Assen Jordanoff

Assen Hristov Jordanoff | |

|---|---|

Jordanoff in 1939 | |

| Born | September 2, 1896 |

| Died | October 19, 1967 (aged 71) White Plains, New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | Bulgarian |

| Occupation(s) | Inventor, engineer, aviator |

Assen "Jerry" Jordanoff (Bulgarian: Асен Христов Йорданов, born Asen Hristov Yordanov, September 2, 1896 - October 19, 1967) was a Bulgarian-American[1] inventor, engineer, and aviator. Jordanoff is considered to be the founder of aeronautical engineering in Bulgaria, as well as a contributor to the development of aviation in the United States.

He occupied a distinct place among pilots of his time, the golden age of airmanship; in America, Jordanoff gained almost legendary status for his many roles as test pilot, airmail and air taxis pilot, stunt pilot, and flying instructor.

He worked as an engineer for a number of companies, including Curtiss-Wright, Boeing, Lockheed, North American, Consolidated, Chance-Vought, Douglas and Piper, where he produced instruction books and manuals for famous airplanes such as the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, the North American B-25 Mitchell, the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, and the Douglas DC-3. Jordanoff was also well known for his numerous educational publications on aeronautics, including his inventions outside the realm of aviation.[2][3]

Background

[edit]Asen Hristov Yordanov was the son of a polyglot economist/chemist, Hristo Yordanov. Hristo graduated from the University of Stuttgart in Germany and later obtained a doctorate from the University in Aachen, Germany, where he specialized in the analysis and production of wool and later silk, publishing several important findings on the process.

In Bulgaria, Hristo worked in the Ministry of Economics and Agriculture as well as the Sofia bank. The Yordanov's were fairly wealthy, and owned several coal and copper mines, as well as a family farm. In turn, Asen was educated early. Asen's mother, Dochka Tsoneva, was the daughter of a rich tobacco producer from Razgrad. She studied piano and opera singing in Turin, Italy. Very well-read, Tsoneva found an interest in fine cuisine and published a famous cookbook. She also wrote poems and a number of plays, not meant to be published. Asen had five siblings. His sister Milka Toteva, a violinist, also made a successful career in the United States.

Childhood and youth

[edit]From a very young age, Asen Yordanov was interested in flight. He built kites as a child, and as an adolescent attended lectures on physics at the local university. In his teens, Yordanov invented a dark box, a simple substitution to the use of an entire dark room in photograph development. Later, his father would take Yordanov to Italy, Switzerland and France, where Yordanov learned of the many innovations in transportation, notably the motorcycle. Asen was temporarily lodged in a boarding school in Geneva, where he learned French. He continued his studies in Bulgaria.

The glider

[edit]In 1912, at the age of 16, Yordanov built his first workable glider. A local Bulgarian newspaper, dated February 16, 1912, published an article entitled 'First Bulgarian glider', which read:

- In the last few days, on the field between the infantry camp and the pioneer barracks, a very young Bulgarian aviator drills with his glider built by himself. He is a high school schoolboy, Asen Yordanov, the son of the Administrator of the Bank of Agriculture. He is fifteen, passionately keen on aviation and as a child fashioned toys that could fly. Last year, when visiting France and Italy, he saw the biplane of Maslennykov and Tchernyak, and from then on thought seriously to conquer the air himself. His glider is a very simple, light affair, based on the constructions of the Wright brothers and of Farman. It is 7 meters long, 1.20 m wide, with a surface area of 14 m2 and weights 23 kg. Yesterday he flew for over 12 minutes and reached an altitude of 10 to 12 meters. This young man's glider deserves praise, especially from aviation specialists.

The exact date of the first flight is unclear, but after it, on February 5, the young flier made a second test flight in the presence of an official commission. Young Asen was invited to take another trip to France by a rich couple from Rousse, who had no children, and to go with them on summer holiday to Paris. In 1912, the first Salon de l'Aviation took place in Paris, presenting the latest aeronautic achievements and the latest planes, demonstrated by the top pilots of the day.

In turn, Yordanov, above all, planned to find a means of admission to the well-known Blériot school in Étampes, knowing fully well the unlikelihood of a 16-year-old boy from then newly formed Bulgaria to gain admittance. This was until he met the well-known Bulgarian aviator Lieutenant Simeon Petrov, who introduced him to Louis Blériot himself.

He wasn't officially enrolled and there was no diploma for him, but attending the famous flying school in the company of great aviators played a huge role in Yordanov's educational development. After graduation, all the Bulgarians in the school were gathered and notified that the Turks are planning to invade Bulgaria.

Balkan Wars

[edit]The First Balkan War, led by Bulgaria, Serbia, and Greece against Turkey, was shortly followed by the Second Balkan War, led against Bulgaria by its former allies. At 17, Asen Yordanov volunteered for the army, with his father's reluctant consent. Though never in any imminent danger, Asen Yordanov served his part during the war as car driver; most of his time he frequented the airplane hangars. Colonel Radul Milkov would later recall:

- I would often see the boy, drawing paper in hand, sitting in hangars or in the repair shop and copying the design of the parts from dismantled machines. He would also note down measurements of the length, height and width of this or that part, for instance the ribs and flat surfaces of the plane or all that made up the fuselage.

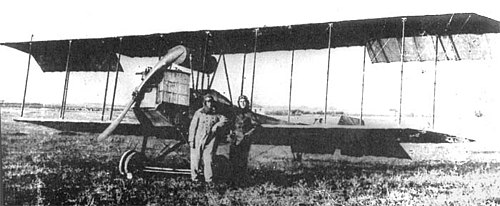

In the Aeroplanno Otdelenie division, Asen Yordanov gained expertise, he designed the first Bulgarian-made airplane, and it was built in the summer of 1915. Yordanov test flew the plane, and it was subsequently named the Diplane (biplane) Yordanov-1. He sold the plane's design to the military and they started to produce it. In one year's time Bulgaria already had 23 airplanes.

August 10, 1915, was considered the beginning of Bulgarian aircraft industry. Yordanov already became known as designer, mathematician, and inventor at his young age. He introduced a valuable new device, namely a feature which prevents the plane from losing altitude, into the new plane.

Asen Yordanov's airplane was at a first look similar to the planes of that time. It was a biplane with relatively short wings, to decrease the body weight and with increased spacing between them to improve the aerodynamic effect of the lower wing. The wing section was similar to that of Albatros. The cockpit and the fuselage were conceived with great care to diminish drag. The landing gear was reinforced with double tires for stability and safety when landing. The tail, vertical and horizontal stabilizers and the ailerons were similar to those built by Louis Blériot. The innovation that helped at landing and at recovery from stalls was something like contemporary flaps, added between the wings.

Yordanov was awarded a scholarship to study abroad for his construction. His next and even more ambitious project was a heavier multi-engine plane. Unfortunately the rise of World War I cancelled his plans.

Adulthood

[edit]World War I

[edit]After finishing secondary school in Sofia, Yordanov was drafted for World War I. He entered the military school at Bozhuriste, near Sofia. On graduation, Jordanoff was promoted to lieutenant and was assigned to the air force. He took part as a pilot in 84 military missions. He ended the war being awarded several insignias of honor, most important of which was the Order for bravery. The war was disastrous for Bulgaria, leaving the country to deal with heavy war reparations and practically destroyed economy.

Emigration to America

[edit]In May 1921 Asen Yordanov and his wartime friend, Alexander Stoyanov, read about a contest to fly around the world in 100 days. The first plane to make it would win one million dollars. Yordanov and his partner were fully supported by the then prime-minister Aleksandar Stamboliyski and were granted US$6,000 /participation fee-US$2500/ by the Bulgarian Ministry of War to participate in the initiative, and they traveled to the US. However, Yordanov and Stoyanov were the only candidates and therefore the contest was postponed and later canceled. Nonetheless, Yordanov decided to remain in the United States, where he later found his new home. He also anglicized his surname to "Jordanoff".

Aviation career

[edit]Faced with the dilemma of knowing absolutely no English, Assen Jordanoff began his life in America shoveling snow in New York for small pay. After the snow melted, Jordanoff was able to find a job at a construction work on a skyscraper. Having a job, he spent all his free time at the Public Library, studying English by himself or reading books and manuals on subjects such as aeronautics, machinery, and mechanics. At that time he became known among his friends and colleagues as Jerry, rather than Assen, a familiar name that would stick with him for the rest of his life.[citation needed]

Jordanoff then got a job at the Curtiss-Wright Corporation. Having his English improved, Assen Jordanoff went on to take university courses in engineering, aeronautics, radio electronics, physics, and chemistry. At the same time he graduated from a flying school; his instructor was William A. Winston, who was also Charles Lindbergh's flight instructor. Jordanoff moved later to Curtiss-Wright, therefrom he would emerge as a test pilot and in parallel as a sales manager, a pilot of air taxis, a stunt pilot and above all a flying instructor. He also specialized in flying under complex weather conditions. Jordanoff was still just in his late 20s. Jordanoff was invited by Thomas Edison to visit him at his home in Menlo Park, New Jersey, as Edison was at the stage of developing a proto-radar and was also interested in helicopters, a research project in which Assen Jordanoff was involved at the same time. They collaborated designs and worked together for several months.

Later years

[edit]Jordanoff's business

[edit]In the 1930s and early 1940s Jordanoff wrote a number of illustrated books on problems of aviation, which became a Bible for future aviators. More than 750,000 copies of his books were sold in the US. Some of them were translated in other languages.

After 1940 began a major period in Assen Jordanoff's career. During the next ten years, he established and presided over his own business enterprises: The Jordanoff Aviation Corporation, followed by The Jordanoff Corporation and then The Jordanoff Company, before the creation in 1946 of Jordanoff Electronics. In aeronautics, the Jordanoff companies collaborated with such firms as Douglas, Chance-Vought, Lockheed, Curtiss-Wright, McDonnell, Boeing, North American, Consolidated, and Piper.

At the request of many, Jordanoff, as a designer and engineer within his own enterprise, compiled instruction books and manuals for the operation and maintenance, inspection and repair for some well-known aircraft such as the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, a very versatile aircraft used during World War II mainly as high-speed, high-altitude fighter, long-range escort fighter and photo reconnaissance plane; the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, America's foremost fighter in service when World War II began; the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, the best long-range bombers in World War II; the Consolidated B-24 Liberator and the North American B-25 Mitchell bombers, and the Douglas DC-3 transport aircraft.

A very important activity was the preparation and the distribution of thousands of copies of descriptive books and practical manuals for aircraft. Jordanoff also became renowned for his many articles and publishing on aviation, as well as his commentaries and editorials. He was presented as a prominent authority on all the areas of aviation. Jordanoff eventually became the largest American publisher and editor of specialized military manuals.

In the 1940s Jordanoff was assigned the task by the United States Department of Defense to prepare instruction manuals for military aircraft, submarines and aircraft carriers, on topics like land support with radio equipment, air meteorology, theoretic and flight preparation of the pilots for diurnal and nocturnal piloting. These were for crew use, inspection, maintenance and repair.

Aside from his many patents on plane design, Jordanoff also introduced the so-called Jordaphone from his Electronics company, a wireless telephone, with an answering function and amplifier and intercom functions. It was the first of its kind, and preceded the modern inventions of the answering machine and tape recorder by 5 to 30 years. Another invention was the Frozen Gasoline System for airplanes.

The idea was to super-cool the fuel in an aircraft's tank with dry ice and alcohol, thus making it inflammable. This system was never finally implemented, but its principles were later adopted in different forms. Further inventions of note included The Reverse Thrust device, which was made to decrease the specific fuel consumption and to increase the thrust of jet engines. The world's first air bag, meant to ensure the safety of pilots and automobile drivers alike, was designed by Jordanoff in (1957).[citation needed]

The Stratoport resumed Jordanoff's interest in aviation. A special company was established: The Stratoport Corporation of America (1956). It owned the patent issued for a field of two unidirectional no-cross runways, set end-to-end and elevated to slow-down planes that are landing and to speed-up those taking off. The runways were screened by high perforated fences that reduced crosswinds. The high screens were also expected to reduce the noise as well as the elevated ends to reduce the length and the area needed for runways. Nonetheless, as was the case with the Jordaphone, the new concept was too ambitious and modernistic.

Jordanoff married in 1929 Alice Grant Patton. She was ten years older than he was. They divorced in 1942. In 1942 he married his second wife Diana. They divorced in 1950 after his financial collapse. In 1955 he married Lucile Andrews. When in 1962 Jordanoff retired, he settled with her in a small cottage in Harrison, New York.

Legacy

[edit]Jordanoff's popularity in America became almost legendary, as he was often the subject of many anecdotes and arguments. Jordanoff was made an honorary citizen of New York City, his name appeared in Who's Who. The Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum holds his papers and mementoes.[4]

Assen Jordanoff died October 19, 1967, aged 71, in St. Angels Hospital in White Plains, New York. His ashes were dispersed from a plane by some of his friends.

Jordanoff Bay in Davis Coast on the Antarctic Peninsula, Antarctica is named after Assen Jordanoff.[5]

Jordanoff's writings

[edit]- Assen Jordanoff, Flying and How to Do It, Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1932, 1936, 1940; illustrated by Larry Whittington

- Assen Jordanoff, Your Wings, Funk and Wagnalls, 1936, 1939–1940, 1942[6][7]

- Assen Jordanoff, Through the Overcast: The Weather and the Art of Instrument Flying, Funk and Wagnalls, New York – London, 1938–1939, 1940–1941, 1943

- Assen Jordanoff, Safety in Flight, Funk & Wagnalls, New York – London, 1941, 1942

- Assen Jordanoff, Jordanoff's Illustrated Aviation Dictionary, Harper & Brothers, New York – London, 1942[8][9][10]

- Assen Jordanoff, The Man Behind the Flight: A ground Course for Aviation Mechanics and Airmen, Harper & Brothers, New York – London, 1942

- Assen Jordanoff, Power and Flight, Harper & Brothers, New York – London, 1944

- Assen Jordanoff, Men and Wings, Curtiss – Wright, New York, 1942.

Articles

[edit]- "Sport Flying is Hailed to Giver Higher Horizons: High Cost of Plane Per Hour Becomes Economy When Compared with Car on Mileage Basis", The New York Times, June 15, 1930, pg. XX5;

- "Diver Flies, Flyer Dives", Popular Science Monthly, January 1931;

- "Unit Parachutes Called Practical: Flier Believes Transport Planes Adaptable To Use of Packs—No Fear Complex", Wide World Photo, The New York Times, Apr 26, 1931, pg. XX8;

- "Will Autogiro Banish Present Plane", Popular Science Monthly, March 1931;

- "Check for Plane Lift: Pilot Urges Revolution Recorder in Place of Time Log: Stunts Bring Extra Strains. Fixes Time for Overhaul.", The New York Times, July 5, 1931, pg. 97;

- "Thrills I Get in Piloting Air Taxis", Popular Science Monthly, July 1931;

- "What Pupils Taught Me About Flying", Popular Science Monthly, November 1931;

- "Flying", Popular Science Monthly, January 1932;

- "The First Fighting Squadron", Sportsman Pilot, February 1932;

- "Stunt Flying", Popular Science Monthly, May 1932.

About Jordanoff

[edit]- Assen Jordanoff and Aviation by Milka Toteva, Societe des Gens de Lettres, Paris 1995 (in Bulgarian);

- Go 6,000 miles; find air race postponed: Two Young Bulgarian Fliers Travel From Sofia.., The New York Times, Sep 4, 1921, pg. 21;

- Designers shows how stability aids plane safety: new model shows fast climb, By Clarence D. Chamberlin, The New York Times, Mar 16, 1930, pg. XX8;

- Edison forecasts 'eye' for flying: Taking First Ground Lesson, He Hints Device Might Convert Light into Sound...Expounds Theories to Jordanoff, Plane Designer -Sees Future for Helicopter Machines., The New York Times, Oct 3, 1930, pg. 29;

- 'Frozen' Gasoline Curbs Plane from Peril: Dry Ice and Alcohol Cool the Liquid, Thus Reducing Danger From Fire, The New York Times, Jan 16, 1939, pg. 17;

- Jordanoff to issue Aviation Manuals, Publishers Weekly v. 143, Jan 2, 1943

- McLaughlin Joins Jordanoff, The New York Times, Nov 15, 1942, pg. F8;

- Aviation Firm Expands: Jordanoff Co. Leases Additional Space in Madison Ave., The New York Times, Apr 14, 1943, pg. 38;

- Fitzpatrick Joins Jordanoff, The New York Times, Jul 21, 1943, pg. 22;

- Assen Jordanoff: Aviation Pioneer: Stunt Flier Is Dead at 71, Fought in World War I, The New York Times, Oct 19, 1967, pg. 47.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Ganeva, Galina (2023-03-25). "Renaissance Man? This Bulgarian Inventor Did It All". 3 Seas Europe. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- ^ Asen Yordanov

- ^ "Scientific Wonders of Bulgaria: The Bulgarian pilot who taught America how to fly". Archived from the original on 2018-07-11. Retrieved 2018-06-01.

- ^ "Assen Jordanoff Papers | National Air and Space Museum". airandspace.si.edu. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ Composite Gazetteer of Antarctica: Jordanoff Bay.

- ^ "Your wings / By Assen Jordanoff ; drawings by Frank Carlson".

- ^ "Your Wings".

- ^ "Jordanoff's illustrated aviation dictionary".

- ^ "Jordanoff's Illustrated aviation dictionary : By Assen Jordanoff - Catalogue | National Library of Australia".

- ^ https://find.slv.vic.gov.au/discovery/fulldisplay/alma993725883607636/61SLV_INST:SLV [bare URL]

External links

[edit]- 1896 births

- 1967 deaths

- American aerospace engineers

- Members of the Early Birds of Aviation

- Bulgarian inventors

- Bulgarian emigrants to the United States

- People from Sofia

- Eastern Orthodox Christians from the United States

- People from Harrison, New York

- Bulgarian military personnel of the Balkan Wars

- Bulgarian Air Force personnel

- Recipients of the Order of Bravery

- Bulgarian military personnel of World War I

- United States airmail pilots

- 20th-century Bulgarian people

- 20th-century Bulgarian military personnel

- Engineers from New York (state)

- 20th-century American engineers

- 20th-century American inventors