar to the development of Sufism in other parts of the Muslim world. In the 16th century two Sufi tareeqat (orders) – Qadria and Naqshbandia – were introduced in Sindh.[111] Sufism continues to play an important role in the daily lives of Sindhis.[112]

In 1941, the last census conducted prior to the partition of India, the total population of Sindh was 4,840,795 out of which 3,462,015 (71.5%) were Muslims, 1,279,530 (26.4%) were Hindus and the remaining were Tribals, Sikhs, Christians, Parsis, Jains, Jews, and Buddhists.[104]: 28 [113]

Sindh also has Pakistan's highest percentage of Hindus overall, accounting for 8.8% of the population, roughly around 4.9 million people,[114] and 13.3% of the province's rural population as per 2023 Pakistani census report. These numbers also include the scheduled caste population, which stands at 1.7% of the total in Sindh (or 3.1% in rural areas),[115] and is believed to have been under-reported, with some community members instead counted under the main Hindu category.[116] Although, Pakistan Hindu Council claimed that there are 6,842,526 Hindus living in Sindh Province covering around 14.29% of the region's population.[117] Umerkot district in the Thar Desert is Pakistan's only Hindu-majority district. The Shri Ramapir Temple in Tandoallahyar whose annual festival is the second largest Hindu pilgrimage in Pakistan is in Sindh.[118] Sindh is also the only province in Pakistan to have a separate law for governing Hindu marriages.[119]

Per community estimates, there are approximately 10,000 Sikhs in Sindh.[120]

| Religious group |

1901[108][g] | 1911[107][f] | 1921[106][e] | 1931[105][d] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Islam |

2,609,337 | 76.52% | 2,822,756 | 75.53% | 2,562,700 | 73.8% | 3,017,377 | 73.34% |

| Hinduism |

787,683 | 23.1% | 877,313 | 23.47% | 876,629 | 25.24% | 1,055,119 | 25.65% |

| Christianity |

7,825 | 0.23% | 10,917 | 0.29% | 11,734 | 0.34% | 15,152 | 0.37% |

| Zoroastrianism |

2,000 | 0.06% | 2,411 | 0.06% | 2,913 | 0.08% | 3,537 | 0.09% |

| Jainism |

921 | 0.03% | 1,349 | 0.04% | 1,534 | 0.04% | 1,144 | 0.03% |

| Judaism |

428 | 0.01% | 595 | 0.02% | 671 | 0.02% | 985 | 0.02% |

| Buddhism |

0 | 0% | 21 | 0.001% | 41 | 0.001% | 53 | 0.001% |

| Sikhism |

— | — | 12,339 | 0.33% | 8,036 | 0.23% | 19,172 | 0.47% |

| Tribal[h] | — | — | 9,224 | 0.25% | 8,186 | 0.24% | 204 | 0% |

| Others | 2,029 | 0.06% | 298 | 0.01% | 64 | 0.002% | 1,510 | 0.04% |

| Total Population | 3,410,223 | 100% | 3,737,223 | 100% | 3,472,508 | 100% | 4,114,253 | 100% |

| Religious group |

1941[104]: 28 [c] | 1951[121]: 22–26 [i] | 1998[122] | 2017[123][114] | 2023[124][125] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Islam |

3,462,015 | 71.52% | 5,535,645 | 91.53% | 27,796,814 | 91.32% | 43,234,107 | 90.34% | 50,126,428 | 90.09% |

| Hinduism |

1,279,530 | 26.43% | 482,560 | 7.98% | 2,280,842 | 7.49% | 4,176,986 | 8.73% | 4,901,407 | 8.81% |

| Tribal | 37,598 | 0.78% | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Sikhism |

32,627 | 0.67% | — | — | — | — | — | — | 5,182 | 0.01% |

| Christianity |

20,304 | 0.42% | 22,601 | 0.37% | 294,885 | 0.97% | 408,301 | 0.85% | 546,968 | 0.98% |

| Zoroastrianism |

3,841 | 0.08% | 5,046 | 0.08% | — | — | — | — | 1,763 | 0.003% |

| Jainism |

3,687 | 0.08% | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Judaism |

1,082 | 0.02% | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Buddhism |

111 | 0.002% | 670 | 0.01% | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ahmadiyya |

— | — | — | — | 43,524 | 0.14% | 21,661 | 0.05% | 18,266 | 0.03% |

| Others | 0 | 0% | 1,226 | 0.02% | 23,828 | 0.08% | 13,455 | 0.03% | 38,395 | 0.07% |

| Total Population | 4,840,795 | 100% | 6,047,748 | 100% | 30,439,893 | 100% | 47,854,510 | 100% | 55,638,409 | 100% |

Languages

According to the 2023 census, the most widely spoken language in the province is Sindhi, the first language of 33,462,299 60% of the population. It is followed by Urdu 12,409,745 (22%), Pashto 2,955,893 (5.3%), Punjabi 2,265,471 (4.1%), Balochi 1,208,147 (2.2%), Saraiki 913,418 (1.6%), and Hindko 830,581 (1.5), Brahui 265,769, Mewati 57,059, Kashmiri 53,249, Balti 27,193, Shina 22,273, Koshistani 14,885, 777 Kalasha and others are 1,151,650,[126] Other minority languages include Kutchi, Gujarati,[127] Aer, Bagri, Bhaya, Brahui, Dhatki, Ghera, Goaria, Gurgula, Jadgali, Jandavra, Jogi, Kabutra, Kachi Koli, Parkari Koli, Wadiyari Koli, Loarki, Marwari, Sansi, and Vaghri.[128]

Karachi city is Sindh's most multiethnic city which hosts most of the province's Urdu-speaking population who form a plurality, along many other groups.[129]

Geography and nature

Sindh is in the western corner of South Asia, bordering the Iranian plateau in the west. Geographically it is the third largest province of Pakistan, stretching about 579 kilometres (360 mi) from north to south and 442 kilometres (275 mi) (extreme) or 281 kilometres (175 mi) (average) from east to west, with an area of 140,915 square kilometres (54,408 sq mi) of Pakistani territory. Sindh is bounded by the Thar Desert to the east, the Kirthar Mountains to the west and the Arabian Sea and Rann of Kutch to the south. In the centre is a fertile plain along the Indus River.

Sindh is divided into three main geographical regions: Siro ("upper country"), aka Upper Sindh, which is above Sehwan; Vicholo ("middle country"), or Middle Sindh, from Sehwan to Hyderabad; and Lāṟu ("sloping, descending country"), or Lower Sindh, mostly consisting of the Indus Delta below Hyderabad.[130]

Flora

The province is mostly arid with scant vegetation except for the irrigated Indus Valley. The dwarf palm, Acacia rupestris (kher), and Tecomella undulata (lohirro) trees are typical of the western hill region. In the Indus valley, the Acacia nilotica (babul) (babbur) is the most dominant and occurs in thick forests along the Indus banks. The Azadirachta indica (neem) (nim), Zizyphys vulgaris (bir) (ber), Tamarix orientalis (jujuba lai) and Capparis aphylla (kirir) are among the more common trees.

Mango, date palms and the more recently introduced banana, guava, orange and chiku are the typical fruit-bearing trees. The coastal strip and the creeks abound in semi-aquatic and aquatic plants and the inshore Indus delta islands have forests of Avicennia tomentosa (timmer) and Ceriops candolleana (chaunir) trees. Water lilies grow in abundance in the numerous lake and ponds, particularly in the lower Sindh region.[citation needed]

Fauna

Among the wild animals, the Sindh ibex (sareh), blackbuck, wild sheep (Urial or gadh) and wild bear are found in the western rocky range. The leopard is now rare and the Asiatic cheetah extinct. The Pirrang (large tiger cat or fishing cat) of the eastern desert region is also disappearing. Deer occur in the lower rocky plains and in the eastern region, as do the Striped hyena (charakh), jackal, fox, porcupine, common gray mongoose and hedgehog. The Sindhi phekari, red lynx or Caracal cat, is found in some areas. Phartho (hog deer) and wild bear occur, particularly in the central inundation belt. There are bats, lizards and reptiles, including the cobra, lundi (viper) and the mysterious Sindh krait of the Thar region, which is supposed to suck the victim's breath in his sleep. Some unusual sightings of Asian cheetah occurred in 2003 near the Balochistan border in Kirthar Mountains. The rare Houbara bustard finds Sindh's warm climate suitable to rest and mate. Unfortunately, it is hunted by locals and foreigners.

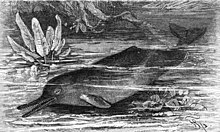

Crocodiles are rare and inhabit only the backwaters of the Indus, eastern Nara channel and Karachi backwater. Besides a large variety of marine fish, the plumbeous dolphin, the beaked dolphin, rorqual or blue whale and skates frequent the seas along the Sindh coast. The Pallo (Sable fish), a marine fish, ascends the Indus annually from February to April to spawn. The Indus river dolphin is among the most endangered species in Pakistan and is found in the part of the Indus river in northern Sindh. Hog deer and wild bear occur, particularly in the central inundation belt.

Although Sindh has a semi arid climate, through its coastal and riverine forests, its huge fresh water lakes and mountains and deserts, Sindh supports a large amount of varied wildlife. Due to the semi-arid climate of Sindh the left out forests support an average population of jackals and snakes. The national parks established by the Government of Pakistan in collaboration with many organizations such as World Wide Fund for Nature and Sindh Wildlife Department support a huge variety of animals and birds. The Kirthar National Park in the Kirthar range spreads over more than 3000 km2 of desert, stunted tree forests and a lake. The KNP supports Sindh ibex, wild sheep (urial) and black bear along with the rare leopard. There are also occasional sightings of The Sindhi phekari, ped lynx or Caracal cat. There is a project to introduce tigers and Asian elephants too in KNP near the huge Hub Dam Lake. Between July and November when the monsoon winds blow onshore from the ocean, giant olive ridley turtles lay their eggs along the seaward side. The turtles are protected species. After the mothers lay and leave them buried under the sands the SWD and WWF officials take the eggs and protect them until they are hatched to keep them from predators.

Climate

Sindh lies in a tropical to subtropical region; it is hot in the summer and mild to warm in winter. Temperatures frequently rise above 46 °C (115 °F) between May and August, and the minimum average temperature of 2 °C (36 °F) occurs during December and January in the northern and higher elevated regions. The annual rainfall averages about seven inches, falling mainly during July and August. The southwest monsoon wind begins in mid-February and continues until the end of September, whereas the cool northerly wind blows during the winter months from October to January.

Sindh lies between the two monsoons—the southwest monsoon from the Indian Ocean and the northeast or retreating monsoon, deflected towards it by the Himalayan mountains—and escapes the influence of both. The region's scarcity of rainfall is compensated by the inundation of the Indus twice a year, caused by the spring and summer melting of Himalayan snow and by rainfall in the monsoon season.

Sindh is divided into three climatic regions: Siro (the upper region, centred on Jacobabad), Wicholo (the middle region, centred on Hyderabad), and Lar (the lower region, centred on Karachi). The thermal equator passes through upper Sindh, where the air is generally very dry. Central Sindh's temperatures are generally lower than those of upper Sindh but higher than those of lower Sindh. Dry hot days and cool nights are typical during the summer. Central Sindh's maximum temperature typically reaches 43–44 °C (109–111 °F). Lower Sindh has a damper and humid maritime climate affected by the southwestern winds in summer and northeastern winds in winter, with lower rainfall than Central Sindh. Lower Sindh's maximum temperature reaches about 35–38 °C (95–100 °F). In the Kirthar range at 1,800 m (5,900 ft) and higher at Gorakh Hill and other peaks in Dadu District, temperatures near freezing have been recorded and brief snowfall is received in the winters.

Major cities

| List of major cities in Sindh | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | City | District(s) | Population | Image |

| 1 | Karachi | Nazimabad, Orangi, Gulshan, Korangi, Malir, Keamari, Karachi | 21,910,352[132] |

|

| 2 | Hyderabad | Hyderabad | 1,732,693 |

|

| 3 | Sukkur | Sukkur | 499,900 |

|

| 4 | Larkana | Larkana | 490,508 |

|

| 5 | Benazirabad[132] | Shaheed Benazirabad | 279,689 |

|

| 6 | Kotri | Jamshoro | 259,358 |

|

| 7 | Mirpur Khas | Mirpur Khas | 233,916 |

|

| 8 | Shikarpur | Shikarpur | 195,437 |  |

| 9 | Jacobabad | Jacobabad | 191,076 |

|

| 10 | Khairpur | Khairpur | 183,181 |

|

| Source: Pakistan Census 2017[133] | ||||

| This is a list of city proper populations and does not indicate metro populations. | ||||

Government

Sindh province

| Provincial animal | Sindh ibex |  |

|---|---|---|

| Provincial bird | Black partridge |  |

| Provincial tree | Neem Tree |  |

The Provincial Assembly of Sindh is a unicameral and consists of 168 seats, of which 5% are reserved for non-Muslims and 17% for women. The provincial capital of Sindh is Karachi. The provincial government is led by Chief Minister who is directly elected by the popular and landslide votes; the Governor serves as a ceremonial representative nominated and appointed by the President of Pakistan. The administrative boss of the province who is in charge of the bureaucracy is the Chief Secretary Sindh, who is appointed by the Prime Minister of Pakistan. Most of the influential Sindhi tribes in the province are involved in Pakistan's politics.

In addition, Sindh's politics leans towards the left-wing and its political culture serves as a dominant place for the left-wing spectrum in the country.[137] The province's trend towards the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and away from the Pakistan Muslim League (N) can be seen in nationwide general elections, in which Sindh is a stronghold of the PPP.[137] The PML(N) has a limited support due to its centre-right agenda.[138]

In metropolitan cities such as Karachi and Hyderabad, the MQM (another party of the left with the support of Muhajirs) has a considerable vote bank and support.[137] Minor leftist parties such as the People's Movement also found support in rural areas of the province.[139]

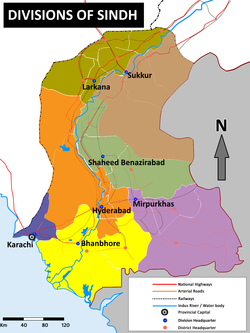

Divisions

In 2008, after the public elections, the new government decided to restore the structure of Divisions of all provinces.[140] In Sindh after the lapse of the Local Governments Bodies term in 2010 the Divisional Commissioners system was to be restored.[141][142][143]

In July 2011, following excessive violence in the city of Karachi and after the political split between the ruling PPP and the majority party in Sindh, the MQM and after the resignation of the MQM Governor of Sindh, PPP and the Government of Sindh decided to restore the commissionerate system in the province. As a consequence, the five divisions of Sindh were restored – namely Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur, Mirpurkhas and Larkana with their respective districts. Subsequently, a new division was added in Sindh, the Nawab Shah/Shaheed Benazirabad division.[144]

Karachi district has been de-merged into its five original constituent districts: Karachi East, Karachi West, Karachi Central, Karachi South and Malir. Recently Korangi has been upgraded to the status of the sixth district of Karachi. These six districts form the Karachi Division now.[145] In 2020, the Kemari District was created after splitting Karachi West District.[146] Currently the Sindh government is planning to divide the Tharparkar district into Tharparkar and Chhachro district.[147]

Districts

| Sr. No. | District | Headquarters | Area (km2) |

Population (in 2017) |

Density (people/km2) |

Division |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Badin | Badin | 6,470 | 1,804,516 | 279 | Hyderabad |

| 2 | Dadu | Dadu | 8,034 | 1,550,266 | 193 | Hyderabad |

| 3 | Ghotki | Ghotki | 6,506 | 1,647,239 | 253 | Sukkur |

| 4 | Hyderabad | Hyderabad | 1,022 | 2,201,079 | 2,155 | Hyderabad |

| 5 | Jacobabad | Jacobabad | 2,771 | 1,006,297 | 363 | Larkana |

| 6 | Jamshoro | Jamshoro | 11,250 | 993,142 | 88 | Hyderabad |

| 7 | Karachi Central | Karachi | 62 | 2,972,639 | 48,336 | Karachi |

| 8 | Kashmore (formerly Kandhkot) | Kashmore | 2,551 | 1,089,169 | 427 | Larkana |

| 9 | Khairpur | Khairpur | 15,925 | 2,405,523 | 151 | Sukkur |

| 10 | Larkana | Larkana | 1,906 | 1,524,391 | 800 | Larkana |

| 11 | Matiari | Matiari | 1,459 | 769,349 | 527 | Hyderabad |

| 12 | Mirpur Khas | Mirpur Khas | 3,319 | 1,505,876 | 454 | Mirpur Khas |

| 13 | Naushahro Feroze | Naushahro Feroze | 2,027 | 1,612,373 | 369 | Shaheed Benazir Abad |

| 14 | Shaheed Benazirabad (formerly Nawabshah) | Nawabshah | 4,618 | 1,612,847 | 349 | Shaheed Benazir Abad |

| 15 | Qambar Shahdadkot | Qambar | 5,599 | 1,341,042 | 240 | Larkana |

| 16 | Sanghar | Sanghar | 10,259 | 2,057,057 | 200 | Shaheed Benazir Abad |

| 17 | Shikarpur | Shikarpur | 2,577 | 1,231,481 | 478 | Larkana |

| 18 | Sukkur | Sukkur | 5,216 | 1,487,903 | 285 | Sukkur |

| 19 | Tando Allahyar | Tando Allahyar | 1,573 | 836,887 | 532 | Hyderabad |

| 20 | Tando Muhammad Khan | Tando Muhammad Khan | 1,814 | 677,228 | 373 | Hyderabad |

| 21 | Tharparkar | Mithi | 19,808 | 1,649,661 | 83 | Mirpur Khas |

| 22 | Thatta | Thatta | 7,705 | 979,817 | 127 | Hyderabad |

| 23 | Umerkot | Umerkot | 5,503 | 1,073,146 | 195 | Mirpur Khas |

| 24 (22) | Sujawal | Sujawal | 8,699 | 781,967 | 90 | Hyderabad |

| 25 (7) | Karachi East | Karachi | 165 | 2,909,921 | 17,625 | Karachi |

| 26 (7) | Karachi South | Karachi | 85 | 1,791,751 | 21,079 | Karachi |

| 27 (7) | Karachi West | Karachi | 630 | 3,914,757 | 6,212 | Karachi |

| 28 (7) | Korangi | Korangi Town | 95 | 2,457,019 | 25,918 | Karachi |

| 29 (7) | Malir | Malir Town | 2,635 | 2,008,901 | 762 | Karachi |

| 30 (7) | Kemari | Karachi | N/A | Karachi |

Lower-level subdivisions

In Sindh, talukas are equivalent to the tehsils used elsewhere in the country, supervisory tapas correspond with the kanungo circles used elsewhere, tapas correspond with the patwar circles used in other provinces, and dehs are equivalent to the mouzas used elsewhere.[148]

Towns and villages

Economy

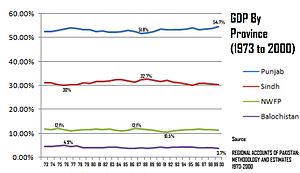

The economy of Sindh is the 2nd largest of all the provinces in Pakistan. Much of Sindh's economy is influenced by the economy of Karachi, the largest city and economic capital of the country. Historically, Sindh's contribution to Pakistan's GDP has been between 30% and 32.7%. Its share in the service sector has ranged from 21% to 27.8% and in the agriculture sector from 21.4% to 27.7%. Performance-wise, its best sector is the manufacturing sector, where its share has ranged from 36.7% to 46.5%.[149] Since 1972, Sindh's GDP has expanded by 3.6 times.[150]

Endowed with coastal access, Sindh is a major centre of economic activity in Pakistan and has a highly diversified economy ranging from heavy industry and finance centred in and around Karachi to a substantial agricultural base along the Indus. Manufacturing includes machine products, cement, plastics, and various other goods.

Agriculture plays an important role in Sindh with cotton, rice, wheat, sugar cane, bananas, and mangoes as the most important crops. The largest and finer quality of rice is produced in Larkano district.[151][152]

Sindh is the richest province in natural resources of gas, petrol, and coal. The Mari Gas field is the biggest producer of natural gas in the country, with companies like Mari Petroleum.[153] Thar coalfield also includes a large lignite deposit.[153]

Education

| Year | Literacy rate |

|---|---|

| 1972 | 60.77 |

| 1981 | 37.5% |

| 1998 | 45.29% |

| 2017 | 54.57%[154] |

The following is a chart of the education market of Sindh estimated by the government in 1998:[155]

| Qualification | Urban | Rural | Total | Enrollment ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | 14,839,862 | 15,600,031 | 30,439,893 | — |

| Below Primary | 1,984,089 | 3,332,166 | 5,316,255 | 100.00 |

| Primary | 3,503,691 | 5,687,771 | 9,191,462 | 82.53 |

| Middle | 3,073,335 | 2,369,644 | 5,442,979 | 52.33 |

| Matriculation | 2,847,769 | 2,227,684 | 5,075,453 | 34.45 |

| Intermediate | 1,473,598 | 1,018,682 | 2,492,280 | 17.78 |

| Diploma, Certificate... | 1,320,747 | 552,241 | 1,872,988 | 9.59 |

| BA, BSc... degrees | 440,743 | 280,800 | 721,543 | 9.07 |

| MA, MSc... degrees | 106,847 | 53,040 | 159,887 | 2.91 |

| Other qualifications | 89,043 | 78,003 | 167,046 | 0.54 |

Major public and private educational institutes in Sindh include:

- Adamjee Government Science College

- Aga Khan University

- APIIT

- Applied Economics Research Centre

- Bahria University

- Baqai Medical University

- Chandka Medical College Larkana

- Cadet College Petaro

- College of Digital Sciences

- College of Physicians & Surgeons Pakistan

- COMMECS Institute of Business and Emerging Sciences

- D. J. Science College

- Dawood University of Engineering & Technology

- Defence Authority Degree College for Men

- Dow International Medical College

- Dow University of Health Sciences

- Fatima Jinnah Dental College

- Federal Urdu University

- GBELS Dourai Mahar Taluka Daur Distt: Shaheed Benazirabad

- Ghulam Muhammad Mahar Medical College Sukkur

- Government College for Men Nazimabad

- Government College Hyderabad

- Government College of Commerce & Economics

- Government College of Technology, Karachi

- Government Degree College Matiari

- Government High School Ranipur

- Government Islamia Science College Sukkur

- Government Muslim Science College Hyderabad

- Government National College (Karachi)

- Greenwich University (Karachi)

- Hamdard University

- Hussain Ebrahim Jamal Research Institute of Chemistry

- Imperial Science College Nawabshah

- Indus Valley Institute of Art and Architecture

- Institute of Business Administration, Karachi

- Institute of Business Administration, Sukkar

- Institute of Business Management

- Institute of Industrial Electronics Engineering

- Institute of Sindhology

- Iqra University

- Islamia Science College (Karachi)

- Isra University Hyderabad

- Jinnah Medical & Dental College

- Jinnah Polytechnic Institute

- Jinnah Post Graduate Medical Centre

- Jinnah University for Women

- KANUPP Institute of Nuclear Power Engineering

- Karachi Institute of Economics and Technology

- Karachi School of Business and Leadership

- Liaquat University of Medical & Health Sciences

- Mehran University of Engineering and Technology

- Mohammad Ali Jinnah University

- National Academy of Performing Arts

- National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences

- National University of Modern Languages

- National University of Sciences and Technology

- NED University of Engineering and Technology

- Ojha Institute of Chest Diseases

- PAF Institute of Aviation Technology

- TES Public School, Daur

- Pakistan Navy Engineering College

- Pakistan Shipowners' College

- Pakistan Steel Cadet College

- Peoples Medical College for Girls Nawabshah

- PIA Training Centre Karachi

- Provincial Institute of Teachers Education Nawabshah

- Public School Hyderabad

- Quaid-e-Awam University of Engineering, Science and Technology, Nawabshah

- Rana Liaquat Ali Khan Government College of Home Economics

- Saint Patrick's College, Karachi

- Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai University

- Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Medical College

- Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology

- Sindh Agriculture University

- Sindh Medical College

- Superior College of Science Hyderabad

- Sindh Muslim Law College

- Sir Syed Government Girls College

- Sir Syed University of Engineering and Technology

- St. Joseph's College

- Sukkur Institute of Science & Technology

- Textile Institute of Pakistan

- University of Karachi

- University of Sindh

- Usman Institute of Technology

- Ziauddin Medical University

Culture

The rich culture, art and architectural landscape of Sindh have fascinated historians. The culture, folktales, art and music of Sindh form a mosaic of human history.[156]

Cultural heritage

The work of Sindhi artisans was sold in ancient markets of Damascus, Baghdad, Basra, Istanbul, Cairo and Samarkand. Referring to the lacquer work on wood locally known as Jandi, T. Posten (an English traveller who visited Sindh in the early 19th century) asserted that the articles of Hala could be compared with exquisite specimens of China. Technological improvements such as the spinning wheel (charkha) and treadle (pai-chah) in the weaver's loom were gradually introduced and the processes of designing, dyeing and printing by block were refined. The refined, lightweight, colourful, washable fabrics from Hala became a luxury for people used to the woollens and linens of the age.[157]

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) such as the World Wildlife Fund, Pakistan, play an important role to promote the culture of Sindh. They provide training to women artisans in Sindh so they get a source of income. They promote their products under the name of "Crafts Forever". Many women in rural Sindh are skilled in the production of caps. Sindhi caps are manufactured commercially on a small scale at New Saeedabad and Hala New. Sindhi people began celebrating Sindhi Topi Day on 6 December 2009, to preserve the historical culture of Sindh by wearing Ajrak and Sindhi topi.[158]

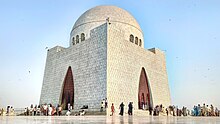

Tourism

Sindh is a province in Pakistan.

The province includes a number of important historical sites. The Indus Valley civilization (IVC) was a Bronze Age civilization (mature period 2600–1900 BCE) which was centred mostly in the Sindh.[159]Sindh has numerous tourist sites with the most prominent being the ruins of Mohenjo-daro near the city of Larkana.[159] Islamic architecture is quite prominent as well as colonial and post-partition sites. Additionally natural sites, like Manchar Lake have increasingly been a source of sustainable tourism in the province.[160]-

Gorakh Hill Station, Dadu

-

Faiz Mahal, Khairpur

-

Ranikot Fort, one of the largest forts in the world Thana Bula Khan, Jamshoro

-

Chaukhandi tombs, Karachi

-

Remains of 9th century Jain temple in Bhodesar, near Nagarparkar

-

Excavated ruins of Mohenjo-daro

-

Karachi Beach

-

Qasim fort, Manora Island Karachi

-

Kot Diji, Khairpur

-

Bakri Waro Lake, Khairpur

-

National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi

-

Kirthar National Park, Thano Bula Khan, Jamshoro

-

Karoonjhar Mountains, Tharparkar

-

Tomb of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, Matiari

-

Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, Sehwan Sharif, Jamshoro

-

Tomb of Mian Noor Muhammad, Benazirabad

CNIC Codes

- Hyderabad Division (41XXX)

- Karachi Division (42101-42501)

- Larkana Division (43XXX)

- Mirpur Khas Division (44XXX)

- Sukkur Division + Shaheed Benazirabad Division (45XXX)

See also

- Arab Sind

- Bagh Prints

- Brahma from Mirpur-Khas

- Debal

- Institute of Sindhology

- List of cities in Sindh by population

- List of cultural heritage sites in Sindh

- List of medical schools in Sindh

- List of districts of Pakistan

- List of Sindhi people

- List of Sindhi tribes

- Mansura, Sindh

- Mohenjo-daro

- Provincial Highways of Sindh

- Sind Division

- Sindh cricket team

- Sindhi clothing

- Sindhu Kingdom

- Sufism in Sindh

- Tomb paintings of Sindh

Notes

- ^ a b Sindh's contribution to national economy was 23.7%, or $345 billion (PPP) and $86 billion (nominal) in 2022.[2][3]

- ^ Brooke (2014), p. 296. "The story in Harappan India was somewhat different (see Figure 111.3). The Bronze Age village and urban societies of the Indus Valley are some-thing of an anomaly, in that archaeologists have found little indication of local defense and regional warfare. It would seem that the bountiful monsoon rainfall of the Early to Mid-Holocene had forged a condition of plenty for all, and that competitive energies were channeled into commerce rather than conflict. Scholars have long argued that these rains shaped the origins of the urban Harappan societies, which emerged from Neolithic villages around 2600 BCE. It now appears that this rainfall began to slowly taper off in the third millennium, at just the point that the Harappan cities began to develop. Thus it seems that this "first urbanisation" in South Asia was the initial response of the Indus Valley peoples to the beginning of Late Holocene aridification. These cities were maintained for 300 to 400 years and then gradually abandoned as the Harappan peoples resettled in scattered villages in the eastern range of their territories, into the Punjab and the Ganges Valley....' 17 (footnote):

(a) Giosan et al. (2012);

(b) Ponton et al. (2012);

(c) Rashid et al. (2011);

(d) Madella & Fuller (2006);

Compare with the very different interpretations in

(e) Possehl (2002), pp. 237–245

(f) Staubwasser et al. (2003) - ^ a b 1941 figure taken from census data by combining the total population of all districts (Dadu, Hyderabad, Karachi, Larkana, Nawabshah, Sukkur, Tharparkar, Upper Sind Frontier), and one princely state (Khairpur), in Sindh Province, British India. See 1941 census data here:[104]

- ^ a b 1931 figure taken from census data by combining the total population of all districts (Hyderabad, Karachi, Larkana, Nawabshah, Sukkur, Tharparkar, Upper Sind Frontier), and one princely state (Khairpur), in Sindh Province, British India. See 1931 census data here:[105]

- ^ a b 1921 figure taken from census data by combining the total population of all districts (Hyderabad, Karachi, Larkana, Nawabshah, Sukkur, Tharparkar, Upper Sind Frontier), and one princely state (Khairpur), in Sindh Province, British India. See 1921 census data here:[106]

- ^ a b 1911 figure taken from census data by combining the total population of all districts (Hyderabad, Karachi, Larkana, Sukkur, Tharparkar, Upper Sind Frontier), and one princely state (Khairpur), in Sindh Province, British India. See 1911 census data here:[107]

- ^ a b 1901 figure taken from census data by combining the total population of all districts (Karachi, Hyderabad, Shikarpur, Tharparkar, Upper Sind Frontier), and one princely state (Khairpur), in Sindh Province, British India. See 1901 census data here:[108]

- ^ a b 1901 census: Enumerated as Hindus.

- ^ Including Federal Capital Territory (Karachi)

References

- ^ "Announcement of Results of 7th Population and Housing Census-2023 (Sindh province)" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (www.pbs.gov.pk). 5 August 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "GDP OF KHYBER PUKHTUNKHWA'S DISTRICTS" (PDF). kpbos.gov.pk.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects".

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Subnational HDI - Global Data Lab". Globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ "Welcome to the Website of Provincial Assembly of Sindh". www.pas.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ "LgdSindh - News Blog". LgdSindh. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2006.

- ^ Staff reporter (9 March 2014). "Sindh must exploit potential for fruit production". The Nation, 2014. The Nation. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Markhand, Ghulam Sarwar; Saud, Adila A. "Dates in Sindh". Proceedings of the International Dates Seminar. SALU Press. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Editorial (3 September 2007). "How to grow Bananas". Dawn News, 2007. Dawn News. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Quddus, Syed Abdul (1992). Sindh, the Land of Indus Civilisation. Royal Book Company. ISBN 978-969-407-131-2.

- ^ JPRS Report: Near East & South Asia. Foreign Broadcast Information Service. 1992.

- ^ Judy Wakabayashi; Rita Kothari (2009). Decentering Translation Studies: India and Beyond. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-90-272-2430-9.

- ^ "Properties inscribed on the World Heritage List (Pakistan)". UNESCO. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Choudhary Rahmat Ali (28 January 1933). "Now or Never. Are we to live or perish forever?".

- ^ S. M. Ikram (1 January 1995). Indian Muslims and partition of India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-81-7156-374-6. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ Phiroze Vasunia 2013, p. 6.

- ^ Southworth, Franklin. The Reconstruction of Prehistoric South Asian Language Contact (1990) p. 228

- ^ Burrow, T. Dravidian Etymology Dictionary Archived 1 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine p. 227

- ^ "Sindh, not Sind". The Express Tribune. Web Desk. 12 February 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ Sanyal, Sanjeev (10 July 2013). Land of the seven rivers : a brief history of India's geography. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-342093-4. OCLC 855957425.

- ^ "Archaeological Ruins at Moanjodaro". The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) website. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ "Mohenjo-Daro: An Ancient Indus Valley Metropolis".

- ^ "Mohenjo Daro: Could this ancient city be lost forever?". BBC News. 26 June 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Edwin Bryant (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture. pp. 159–60.

- ^ Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra (1953). Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of Gupta Dynasty. University of Calcutta. p. 197.

- ^ a b Jain 1974, p. 209-210.

- ^ Sikdar 1964, p. 501-502.

- ^ H.C. Raychaudhuri (1923). Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of the Gupta Dynasty. University of Calcutta. ISBN 978-1-4400-5272-9.

- ^ M. A. Dandamaev. "A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire" p 147. BRILL, 1989 ISBN 978-9004091726

- ^ "Hidus could be the areas of Sindh, or Taxila and West Punjab." in Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. 2002. p. 204. ISBN 9780521228046.

- ^ Rafi U. Samad, The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing, 2011, p. 33 ISBN 0875868592

- ^ Dani 1981, p. 37.

- ^ Eggermont 1975, p. 13.

- ^ Thorpe 2009, p. 33.

- ^ Rawlinson, H. G. (2001). Intercourse Between India and the Western World: From the Earliest Times of the Fall of Rome. Asian Educational Services. p. 114. ISBN 978-81-206-1549-6.

- ^ Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I. B. Tauris. p. 17. ISBN 9780857716668.

- ^ Schindel, Nikolaus; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj; Pendleton, Elizabeth (2016). The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: adaptation and expansion. Oxbow Books. pp. 126–129. ISBN 9781785702105.

- ^ a b Wink 1996, pp. 133, 152–153.

- ^ Asif 2016, pp. 65, 81–82, 131–134.

- ^ Wink 1996, p. 151.

- ^ P. 505 The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians by Henry Miers Elliot, John Dowson

- ^ Nicholas F. Gier, FROM MONGOLS TO MUGHALS: RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN INDIA 9TH-18TH CENTURIES, presented at the Pacific Northwest Regional Meeting American Academy of Religion, Gonzaga University, May 2006 [1]. Retrieved 11 December 2006.

- ^ Naik, C.D. (2010). Buddhism and Dalits: Social Philosophy and Traditions. Delhi: Kalpaz Publications. p. 32. ISBN 978-81-7835-792-8.

- ^ P. 164 Notes on the religious, moral, and political state of India before the Mahomedan invasion, chiefly founded on the travels of the Chinese Buddhist priest Fai Han in India, A.D. 399, and on the commentaries of Messrs. Remusat, Klaproth and Burnouf, Lieutenant-Colonel W.H. Sykes by Sykes, Colonel;

- ^ Wink 1991, pp. 152–153.

- ^ El Hareir, Idris; Mbaye, Ravane (2012), The Spread of Islam Throughout the World, UNESCO, p. 602, ISBN 978-92-3-104153-2

- ^ a b MacLean, Derryl N. (1989), Religion and Society in Arab Sind, pp. 126, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-08551-3

- ^ S. A. A. Rizvi, "A socio-intellectual History of Isna Ashari Shi'is in India", Volo. 1, pp. 138, Mar'ifat Publishing House, Canberra (1986).

- ^ S. A. N. Rezavi, "The Shia Muslims", in History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, Vol. 2, Part. 2: "Religious Movements and Institutions in Medieval India", Chapter 13, Oxford University Press (2006).

- ^ El Hareir, Idris; Mbaye, Ravane (2012), The Spread of Islam Throughout the World, UNESCO, pp. 601–602, ISBN 978-92-3-104153-2

- ^ Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1976), Readings in political history of India, ancient, mediaeval, and modern, B.R. Pub. Corp., on behalf of Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies, p. 216

- ^ Tripathi 1967, p. 337.

- ^ Asif 2016, p. 35.

- ^ P. M. ( Nagendra Kumar Singh), Muslim Kingship in India, Anmol Publications, 1999, ISBN 81-261-0436-8, ISBN 978-81-261-0436-9 pg 43-45.

- ^ P. M. ( Derryl N. Maclean), Religion and society in Arab Sindh, Published by Brill, 1989, ISBN 90-04-08551-3, ISBN 978-90-04-08551-0 pg 140-143.

- ^ Abdulla, Ahmed (1987). An Observation: Perspective of Pakistan. Tanzeem Publishers.

- ^ Habib, Irfan (2011). Economic History of Medieval India, 1200-1500. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-2791-1.

- ^ Siddiqui, Habibullah. "The Soomras of Sindh: their origin, main characteristics and rule – an overview (general survey) (1025–1351 CE)" (PDF). Literary Conference on Soomra Period in Sindh.

- ^ "The Arab Conquest". International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics. 36 (1): 91. 2007.

The Soomras are believed to be Parmar Rajputs found even today in Rajasthan, Saurashtra, Kutch and Sindh. The Cambridge History of India refers to the Soomras as "a Rajput dynasty the later members of which accepted Islam" (p. 54 ).

- ^ Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2007). History of Pakistan: Pakistan through ages. Sang-e Meel Publications. p. 218. ISBN 978-969-35-2020-0.

But as many kings of the dynasty bore Hindu names, it is almost certain that the Soomras were of local origin. Sometimes they are connected with Paramara Rajputs, but of this there is no definite proof.

- ^ a b c d Collinet, Annabelle (2008). "Chronology of Sehwan Sharif through Ceramics (The Islamic Period)". In Boivin, Michel (ed.). Sindh through history and representations : French contributions to Sindhi studies. Karachi: Oxford University Press. pp. 9, 11, 113 (note 43). ISBN 978-0-19-547503-6.

- ^ a b Boivin, Michel (2008). "Shivaite Cults And Sufi Centres: A Reappraisal Of The Medieval Legacy In Sindh". In Boivin, Michel (ed.). Sindh through history and representations : French contributions to Sindhi studies. Karachi: Oxford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-547503-6.

- ^ Aniruddha Ray (4 March 2019). The Sultanate of Delhi (1206-1526): Polity, Economy, Society and Culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 43–. ISBN 978-1-00-000729-9.

- ^ "Historical Monuments at Makli, Thatta".

- ^ Census Organization (Pakistan); Abdul Latif (1976). Population Census of Pakistan, 1972: Larkana. Manager of Publications.

- ^ Rapson, Edward James; Haig, Sir Wolseley; Burn, Sir Richard; Dodwell, Henry (1965). The Cambridge History of India: Turks and Afghans, edited by W. Haig. Chand. p. 518.

- ^ U. M. Chokshi; M. R. Trivedi (1989). Gujarat State Gazetteer. Director, Government Print., Stationery and Publications, Gujarat State. p. 274.

It was the conquest of Kutch by the Sindhi tribe of Sama Rajputs that marked the emergence of Kutch as a separate kingdom in the 14th century.

- ^ a b "Directions in the History and Archaeology of Sindh by M. H. Panhwar". Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Archnet.org: Thattah Archived 2012-06-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Census Organization (Pakistan); Abdul Latif (1976). Population Census of Pakistan, 1972: Larkana. Manager of Publications.

- ^ Population Census of Pakistan, 1972: Jacobabad

- ^ The Travels of Marco Polo - Complete (Mobi Classics) By Marco Polo, Rustichello of Pisa, Henry Yule (Translator)

- ^ Bosworth, "New Islamic Dynasties," p. 329

- ^ Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia by Nicholas Tarling p.39. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521663700.

- ^ "Hispania [Publicaciones periódicas]. Volume 74, Number 3, September 1991". Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ Brohī, ʻAlī Aḥmad (1998). The Temple of Sun God: Relics of the Past. Sangam Publications. p. 175.

Kalhoras a local Sindhi tribe of Channa origin...

- ^ Burton, Richard Francis (1851). Sindh, and the Races that Inhabit the Valley of the Indus. W. H. Allen. p. 410.

Kalhoras...were originally Channa Sindhis, and therefore converted Hindoos.

- ^ Verkaaik, Oskar (2004). Migrants and Militants: Fun and Urban Violence in Pakistan. Princeton University Press. pp. 94, 99. ISBN 978-0-69111-709-6.

The area of the Hindu-built mansion Pakka Qila was built in 1768 by the Kalhora kings, a local dynasty of Arab origin that ruled Sindh independently from the decaying Moghul Empire beginning in the mid-eighteenth century.

- ^ "History of Khairpur and the royal Talpurs of Sindh". Daily Times. 21 April 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ a b Solomon, R. V.; Bond, J. W. (2006). Indian States: A Biographical, Historical, and Administrative Survey. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1965-4.

- ^ Baloch, Inayatullah (1987). The Problem of "Greater Baluchistan": A Study of Baluch Nationalism. Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden. p. 121. ISBN 9783515049993.

- ^ Ziad, Waleed (2021). Hidden Caliphate: Sufi Saints Beyond the Oxus and Indus. Harvard University Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780674248816.

- ^ "The Royal Talpurs of Sindh - Historical Background". www.talpur.org. 24 July 2002. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ General Napier apocryphally reported his conquest of the province to his superiors with the one-word message peccavi, a schoolgirl's pun recorded in Punch (magazine) relying on the Latin word's meaning, "I have sinned", homophonous to "I have Sindh". Eugene Ehrlich, Nil Desperandum: A Dictionary of Latin Tags and Useful Phrases [Original title: Amo, Amas, Amat and More], BCA 1992 [1985], p. 175.

- ^ a b c d Roger D. Long; Gurharpal Singh; Yunas Samad; Ian Talbot (8 October 2015), State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security, Routledge, pp. 102–, ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4

- ^ a b I. Malik (3 June 1999), Islam, Nationalism and the West: Issues of Identity in Pakistan, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 56–, ISBN 978-0-230-37539-0

- ^ Gail Minault (1982), The Khilafat Movement: Religious Symbolism and Political Mobilization in India, Columbia University Press, pp. 105–, ISBN 978-0-231-05072-2

- ^ a b Ansari 1992, p. 77.

- ^ Pakistan Historical Society (2007), Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, Pakistan Historical Society., p. 245

- ^ Priya Kumar & Rita Kothari (2016) Sindh, 1947 and Beyond, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 39:4, 775, doi:10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752

- ^ Ayesha Jalal (4 January 2002). Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850. Routledge. pp. 415–. ISBN 978-1-134-59937-0.

- ^ Roger D. Long; Gurharpal Singh; Yunas Samad; Ian Talbot (8 October 2015). State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security. Routledge. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4.

- ^ Pakistan Historical Society (2007). Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society. Pakistan Historical Society. p. 245.

- ^ a b Jalal 2002, p. 415

- ^ Amritjit Singh; Nalini Iyer; Rahul K. Gairola (15 June 2016), Revisiting India's Partition: New Essays on Memory, Culture, and Politics, Lexington Books, pp. 127–, ISBN 978-1-4985-3105-4

- ^ Khaled Ahmed (18 August 2016), Sleepwalking to Surrender: Dealing with Terrorism in Pakistan, Penguin Books Limited, pp. 230–, ISBN 978-93-86057-62-4

- ^ Veena Kukreja (24 February 2003), Contemporary Pakistan: Political Processes, Conflicts and Crises, SAGE Publications, pp. 138–, ISBN 978-0-7619-9683-5

- ^ a b Ansari 1992, p. 115.

- ^ Ansari 1992, p. 122.

- ^ I. Malik (3 June 1999). Islam, Nationalism and the West: Issues of Identity in Pakistan. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 56–. ISBN 978-0-230-37539-0.

- ^ Veena Kukreja (24 February 2003). Contemporary Pakistan: Political Processes, Conflicts and Crises. SAGE Publications. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-7619-9683-5.

- ^ Priya Kumar & Rita Kothari (2016) Sindh, 1947 and Beyond, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 39:4, 776–777, DOI: 10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752

- ^ "Population Census 2023".

- ^ a b c d India Census Commissioner (1941). "Census of India, 1941. Vol. 12, Sind". JSTOR saoa.crl.28215545. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ a b India Census Commissioner (1931). "Census of India 1931. Vol. 8, Bombay. Pt. 2, Statistical tables". JSTOR saoa.crl.25797128. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ a b India Census Commissioner (1921). "Census of India 1921. Vol. 8, Bombay Presidency. Pt. 2, Tables : imperial and provincial". JSTOR saoa.crl.25394131. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ a b India Census Commissioner (1911). "Census of India 1911. Vol. 7, Bombay. Pt. 2, Imperial tables". JSTOR saoa.crl.25393770. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ a b India Census Commissioner (1901). "Census of India 1901. Vols. 9-11, Bombay". JSTOR saoa.crl.25366895. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ "Social Policy and Development Centre |" (PDF). www.spdc.org.pk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2009.

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel, Pearls from Indus Jamshoro, Sindh, Pakistan: Sindhi Adabi Board (1986). See pp. 150.

- ^ "History of Sufism in Sindh discussed". DAWN.COM. 25 September 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ "Can Sufism save Sindh?". DAWN.COM. 2 February 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Rahimdad Khan Molai Shedai; Janet ul Sindh; 3rd edition, 1993; Sindhi Adbi Board, Jamshoro; page no: 2.

- ^ a b "Religious Demographics of Pakistan 2023" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ "Religion in Pakistan (2017 Census)" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "Scheduled castes have a separate box for them, but only if anybody knew". Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "Hindu Population (PK)". Pakistanhinducouncil.org.pk. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ "Hindu's converge at Ramapir Mela near Karachi seeking divine help for their security". The Times of India. 26 September 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Shahid Jatoi (8 June 2017). "Sindh Hindu Marriage Act—relief or restraint?". Express Tribune. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Tunio, Hafeez (31 May 2020). "Shikarpur's Sikhs serve humanity beyond religion". The Express Tribune. Pakistan. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ "CPopulation According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan - Census 1951". Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ "Population Distribution by Religion, 1998 Census" (PDF). Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "TABLE 9 - POPULATION BY SEX, RELIGION AND RURAL/URBAN" (PDF). Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "TABLE 9 : POPULATION BY SEX, RELIGION AND RURAL/URBAN, CENSUS - 2023" (PDF).

- ^ "7th Population and Housing Census - Detailed Results Table-9 Population by sex, religion and rural/urban". Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ https://www.pbs.gov.pk/sites/default/files/population/2023/tables/sindh/dcr/table_11.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Rehman, Zia Ur (18 August 2015). "With a handful of subbers, two newspapers barely keeping Gujarati alive in Karachi". The News International. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

In Pakistan, the majority of Gujarati-speaking communities are in Karachi including Dawoodi Bohras, Ismaili Khojas, Memons, Kathiawaris, Katchhis, Parsis (Zoroastrians) and Hindus, said Gul Hasan Kalmati, a researcher who authored "Karachi, Sindh Jee Marvi", a book discussing the city and its indigenous communities. Although there are no official statistics available, community leaders claim that there are three million Gujarati-speakers in Karachi – roughly around 15 percent of the city's entire population.

- ^ Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2019). "Pakistan - Languages". Ethnologue (22nd ed.).

- ^ "Political and ethnic battles turn Karachi into Beirut of South Asia " Crescent". Merinews.com. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Haig, Malcolm Robert (1894). The Indus Delta Country: A Memoir, Chiefly on Its Ancient Geography and History. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. 1. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ Menon, Sunita. "Queen of Mangoes: Sindhri from Pakistan now in UAE". Khaleej Times. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ a b Khan, Mohammad Hussain (20 December 2021). "The tale of Benazirabad". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ "Pakistan Bureau of Statistics – 6th Population and Housing Census". www.pbscensus.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ Ilyas, Faiza (10 July 2012). "Provincial mammal, bird notified". Dawn. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ "Govt declares Neem 'provincial tree'". Dawn. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ Amar Guriro (14 December 2011). "Our Sindhi symbols – ibex, black partridge". Pakistan Today. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ a b c Sheikh, Yasir (5 November 2012). "Areas of political influence in Pakistan: right-wing vs left-wing". Karachi, Sindh: Rug Pandits, Yasir. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Rehman, Zia ur (26 May 2015). "PML-N braving silent rebellion in Sindh and Karachi leaderships". News International. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Sodhar, Muhammad Qasim. "Turn Right: Sindhi Nationalism and Electoral Politics". Tanqeed, Sodhar. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ "Commissionerate system restored". 26 October 2008. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010.

- ^ "502 Bad Gateway". www.emoiz.com. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ "Commissioner system to be restored soon: Durrani". Archived from the original on 31 July 2012.

- ^ "Sindh: Commissioner system may be revived today". Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ Chandio, Ramzan (12 July 2011). "Commissioners, DCs posted in Sindh". The Nation. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- ^ "Sindh back to 5 divisions after 11 years". Pakistan Today.

- ^ ABDULLAH ZAFAR (21 August 2020). "Sindh Cabinet approves division of Karachi into seven districts". nation.com.pk. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ "Sindh govt to divide Tharparkar in two districts". Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Khan, Tariq Shafiq (2009). Pakistan 2008 Mouza Statistics (PDF). Government of Pakistan: Statistics Division - Agricultural Census Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Provincial Accounts of Pakistan: Methodology and Estimates 1973-2000" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ^ http://siteresources.worldbank.org/PAKISTANEXTN/Resources/293051-1241610364594/6097548-1257441952102/balochistaneconomicreportvol2.pdf

- ^ Gazetteer of the Province of Sind …. government at the "Mercantile" steam Press. 1907.

- ^ "About Sindh". Consulate General of the People's Republic of China in Karachi. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Pakistan: Mining, Minerals and Fuel Resources". AZoMining.com. 15 September 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ "Salient Features of Final Results Census-2017" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ "Population by Level of Education and Rural/Urban". Statistics Division: Ministry of Economic Affairs and Statistics. Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original on 20 July 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ^ "Spotlighting: Sindh Exhibit provides peek into province's rich culture – The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 28 September 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ "Cultural Heritage". wishwebdesign.com =. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ "Sindh celebrates first ever 'Sindhi Topi Day'". Archived from the original on 8 December 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- ^ a b "Tourism in Sindh - The Express Tribune". 22 November 2013.

- ^ Mangan, Tehmina; Brouwer, Roy; Lohano, Heman Das; Nangraj, Ghulam Mustafa (1 April 2013). "Estimating the recreational value of Pakistan's largest freshwater lake to support sustainable tourism management using a travel cost model". Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 21 (3): 473–486. doi:10.1080/09669582.2012.708040. ISSN 0966-9582.

Bibliography

- Ansari, Sarah F.D. (1992). Sufi saints and state power: the pirs of Sind, 1843–1947. Vol. 50. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511563201.

- Asif, Manan Ahmed (2016), A Book of Conquest, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-66011-3

- Brooke, John L. (2014). Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87164-8.

- Dani, A.H. (1981). "Sindhu – Sauvira : A glimpse into the early history of Sind". In Khuhro, Hamida (ed.). Sind through the centuries : proceedings of an international seminar held in Karachi in Spring 1975. Karachi: Oxford University Press. pp. 35–42. ISBN 978-0-19-577250-0.

- Eggermont, Pierre Herman Leonard (1975). Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan and the Siege of the Brahmin Town of Harmatelia. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-6186-037-2.

- Giosan L, Clift PD, Macklin MG, Fuller DQ, et al. (2012). "Fluvial landscapes of the Harappan civilization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (26): E1688–E1694. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109E1688G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112743109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3387054. PMID 22645375.

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1974). Lord Mahāvīra and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-0-8426-0738-4.

- Jalal, Ayesha (4 January 2002), Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-59937-0

- Madella, Marco; Fuller, Dorian Q. (2006). "Palaeoecology and the Harappan Civilisation of South Asia: a reconsideration". Quaternary Science Reviews. 25 (11–12): 1283–1301. Bibcode:2006QSRv...25.1283M. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.10.012. ISSN 0277-3791.

- Malkani, Kewal Ram (1984). The Sindh Story. Allied Publishers.

- Phiroze Vasunia (16 May 2013). The Classics and Colonial India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-01-9920-323-9.

- Ponton, Camilo; Giosan, Liviu; Eglinton, Tim I.; Fuller, Dorian Q.; et al. (2012). "Holocene aridification of India" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (3). L03704. Bibcode:2012GeoRL..39.3704P. doi:10.1029/2011GL050722. hdl:1912/5100. ISSN 0094-8276.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-1642-9.

- Rashid, Harunur; England, Emily; Thompson, Lonnie; Polyak, Leonid (2011). "Late Glacial to Holocene Indian Summer Monsoon Variability Based upon Sediment Records Taken from the Bay of Bengal" (PDF). Terrestrial, Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences. 22 (2): 215–228. Bibcode:2011TAOS...22..215R. doi:10.3319/TAO.2010.09.17.02(TibXS). ISSN 1017-0839.

- Sikdar, Jogendra Chandra (1964). Studies in the Bhagawatīsūtra. Muzaffarpur, Bihar, India: Research Institute of Prakrit, Jainology & Ahimsa. pp. 388–464.

- Staubwasser, M.; Sirocko, F.; Grootes, P. M.; Segl, M. (2003). "Climate change at the 4.2 ka BP termination of the Indus valley civilization and Holocene south Asian monsoon variability". Geophysical Research Letters. 30 (8): 1425. Bibcode:2003GeoRL..30.1425S. doi:10.1029/2002GL016822. ISSN 0094-8276. S2CID 129178112.

- Thorpe, Showick Thorpe Edgar (2009), The Pearson General Studies Manual 2009, 1/e, Pearson Education India, ISBN 978-81-317-2133-9

- Tripathi, Rama Shankar (1967), History of Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0018-2

- Wink, André (1991). Al- Hind: The slave kings and the Islamic conquest. 2. BRILL. ISBN 9004095098.

- Wink, Andre (1996). Al Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-09249-8.

External links

- Sindh Transport Department official website

- Government of Sindh Archived 31 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Guide of Sindh Archived 5 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Map of the districts of Sindh