Energy drink

This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (September 2018) |

A variety of energy drinks in a German supermarket shelf | |

| Type | Functional beverage |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Japan |

| Introduced | 20th century |

| Color | Various |

| Flavor | Various |

| Ingredients | Usually caffeine, various others |

An energy drink is a type of functional beverage containing stimulant compounds, usually caffeine, which is marketed as providing mental and physical stimulation (marketed as "energy", but distinct from food energy). They may or may not be carbonated and may also contain sugar, other sweeteners, or herbal extracts, among numerous other possible ingredients.

They are a subset of the larger group of energy products, which includes bars and gels, and distinct from sports drinks, which are advertised to enhance sports performance. There are many brands and varieties in this drink category.[1][2]

Energy drinks have the effects of caffeine and sugar, but there is little or no evidence that the wide variety of other ingredients have any effect.[3] Most effects of energy drinks on cognitive performance, such as increased attention and reaction speed, are primarily due to the presence of caffeine.[4] Other studies ascribe those performance improvements to the effects of the combined ingredients.[5]

Advertising for energy drinks usually features increased muscle strength and endurance, but there is no scientific consensus to support these claims.[6] Energy drinks have been associated with many health risks, such as an increased rate of injury when usage is combined with alcohol, and excessive or repeated consumption can lead to cardiac and psychiatric conditions.[7][8] Populations at risk for complications from energy drink consumption include youth, caffeine-naïve or caffeine-sensitive, pregnant, competitive athletes and people with underlying cardiovascular disease.[9]

Ingredients and uses

[edit]Energy drinks are usually marketed to young people and provide the health effects of caffeine.[10] Health experts agree that energy drinks which contain caffeine do improve alertness.[10]

There is no reliable evidence that other ingredients in energy drinks provide further benefits, even though the drinks are frequently advertised in a way that suggests they have unique benefits.[10][11] The dietary supplements in energy drinks may be purported to supply benefits, such as for vitamin B12,[10][12] but no claims of using supplements to enhance health in otherwise normal people have been verified scientifically.

Marketing of energy drinks has been particularly directed towards teenagers, with manufacturers sponsoring or advertising at extreme sports events and music concerts, and targeting a youthful audience through social media channels.[13]

Effects

[edit]

Energy drinks have the effects caffeine and sugar provide, but there is little or no evidence that the wide variety of other ingredients have any effect.[3] Most of the effects of energy drinks on cognitive performance, such as increased attention and reaction speed, are primarily due to the presence of caffeine.[4] Advertising for energy drinks usually features increased muscle strength and endurance, but there is little evidence to support this in the scientific literature.[6]

According to the Mayo Clinic, it is safe for the typical healthy adult to consume a total of 400 mg of caffeine a day. This has been confirmed by a panel of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), which also concludes that a caffeine intake of up to 400 mg per day does not raise safety concerns for adults. According to the EFSA this is equivalent to 4 cups of coffee (90 mg each) or 2 1/2 standard cans (250 ml) of energy drink (160 mg each/80 mg per serving).[14][15] Adverse effects associated with caffeine consumption in amounts greater than 400 mg include nervousness, irritability, sleeplessness, increased urination, abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmia), and dyspepsia. In the United States, caffeine dosage is not required to be displayed on product labels for food. However, companies often place the caffeine content of their drinks on the label regardless, and some advocates are urging the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to change this practice.[16][17]

Health problems

[edit]Excessive consumption of energy drinks can have serious health effects resulting from high caffeine and sugar intakes, particularly in children, teens, and young adults.[18][19] Excessive energy drink consumption may disrupt teens' sleep patterns and may be associated with increased risk-taking behavior.[18] Excessive or repeated consumption of energy drinks can lead to cardiac problems, such as arrhythmias and heart attacks, and psychiatric conditions such as anxiety and phobias.[7][8][18] The consumption of caffeinated energy drinks has been associated with adverse effects on cardiovascular health, including increased heart rate and blood pressure, which can pose risks for individuals with underlying heart conditions.[20] In Europe, energy drinks containing sugar and caffeine have been associated with the deaths of athletes.[21] Reviews have noted that caffeine content was not the only factor, and that the cocktail of other ingredients in energy drinks made them more dangerous than drinks whose only stimulant was caffeine; the studies noted that more research and government regulation were needed.[18][22]

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children not consume caffeinated energy drinks.[23]

History

[edit]This article possibly contains original research. No clear distinction between how the term "energy drink" has been used vs today's idea of what it means. (September 2023) |

Dr. Enuf, an "energy building"[24] soft drink containing caffeine and B vitamins, was created in the United States in 1949.[25][26] The New York Times states that "the energy drink, as we know it", however, was born in post World War II Japan.[26] In 1962, Taisho Pharmaceutical produced Lipovitan D, a herbal “energizing tonic” that was sold in minibar-sized bottles. The tonic was originally marketed towards truck drivers and factory workers who needed to stay awake for long shifts. However, in Japan, most of the products of this kind bear little resemblance to soft drinks, and are sold instead in small brown glass medicine bottles, or cans styled to resemble such containers. These eiyō dorinku (literally, 'nutritional drinks') are marketed primarily to salarymen. Bacchus-F, a South Korean drink closely modeled after Lipovitan, also appeared in the early 1960s and targets a similar demographic.[citation needed]

In Europe, Dietrich Mateschitz, an Austrian entrepreneur, introduced the Red Bull product, a worldwide bestseller in the 21st century. Mateschitz developed Red Bull based on the Thai drink Krating Daeng, itself based on Lipovitan. Red Bull became the dominant brand in the US after its introduction in 1997, with a market share of approximately 47% in 2005.[27]

In New Zealand and Australia, the leading energy drink product in those markets, V, was introduced by Frucor Beverages. The product now represents over 60% of market in New Zealand and Australia.[28]

In 2002, Hansen Natural Company introduced the energy drink Monster Energy.[29] Hansen Natural Company changed their name to Monster Beverage Corporation after an agreement by shareholders to change the name after Monster Energy became the largest source of revenue.[30] The company's previous beverages were taken ownership of by the Coca-Cola Company.[31]

The energy shot product, an offshoot of the energy drink, was launched in the US with products such as 5-Hour Energy, which was first released onto the market in 2004. A consumer health analyst explained in a March 2014 media article: "Energy shots took off because of energy drinks. If you’re a white collar worker, you’re not necessarily willing to down a big Monster energy drink, but you may drink an energy shot."[32][33]

In 2007, energy drink powders and effervescent tablets were introduced, whereby either can be added to water to create an energy drink.[34]

On 14 August 2012, the word energy drink was listed for the first time in the Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary.[35]

Variants

[edit]By concentration

[edit]Energy shots

[edit]Energy shots are a specialized kind of energy drink. Whereas most energy drinks are sold in cans or bottles, energy shots are usually sold in smaller 50ml bottles.[36] Energy shots can contain the same total amount of caffeine, vitamins or other functional ingredients as their larger versions, and may be considered concentrated forms of energy drinks. The marketing of energy shots generally focuses on their convenience and availability as a low-calorie "instant" energy drink that can be taken in one swallow (or "shot"), as opposed to energy drinks that encourage users to drink an entire can, which may contain 250 calories or more.[37] A common energy shot is 5-hour Energy which contains B vitamins and caffeine in an amount similar to a cup of coffee.[38]

By ingredient

[edit]Caffeinated alcoholic drink

[edit]Energy drinks such as Red Bull are often used as mixers with alcoholic drinks, producing mixed drinks such as Vodka Red Bull which are similar to but stronger than rum and coke with respect to the amount of caffeine that they contain.[39] Sometimes this is configured as a bomb shot, such as the Jägerbomb or the F-Bomb—Fireball Cinnamon Whisky and Red Bull.[40]

Caffeinated alcoholic drinks are also sold in some countries in a wide variety of formulations. The American products Four Loko and Joose originally combined caffeine and alcohol before caffeinated alcoholic drinks were banned in the US in 2010.[41][42][43]

Chemistry

[edit]

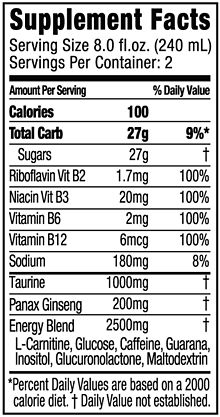

Energy drinks generally contain methylxanthines (including caffeine), B vitamins, carbonated water, and high-fructose corn syrup or sugar (for non-diet versions). Other common ingredients are guarana, yerba mate, açaí, and taurine, plus various forms of ginseng, maltodextrin, inositol, carnitine, creatine, glucuronolactone, sucralose or ginkgo biloba.[10]

In the United States, the caffeine content of energy drinks is in the range of 40 to 250 mg per 8 fluid ounce (237 ml) serving.[44] The FDA recommends that 400 mg per day is safe for adults, while 1200 mg per day can be toxic.[44]

Demographics

[edit]Globally, energy drinks are typically attractive to youths and young adults.[45]

Sales and trends

[edit]

In 2017, global energy drink sales were about 44 billion euros.[46] In 2017, manufacturers were modifying the composition of energy drinks for reduced or no sugar content and lower calories, caffeine content, "clean" labels to reflect the use of organic ingredients, exotic flavors, and ingredients that may affect mood.[46]

Market share

[edit]In 2020, Red Bull had the largest global market share among energy drinks, at 43%, followed by Monster Energy at 39%, Rockstar Energy at 10%, and Amp and NOS, at 3% each.[47]

Regulations

[edit]Some countries have certain restrictions on the sale and manufacture of energy drinks. A ban was challenged in the European Court of Justice in 2004 and consequently lifted.[48]

Australia and New Zealand

[edit]

In Australia and New Zealand, energy drinks are regulated under the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code; limiting the caffeine content of 'formulated caffeinated beverages' (energy drinks) at 320 mg/L (9.46 mg/oz) and soft-drinks at 145 mg/L (4.29 mg/oz). Mandatory caffeine labeling is issued for all food products containing guarana in the country,[49] and Australian energy drink labels warn consumers to drink no more than two cans per day.[50] Bridgetown in Western Australia became the first place in Australia to ban the sale of energy drinks to persons under 18 years for four months as of February 2023.[51]

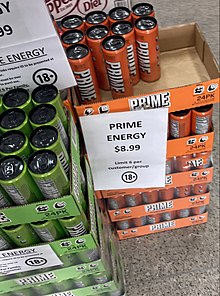

Canada

[edit]Canada limits the amount of caffeine per serving to 180 mg. Energy drinks are also subject to certain labelling requirements.[52] Some imported energy drinks have surpassed the legal limit and were recalled.[53][54] The Canada Border Services Agency is supposed to stop such products from entering the country but does not often patrol energy drinks to verify that they meet regulations.[55]

Colombia

[edit]In 2009 under the Ministry of Social Protection, Colombia prohibited the sale and commercialization of energy drinks to minors under the age of 14.[56]

Denmark

[edit]In 1997, Denmark banned the sale of Red Bull. The Danish Veterinary and Food Administration criticized the functional beverages' added ingredients such as B vitamins, inositol, glucuronolactone, and taurine. It argued that nutritional supplements should be added to foods only when necessary for public health, such as in the case of iodised salt. High caffeine content was also stated as an issue – only amounts up to 150 mg/L were allowed in beverages; in 2009 the limit was raised to 320 mg/L and taurine and glucuronolactone were approved as ingredients, making energy drinks legal.[57][58] As of 2024[update], the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration advises against energy drink consumption for children; with only limited consumption of energy drinks (250 mL (8.5 U.S. fl oz) per day, assuming no other caffeine intake) for children between 15 and 17 years old.[59]

Latvia

[edit]In June 2016, Latvia banned the sale of energy drinks containing caffeine or stimulants like taurine and guarana to people under the age of 18.[60]

Lithuania

[edit]In November 2014, Lithuania became the first country in the EU to ban the selling of energy drinks to anyone under the age of 18. The Baltic state placed the ban in reaction to research showing how popular energy drinks were among minors. According to the AFP reports roughly 10% of school-aged Lithuanians say they consume energy drinks at least once a week.[61]

Norway

[edit]Norway did not allow Red Bull for a time due to the high caffeine and taurine content. Classified as a drug, only limited amounts were allowed to be imported for personal use. In May 2009, it became legal to sell in Norway as the ban was in conflict with the European Economic Area's laws on free competition. The Norwegian version has reduced levels of vitamin B6.[62][63] The Norwegian Food Safety Authority initially recommended an age limit on the sale of energy drinks in 2019. In 2024 the Norwegian Consumer Council called for an age limit after seeing energy drink sales increase dramatically since 2019. The Food Safety Authority, as of 2024[update], now disagrees with an age limit as it states it is hard to ascertain if children, specifically, are drinking more energy drinks.[64][65] A majority of Norwegians support an age limit on energy drink purchases.[66]

Poland

[edit]Since 1 January 2024, energy drinks have been banned for individuals under the age of 18.[67]

Russia

[edit]In November 2012, President Ramzan Kadyrov of Chechnya (Russian Federation) ordered his government to develop a bill banning the sale of energy drinks, arguing that as a form of "intoxicating drug", such drinks were "unacceptable in a Muslim society". Kadyrov cited reports of one death and 530 hospital admissions in 2012 due to "poisoning" from the consumption of such drinks. A similar view was expressed by Gennady Onishchenko, Chief Sanitary Inspector of Russia.[68]

United Kingdom

[edit]In 2001, the UK Committee on Toxicity investigated Red Bull, finding it safe but issuing a warning against its consumption by children and pregnant women.[48]

In 2009, a school in Hove, England, requested that local shops refrain from selling energy drinks to students. Headteacher Falklanda Sanders added that "This was a preventative measure, as all research shows that consuming high-energy drinks can have a detrimental impact on the ability of young people to concentrate in class." The school negotiated for their local branch of the Tesco supermarket to display posters asking students not to purchase the products.[69] Similar measures were taken by a school in Oxted, England, which banned students from consuming drinks and sent letters to parents.

While not yet age-restricted by legislation, all major UK supermarkets have agreed to voluntarily stop the sale of energy drinks to under-16s.[70] The UK government plans to end the sale of energy drinks to under-16s in the future.[71]

In January 2018, many United Kingdom supermarkets banned the sale of energy drinks containing more than 150 mg of caffeine per liter to people under 16 years old;[72] this was followed by the UK government announcing that it planned to ban all sales of energy drinks to minors in 2019.[73] However, in 2022 such plans were reported to have been scrapped by Health Secretary Sajid Javid.[74]

United States

[edit]As of 2013 in the United States, some energy drinks, including Monster Energy and Rockstar Energy, were reported to be rebranding their products as drinks rather than as dietary supplements. As drinks they would be relieved of FDA reporting requirements with respect to deaths and injuries and can be purchased with food stamps, but must list ingredients on the can.[75]

Some places ban the sale of prepackaged caffeinated alcoholic drinks, which can be described as energy drinks containing alcohol. In response to these bans, the marketers can change the formula of their products.[76]

Uzbekistan

[edit]In January 2019, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev of Uzbekistan signed a law that imposes a number of restrictions on energy drinks. To protect the younger generation, a rule was introduced prohibiting the sale of energy drinks to persons under the age of 18. Advertising of energy drinks was prohibited on television and radio from 7:00 to 22:00. It was also completely banned in printed publications intended primarily for children and adolescents, in medical, sports and educational institutions.[77][clarification needed]

India

[edit]In India, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) regulates the manufacturing, packaging, labeling, and sale of energy drinks. As recommended by FSSAI, taurine is limited to 2000 mg/day, D-glucuronic-Y-lactone is limited to 1200 mg/day, Inositol is limited to 100 mg/day, and pantothenic acid is limited to 10 mg/day.[78]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Miyeong, Han (19 February 2012). "Energy drink, does it really work?". Health Chosun News. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Haesoo, Lee (11 November 2014). "The four main ingredients of energy drinks". Global Economic. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ a b McLellan TM, Lieberman HR (2012). "Do energy drinks contain active components other than caffeine?". Nutr Rev. 70 (12): 730–44. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00525.x. PMID 23206286.

- ^ a b Van Den Eynde F, Van Baelen PC, Portzky M, Audenaert K (2008). "The effects of energy drinks on cognitive performance". Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie. 50 (5): 273–81. PMID 18470842.

- ^ Alford, C.; Cox, H.; Wescott, R. (1 January 2001). "The effects of red bull energy drink on human performance and mood". Amino Acids. 21 (2): 139–150. doi:10.1007/s007260170021. PMID 11665810. S2CID 25358429. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ a b Mora-Rodriguez R, Pallarés JG (2014). "Performance outcomes and unwanted side effects associated with energy drinks". Nutr Rev. 72 (Suppl 1): 108–20. doi:10.1111/nure.12132. PMID 25293550.

- ^ a b Sanchis-Gomar F, Pareja-Galeano H, Cervellin G, Lippi G, Earnest CP (2015). "Energy drink overconsumption in adolescents: implications for arrhythmias and other cardiovascular events". Can J Cardiol. 31 (5): 572–5. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2014.12.019. hdl:11268/3906. PMID 25818530.

- ^ a b Petit A, Karila L, Lejoyeux M (2015). "[Abuse of energy drinks: does it pose a risk?]". Presse Med. 44 (3): 261–70. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2014.07.029. PMID 25622514.

- ^ Higgins, John; Yarlagadda, Santi; Yang, Benjamin; Higgins, John P.; Yarlagadda, Santi; Yang, Benjamin (June 2015). "Cardiovascular Complications of Energy Drinks". Beverages. 1 (2): 104–126. doi:10.3390/beverages1020104.

- ^ a b c d e Meier, Barry (1 January 2013). "Energy Drinks Promise Edge, but Experts Say Proof Is Scant". The New York Times. New York City. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (2011). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims from Energy Drinks". EFSA Journal. 9 (4): 2035 [19 pp.] doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2035. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims". EFSA Journal. 8 (10): 1756. 2010. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1756. Archived from the original on 13 November 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ Plamondon, Laurie (2013). "Energy Drinks: Threatening or Commonplace? An Update" (PDF). TOPO (6): 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ Preszler, Buss. "How much is too much?". mayoclinic.org. Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ "Scientific Opinion on the safety of caffeine". EFSA Journal. 13 (5). May 2015. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4102.

- ^ Aubrey, Allison (24 September 2008). Warning: Energy Drinks Contain Caffeine (Radio broadcast). Morning Edition. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018.

- ^ Meier, Barry (19 March 2013). "Doctors Urge F.D.A. to Restrict Caffeine in Energy Drinks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Al-Shaar, Laila; Vercammen, Kelsey; Lu, Chang; Richardson, Scott; Tamez, Martha; Mattei, Josiemer (31 August 2017). "Health Effects and Public Health Concerns of Energy Drink Consumption in the United States: A Mini-Review". Frontiers in Public Health. 5: 225. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2017.00225. ISSN 2296-2565. PMC 5583516. PMID 28913331.

- ^ "What About Energy Drinks for Kids?". Stanford Children's Health, Stanford University. 2019. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Reissig, Chad J.; Strain, Eric C.; Griffiths, Roland R. (January 2009). "Caffeinated energy drinks—A growing problem". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 99 (1–3): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.001. ISSN 0376-8716. PMC 2735818. PMID 18809264.

- ^ Clauson KA, Shields KM, McQueen CE, Persad N (2008). "Safety issues associated with commercially available energy drinks". J Am Pharm Assoc. 48 (3): e55–63, quiz e64–7. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07055. PMID 18595815.

- ^ Emily A. Fletcher; Carolyn S. Lacey; Melenie Aaron; Mark Kolasa; Andrew Occiano; Sachin A. Shah (May 2017). "Randomized Controlled Trial of High-Volume Energy Drink Versus Caffeine Consumption on ECG and Hemodynamic Parameters". Journal of the American Heart Association. 6 (5): e004448. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.004448. PMC 5524057. PMID 28446495.

- ^ "Kids Should Not Consume Energy Drinks, and Rarely Need Sports Drinks, Says AAP". American Academy of Pediatrics. 30 May 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ "New-Type Drink, Dr. Enuf; Fleming To Manage Business". Johnson City Press. 21 June 1951. p. 3. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ Gorvett, Zaria (9 June 2023). "Why is there taurine in energy drinks?". BBC. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ a b Engber, Daniel (6 December 2013). "Who Made That Energy Drink?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ "Soda With Buzz". Forbes, Kerry A. Dolan. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2005.

- ^ "Our brands – V". Frucor. Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ "What's Hot: Hansen Natural". April 2002. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ "New Stock Ticker Press release" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ "Coke Takes Ownership of Monster's Non-Energy Business". Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ Roberto A. Ferdman (26 March 2014). "The American energy drink craze in two highly caffeinated charts". Quartz. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ O'Connor, Clare (8 February 2012). "The Mystery Monk Making Billions With 5-Hour Energy". Forbes. Forbes LLC. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ "Caffeine Experts at Johns Hopkins Call for Warning Labels for Energy Drinks - 09/24/2008". Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ Italie, Leanne. "F-bomb makes it into mainstream dictionary". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Miller, Kevin (1 February 2017). "As more 'nips' bottles litter Maine landscape, group calls for 15-cent deposit". Portland Press Herald. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ Klineman, Jeffrey (30 April 2008). ""Little competition: energy shots aim for big" profits". Bevnet.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ "What's In A 5-hour ENERGY Shot?". 5-hour ENERGY. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT, Bardgett ME, Howard MA (2011). "Effects of energy drinks mixed with alcohol on behavioral control: Risks for college students consuming trendy cocktails". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 35 (7): 1282–92. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01464.x. PMC 3117195. PMID 21676002.

- ^ Hoare, Peter (9 January 2014). "5 Awesome Drinks You Can Make With Fireball Cinnamon Whisky". Food & drinks. MTV. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ FDA (3 November 2010). "List of Manufacturers of Caffeinated Alcoholic Beverages". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Zezima, Katie (26 October 2010). "A Mix Attractive to Students and Partygoers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 October 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Bruni, Frank (30 October 2010). "Caffeine and Alcohol: Wham! Bam! Boozled". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ a b "Spilling the beans: How much caffeine is too much?". US Food and Drug Administration. 12 December 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Visram, Shelina; Crossley, Stephen J.; Cheetham, Mandy; Lake, Amelia (31 May 2016). "Children and young people's perceptions of energy drinks: A qualitative study". PLOS ONE. 12 (11): e0188668. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0188668. PMC 5708842. PMID 29190753.

- ^ a b Insights, Innova Market (28 June 2018). "Energy Drink Sales Still on the Rise, Despite Slowdown in Innovation". Nutritional Outlook. May 2018 Issue. 21 (4). Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ "Energy Drink Market Share | T4". www.t4.ai. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ a b "French ban on Red Bull (drink) upheld by European Court". Medicalnewstoday.com. 8 February 2004. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ^ "Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code – Standard 2.6.4 – Formulated Caffeinated Beverages – F2009C00814". comlaw.gov.au. Department of Health and Ageing (Australia). 13 August 2009. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ Pogson, Jenny (9 May 2012). "Energy drinks pack more punch than you might expect". ABC. Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ^ "WA town bans sale of energy drinks to under 18s to combat declining mental health - ABC News".

- ^ "Caffeinated energy drinks". Government of Canada. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ La Grassa, Jennifer. "Highly caffeinated version of Prime Energy drink ordered recalled by federal government". CBC News. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Casaletto, Lucas (11 January 2024). "Health Canada recalls more caffeinated energy drinks". CityNews Everywhere. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ La Grassa, Jennifer. "Prime Energy drinks pulled from Canadian shelves — but how did they even get here?". CBC News. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ RESOLUCION 4150 DE 2009 (octubre 30). Diario Oficial No. 47.522 de 3 de noviembre de 20 Archived 3 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. invima.gov.co

- ^ "Energidrik sat ind mod danske fødevarerregler". Dagbladet Information (in Danish). 8 July 1998. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ Larsen, Søren (17 November 2009). "Omdiskuteret koffeindrik nu i Danmark". DR (in Danish). Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ "Derfor er energidrikke ikke for børn". Danish Veterinary and Food Administration (in Danish). Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ Latvia bans sales of energy drinks to under-18s Archived 15 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press. 1 June 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2017

- ^ "A Country In Europe Bans Energy Drinks For Minors". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ Berg, Lorentz (23 April 2009). "Red Bull blir tillatt i Norge". NRK (in Norwegian Bokmål). Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ Holmene, Guro (3 December 2009). "Hvor farlig er egentlig Red Bull?". Nettavisen (in Norwegian). Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ Brenden, Marcus (11 January 2024). "Vil ha aldersgrense på energidrikk". DinSide (in Norwegian). Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ "Aldersgrense på energidrikk: Forbrukerrådet i klinsj med Mattilsynet". Dagens Medisin (in Norwegian Bokmål). Norwegian News Agency. 12 January 2024. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ Framnes, Andreas (16 May 2023). "Stabilt og høgt fleirtal for aldersgrense ved sal av energidrikk". Norwegian Consumer Council (in Norwegian Nynorsk). Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ "Poland bans energy drinks for underaged - English Section - polskieradio.pl". polskieradio.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ "Kadyrov Vows to Ban Energy Drinks". The Moscow Times. 21 November 2012. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ "Pupils facing energy drink 'ban'". BBC News. 7 October 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ^ "Ending the sale of energy drinks to children". GOV.UK. 30 August 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s – consultation document". GOV.UK. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Smithers, Rebecca (5 March 2018). "UK supermarkets ban sales of energy drinks to under-16s". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Deutrom, Rhian; Newton Dunn, Tom (17 July 2019). "UK Government to ban the sale of energy drinks to minors". ABC News. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ "Government's U-turn on energy drink ban is welcome". Institute of Economic Affairs. 27 June 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ Barry Meier (19 March 2013). "In a New Aisle, Energy Drinks Sidestep Some Rules". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ "Four Loko Changing Its Formula". NBC Chicago. 17 November 2010. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ "Продажу и рекламу "энергетиков" ограничили". Gazeta.uz (in Russian). 10 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ "F. No. P.15025/93/2011-PFA/FSSAI" (PDF). FSSAI. 2 December 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Bagchi, D. (2017). "Chapter 26: Caffeine-Containing Energy Drinks/Shots: Safety, Efficacy and Controversy". Sustained Energy for Enhanced Human Functions and Activity. Elsevier Science. pp. 423–445. ISBN 978-0-12-809332-0. Retrieved 23 October 2018.