Sterling Price

Sterling Price | |

|---|---|

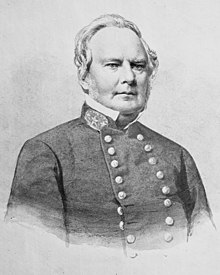

Price in uniform c. 1862 | |

| 11th Governor of Missouri | |

| In office January 3, 1853 – January 5, 1857 | |

| Preceded by | Austin Augustus King |

| Succeeded by | Trusten Polk |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Missouri's at-large district | |

| In office March 4, 1845 – August 12, 1846 | |

| Preceded by | John Jameson |

| Succeeded by | William McDaniel |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 14, 1809 Prince Edward County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | September 29, 1867 (aged 58) St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Resting place | Bellefontaine Cemetery St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Martha Head (m. 1833) |

| Children | 6 surviving, including Edwin |

| Alma mater | Hampden–Sydney College |

| Nickname | "Old Pap" |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Battles/wars | |

Sterling Price (September 14, 1809 – September 29, 1867) was an American politician and military officer who was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army, fighting in both the Western and Trans-Mississippi theater of the American Civil War. He rose to prominence during the Mexican–American War and served as governor of Missouri from 1853 to 1857. He is remembered today for his service in Arkansas (1862–1865) and for his defeat at the Battle of Westport on October 23, 1864.

Early life and entrance into politics

[edit]Virginia

[edit]Sterling Price was born in Prince Edward County, Virginia,[1] near Farmville,[2] to a family of planters of Welsh origin.[3] His parents, Pugh and Elizabeth Price, owned 12 slaves[4] and have been described as "moderately wealthy". Sources disagree as to Sterling's date of birth. The historian Albert E. Castel states that Price was born on September 11, 1809,[3] a date with which the State Historical Society of Missouri agrees.[5] The historian Ezra J. Warner provides the date of birth as September 20, 1809.[1]

Price's father and older brother fought in the War of 1812.[4] Sterling attended a now-unknown grammar school and worked on his father's tobacco plantation before entering Hampden–Sydney College in the fall of 1826. Price did not return for the 1827–28 session for unknown reasons (Price's biographer Robert E. Shalhope speculates that poor examination grades or financial problems could have been the cause), and instead went to study law in Cumberland County, Virginia, under the jurist Creed Taylor.[6]

Records do not indicate that Taylor's law school was in operation for the 1828–29 term, and Price became an assistant to a court clerk in Prince Edward County in 1828. According to Shalhope, Price did not receive "more than a minimal legal education". Shalhope attributes the political climate of Prince Edward County at that time to lasting political beliefs of Price, including support for slavery, a dislike of debt, and tendency to oppose change; the region politically supported John Randolph of Roanoke.[7] The decade of the 1820s saw economic troubles in Virginia, with a mid-1810s surge in tobacco prices being followed by a collapse in prices which ruined many merchants and shippers. Poor economic conditions persisted through the 1820s, and Pugh Price decided to move his family to the state of Missouri, where tobacco production competed with Virginia's tobacco and slavery was legal.[8] The Price family reached Missouri in either 1830[5] or 1831[9] and temporarily settled near Fayette.[10]

Missouri

[edit]The stay in Fayette was designed solely to give Pugh time to select good tobacco-farming ground, and the family moved to the Keytesville vicinity in Chariton County in the summer of 1831.[11] The area was part of a region known as the Boonslick, which contained a number of other former Virginia planters.[12] On May 14, 1833, Price married Martha Head,[13] the daughter of a local judge; the couple would have five sons, one daughter, and several children who did not survive childhood.[3][12] Having entered into a business partnership with one Walter Chiles, Price worked as a merchant, served in the local militia, and began to purchase land both at a nearby river landing and on the prairie in the area.[14]

Price was selected as the area's representative to a Democratic state convention in January 1835, which presented potentially significant political opportunities. The convention was strongly Jacksonian, and nominated Martin Van Buren for the Democratic presidential nominee, Thomas Hart Benton for vice presidential nominee, and a slate of state-level candidates.[15] And then, later that same year, Pugh deeded Sterling most of the land of the Price family farm, making him one of the largest landowners in Chariton County. Price was appointed postmaster for Keytesville in April, and began campaigning for election to the Missouri General Assembly in August.[16] Price was elected to the Missouri House of Representatives, and was placed on two committees. After the session began on November 21, 1836, Price put forth a resolution calling for action on a bill to charter a state bank in Missouri. While a state bank was against Jacksonian principles, a bill chartering a state bank with limits on its powers was passed in January 1837, having been supported by Price and the other politicians from the Boonslick area. Also passed was a bill criminalizing actions that encouraged a slave rebellion. Price, who viewed slavery as a necessary component of Southern aristocracy, viewed this positively and also added an amendment requiring governmental compensation for slaves executed by the state to another bill.

The session adjourned on February 6, and Price returned home.[17]

Missouri Mormon War

[edit]

In 1836, the state of Missouri had established Caldwell County specifically for settlement by members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons). As additional Mormons settled in the area, they began to expand from Caldwell County. Tensions rose over time, and a riot occurred in Gallatin on August 6, 1838, when Mormons attempted to vote outside of Caldwell County.[18] After the riot, Mormon leaders Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon led 150 armed citizens, including a number of Danites, to the Mormon settlement of Adam-ondi-Ahman in Daviess County. Two days later, part of the group visited a local judge, asking him to sign a statement disavowing support for any anti-Mormon violence and containing a promise to uphold the law. The judge considered the statement a violation of his judicial oath not to favor special interest groups, and refused to sign, later traveling with a few others to Richmond, where he issued a complaint against the Mormons for starting frontier war. Arrest warrants were issued for three key Mormon leaders, but they refused to enter custody.[19]

During the election campaign before the Gallatin riot, Price had heard from Josiah Morin, a judge and Missouri State Senate candidate who was on friendly terms with the Mormons, that Morin would likely be forced from his home if he lost his electoral campaign.[20] Represented by Alexander Doniphan and David Rice Atchison, the Mormon leaders stood trial before judge Austin A. King on a farm near the Daviess County line on September 7. King determined that there was enough evidence to warrant a trial before a grand jury, and set the defendants under bail. Doniphan, Atchison, and the defendants returned to the Mormon settlement of Far West. The citizens of Chariton County sent a delegation led by Price to investigate the situation.[21] Along with Edgar Flory, Price attended the trial and then met with Atchison and the Mormon leaders in Far West. Flory and Price wrote a letter back to Chariton County stating that they believed that the actions of the Mormons had not been as reported, and that the legal action had been started by the Daviess County citizens to stir up trouble.[22]

Things appeared to be trending peaceably, but an incident in which Mormon militiamen in Daviess County captured three anti-Mormons and a cache of weapons resparked violence. A force of 400 militiamen under the command of Doniphan was mustered, and the three prisoners were taken back on September 12.[23] Violence recurred in early October, and Doniphan and some militia from neighboring counties were called out again. Before Doniphan's men arrived, the Mormons abandoned the settlement of DeWitt, but then attacked and burned Gallatin and the community of Millport on October 18.[24] Mormon forces and Missouri militia fought the Battle of Crooked Creek on October 25. Exaggerated reports reached Missouri political authorities, and two days later, Governor of Missouri Lilburn Boggs issued the Mormon Extermination Order, which included the statement that "The Mormons must be treated as enemies and must be exterminated or driven from the state".[25]

Boggs also ordered the state militia to deal with the situation; Price commanded the militia from Chariton County.[26] In early November, militia forces took control of Far West, and under the command of John Bullock Clark, Mormons considered to be guilty were rounded up for trial.[27] Price commanded a force that escorted captured Mormon leaders from Independence to Richmond.[28] The men under Price's command treated their prisoners poorly during the movement; Price did not intervene. When the residents of Keytesville met in January 1839, Price was part of a four-person group that drafted a resolution describing their thoughts about the conflict. The resolution supported Boggs's actions and approved of the measures taken to respond to the violence.[29]

Return to the legislature

[edit]Due to his involvement in the conflict with the Mormons, Price did not serve a second term in the state legislature. The mercantile business with Chiles had struggled, so Price dissolved the entity, paid off his share of its debts, and formed a new enterprise with Lisbon Applegate. He was also appointed to a position with the Fayette branch of the recently-approved state bank.[30] By 1840, his farming endeavors had become prosperous, and Price had several dozen slaves.[3] In August 1840, he was elected to another term in the Missouri House of Representatives. Despite his lack of experience in the legislature and young age, there was talk of making Price Speaker of the Missouri House of Representatives, and after the legislature convened in November, he was elected unanimously to that position.[31] The Boonslick faction was strong in Missouri politics at that time. In January 1841, Price was part of a Democratic Party majority that voted against a bill that would have allowed limited partnerships, despite Price having suffered in business ventures previously due to unlimited liability.[32]

As Speaker, Price introduced a series of resolutions about slavery. Governor Thomas Reynolds had sent a letter to the House after receiving communication from the governor of Virginia asking for legal cooperation from the other states that allowed slavery after Governor of New York William H. Seward stated that he would not allow the return of escaped slaves to the south. The resolutions accused Seward of violating the Constitution of the United States, stated that Missourians would make "common cause with the said slaveholding States [sic]", and suggested a boycott of products from New York. While the proposed boycott was struck, the rest of the resolutions passed.[33]

Price was reelected to the legislature in 1842, but the Democratic Party in Missouri was losing internal solidarity, with splits over hard money and soft money currency policies and a feeling in other parts of the state that central Missouri held too much power. A soft money advocate from St. Louis nominated Jesse B. Thompson to run against the hard-money Price in the speaker's election, but Price was elected 72–11.[34] According to Shalhope, Price was "only an adequate parliamentarian and a poor orator", and Claiborne Fox Jackson served as floor leader. Price's role was more to convince legislators to tow the party line and create support for controversial bills. Shalhope writes that Price elicited an "almost blind loyalty among many Missourians"; Price was becoming charismatic in the legislature, although his opponents considered him to be vain.[35]

In 1844, Price campaigned for Benton's reelection to the United States Senate, and then headed the Missouri Democratic Party's nominating convention for major elected offices. Price and his associated bloc were able to influence control over the convention, which eventually supported hard money principles, with the Boonslick faction compromising on the issue of election via districting instead of a general slate by supporting the successful nomination of John Cummins Edwards for governor. However, soft money Democrats would later run their own candidates as independent Democrats, outside of those chosen by the convention. In the end, Benton was reelected and Price was elected to a seat in the United States House of Representatives, with Jackson succeeding him as Speaker.[36]

United States House of Representatives

[edit]

Price arrived in Washington, D.C., where the United States House met, in November 1845, and the 29th United States Congress convened on December 1, with Price in attendance.[37] One of Price's first votes was in favor of an unsuccessful attempt to revive the previously-revoked gag resolution. He also voted to table a bill that would have banned slavery in the District of Columbia, and was part of the majority that voted to admit Texas into the United States. In early 1846, Price voted against a major internal improvements bill, the Rivers and Harbors Bill, despite agreement with some portions of it, as he felt that it unduly benefited special interests. Price's initial position on the Oregon boundary dispute was that the boundary of the United States in the Oregon Country should extend to 54 degrees and 40 minutes north ("54-40 or Fight!"), a position that was popular in Missouri. However, Benton convinced him to support having the boundary at the 49th parallel north, which hurt Price's standing in Missouri.[38]

After the United States' admission of Texas, tensions between the United States and Mexico grew and evolved into small military clashes. On May 11, 1846, President James Knox Polk submitted a message Congress suggesting war with Mexico; Price was part of the majority that voted for it. At the same time back in Missouri, a nominating convention selected James S. Green as the Democratic candidate, rather than renominating Price. Price's opposition to the Rivers and Harbors Bill and his stance on the Oregon boundary had hurt his chances of renomination.[39] Upset at not being renominated, Price resigned his seat in August; he was appointed colonel in one of the Missouri regiments being formed for the war with Mexico, having been suggested for the position by Benton.[40] Price had only introduced two bills during his time in Congress: one related to determining the feasibility of establishing a mail route, and the other calling for Missouri soldiers to be compensated for horses they had lost while serving during the Seminole Wars.[41]

Mexican–American War

[edit]Price's command, the 2nd Missouri Mounted Infantry Regiment,[42] was assigned to serve under the command of Brigadier General Stephen Watts Kearny. Kearny wanted the unit to be raised as infantry, but Price decided on his own to form it as a cavalry unit,[40] a move Shalhope describes as displaying "a certain vanity".[43] The 2nd Missouri left Fort Leavenworth for Santa Fe in the summer of 1846 and arrived on September 28.[44] Price, who had been ill with cholera during the movement,[45] commanded United States forces in Santa Fe, where, according to Castel, he displayed a quarrelsome attitude, a tendency to make decisions so independently that they bordered on insubordination, and a laxness in keeping his troops disciplined.[44] He became quite ill in November and December due to a recurrence of the cholera.[45] Price suffered intestinal problems for the rest of his life, and Shalhope attributes this to the bout with cholera.[46] Kearny's plan had been for Price's arrival in Santa Fe to allow the 1st Missouri Regiment, under the command of Doniphan, to move to Chihuahua, but Doniphan instead was sent on a reprisal mission after the town of Pulvidera was raided by Apaches.[47]

In January 1847, the Taos Revolt occurred, and Charles Bent, the United States Governor of New Mexico, was killed.[48] Price mobilized troops against the revolt, but as he had to keep a garrison in Santa Fe, was initially only able to move towards Taos with 353 men and four mountain howitzers, leaving on January 23. On January 24, Price's men defeated a superior enemy force at the Battle of Cañada, and then received reinforcements which brought his strength to 479 men. After winning the Battle of Embudo Pass, Price's column reached Taos on February 2. The revolters had taken up positions in several buildings at the Taos Pueblo complex, and Price ordered an artillery bombardment of February 3, which was followed by a successful attack the next day. Two leaders of the Taos Revolt were captured: one was executed later in the year, and the other was murdered in prison.[49] According to Shalhope, Price "displayed considerable skill" over the source of the Taos campaign.[50]

Once the Missourians returned to garrison duty, morale and discipline began to fall apart, leading to criticism of Price in the Missouri press.[51] In July, Price received a promotion to brigadier general and became the military governor of Chihuahua,[52] with Benton likely playing a role in the promotion. The enlistment periods for most of his men elapsed in August and September, and they returned home, along with Price. He visited his family and made trips to Jefferson City and St. Louis before returning to Fort Leavenworth in order to return to Santa Fe. After leaving the fort on November 10, Price arrived at Santa Fe in January 1848, where the garrison troops had been better-behaved in his absence. Price quickly sent out new orders to try to prevent discipline from cratering again, although these were not entirely successful.[53]

While in Missouri, Price had been in communication with Adjutant General Roger Jones about leading an expedition into Chihuahua and Durango. After consulting with United States Secretary of War William L. Marcy, Jones replied that such a movement would be more effectively started from elsewhere, although Price was given permission to conduct demonstrations if a Mexican force occupied Chihuahua and threatened New Mexico. After hearing that Mexican General José de Urrea with a large force was threatening American control of the city of El Paso, Price traveled to El Paso on February 23, but learned that the reports were false. Despite his orders to not attack Chihuahua and the lack of a threat to Santa Fe, Price decided to invade Chihuhua anyway. Benton promised to politically shield him from any backlash from the movement.[54] When his supply train ran late, Price decided to begin the advance anyway, and was met by a delegation from the Mexican governor informing Price that the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had been signed and that hostilities were over. Price did not believe the information, and continued on, pursuing a Mexican force that had abandoned Chihuahua City. Many of Price's men's horses began to wear out, and Price was only able to take 250 men to Santa Cruz de Rosales, where the Mexicans had retreated to. After being idle from March 9 to 16 while small parties of reinforcements arrived,[55]

Price attacked on March 16. His men were victorious in close-quarters combat that saw the Mexicans suffer heavy losses. The war had effectively ended well over a month before the battle, but Price received praise in the press and from President Polk despite having ignored the orders to not make the campaign.[56] Price left Chihuahua in July, and was back in Missouri in October, where he had gained sizable political capital. Shalhope writes that Price's success in Mexico led to a willingness to disobey orders, experience with handling volunteer soldiers, and a tendency to ignore logistical matters, all three traits that would extend into a later conflict.[57]

Governor of Missouri

[edit]Price became a slave owner and planter, cultivating tobacco on the Bowling Green prairie. Popular because of his war service, he was easily elected Governor of Missouri in 1852, serving from 1853 to 1857. During his tenure, Washington University in St. Louis was established, the state's public school system was restructured, the Missouri State Teachers Association was created, the state's railroad network was expanded, and a state geological survey was created.[58] Although the state legislature passed an act to increase the governor's salary, Price refused to accept anything more than the salary for which he had been elected.[59]

Price was appointed as the state's Bank Commissioner, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also secured a rail line through his home county, which became part of the Norfolk and Western Railway.[citation needed]

American Civil War

[edit]Struggle for Missouri

[edit]

Price was initially a public supporter of the Union. He backed Stephen A. Douglas for president in 1860.[60] When the states of the Deep South seceded and formed the Confederate States of America, Price opposed secession by Missouri. He was elected presiding officer of the Missouri Constitutional Convention of 1861–1863 on February 28, 1861, which voted against the state leaving the Union. In private, however, Price conspired with pro-Confederate Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson to arm the state's militia with Confederate weapons so they could seize the St. Louis Arsenal and thereby gain control of the city and the state. The plot was foiled in May 1861, when Federal forces under Capt. Nathaniel Lyon seized the militia's Camp Jackson near St. Louis where Confederate weapons had been delivered. No longer able to hide his private support, and using the Federal action as justification, Price gave his public support to the secessionists and joined in requests for the Confederacy to occupy the state.[citation needed]

Jackson appointed Price to command the new Missouri State Guard in May 1861, and Price led his recruits (who nicknamed him "Old Pap") in a campaign to expel Lyon's troops. By then, Lyon's troops had seized the state capital and reconvened the pro-Union Missouri Constitutional Convention. The Convention voted to remove Jackson from office and replace him with Hamilton Rowan Gamble, a pro-Union former chief justice of the Missouri Supreme Court. The climax of the conflict was the Battle of Wilson's Creek on August 10, when Price's Missouri State Guard, supported by Confederate troops led by Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch, soundly defeated Lyon's troops. (Lyon himself died in battle, the first Union general to do so.)[61] Price's troops launched an offensive into northern Missouri, defeating the Federal forces of Colonel James Mulligan at the First Battle of Lexington. However, the Union Army soon sent reinforcements to Missouri, and forced Price's men and Jackson to fall back to the Arkansas border. The Union retained control of most of Missouri for the remainder of the war, although there were frequent guerrilla raids in the western sections.[citation needed]

Still operating as a Missouri militia general (rather than as a commissioned Confederate officer), Price was unable to agree on next steps with McCulloch. This split what might otherwise have become a sizable Confederate force in the West. Price and McCulloch became such bitter rivals that the Confederacy appointed Major-General Earl Van Dorn as overall commander of the Trans-Mississippi district. Van Dorn reunited Price's and McCulloch's formations into a force he named the Army of the West, and set out to engage Unionist troops in Missouri under the command of Brigadier-General Samuel R. Curtis. Now under Van Dorn's command, Price was commissioned in the Confederate States Army as a Major-General on March 6, 1862.[62]

Outnumbering Curtis's forces, Van Dorn attacked the Northern army at Pea Ridge on March 7–8. Although wounded in the fray, Price pushed Curtis's force back at Elkhorn Tavern on March 7, but the battle was lost on the following day after a furious Federal counterattack.[citation needed]

Western Theater

[edit]Price, now serving under Van Dorn, crossed the Mississippi River to reinforce Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard's army in northern Mississippi following Beauregard's loss at the Battle of Shiloh. Van Dorn's army was positioned on the Confederate right flank during the Siege of Corinth. During Braxton Bragg's Confederate Heartland Offensive, Van Dorn was sent to western Mississippi, while Price given command of the District of Tennessee. As Bragg marched his army into Kentucky, Bragg urged Price to make some move to assist him. Not waiting to re-unite with Van Dorn's returning forces, Price seized the Union supply depot at nearby Iuka, but was driven back by Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans at the Battle of Iuka on September 19, 1862. A few weeks later, on October 3–4, Price (under Van Dorn's command once more) was defeated at the Second Battle of Corinth.

Van Dorn was replaced by Maj. Gen. John C. Pemberton, and Price, who had become thoroughly disgusted with Van Dorn and was eager to return to Missouri, obtained a leave to visit Richmond, the Confederate capital. There, he obtained an audience with Confederate President Jefferson Davis to discuss his grievances, only to find his own loyalty to the South sternly questioned by the Confederate leader. Price did secure Davis's permission to return to Missouri—minus his troops. Unimpressed with the Missourian, Davis pronounced him "the vainest man I ever met."[63]

Trans-Mississippi Theater

[edit]Price was not finished as a Confederate commander, however. He contested Union control over Arkansas in the summer of 1863, and while he won some of his engagements, he was not able to dislodge Northern forces from the state, abandoning Little Rock for southern Arkansas.[citation needed]

Missouri Expedition

[edit]

Despite his disappointments in Arkansas and Louisiana, Price convinced his superiors to permit him to invade Missouri in the fall of 1864, hoping yet to seize that state for the Confederacy or at the very least imperil Abraham Lincoln's chances for reelection that year. Confederate General Kirby Smith agreed, though he was forced to detach the infantry brigades originally detailed to Price's force and send them elsewhere, thus changing Price's proposed campaign from a full-scale invasion of Missouri to a large cavalry raid. Price amassed 12,000 horsemen for his army, and fourteen pieces of artillery.[64]

The first major engagement in Price's Raid occurred at Pilot Knob, where he successfully captured the Union-held Fort Davidson but needlessly subjected his men to high fatalities in the process, for a gain that turned out to be of no real value. From Pilot Knob, Price swung west, away from St. Louis (his primary objective) and toward Kansas City, Missouri, and nearby Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Forced to bypass his secondary target at heavily fortified Jefferson City, Price cut a swath of destruction across his home state, even as his army steadily dwindled due to battlefield losses, disease, and desertion.[citation needed]

Although he defeated inferior Federal forces at Boonville, Glasgow, Lexington, the Little Blue River and Independence, Price was ultimately boxed in by two Northern armies at Westport, located in today's Kansas City, where he had to fight against overwhelming odds.[citation needed] This unequal contest, known afterward as "The Gettysburg of the West", did not go his way, and he was forced to retreat into hostile Kansas. A new series of defeats followed, as Price's battered and broken army was pushed steadily southward toward Arkansas, and then further south into Texas. Price's Raid was his last significant military operation, and the last significant Confederate campaign west of the Mississippi.[citation needed]

Notable battles

[edit]Some of Price's notable battles during the American Civil War are listed here in order of occurrence, and indicating whether he was in overall command and whether the battle or engagement was won or lost:

| Battle | In command | Result | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carthage, Missouri | No | Won | |

| Wilson's Creek, Missouri | No | Won | |

| Lexington, Missouri | Yes | Won | |

| Pea Ridge, Arkansas | No | Lost | |

| Iuka, Mississippi | Yes | Lost | |

| Corinth, Mississippi | No | Lost | |

| Helena, Arkansas | No | Lost | |

| Bayou Fourche, Arkansas | see notes | Lost | in overall command, though not commanding on the battlefield |

| Prairie D'Ane, Arkansas | Yes | Lost | |

| Jenkins' Ferry, Arkansas | No | Lost | Confederates took the field, but the Union force escaped |

| Pilot Knob, Missouri | Yes | Lost | Price took the fort, but the Union force escaped |

| Glasgow, Missouri | see notes | Won | in overall command, though not commanding on the battlefield |

| Little Blue River, Missouri | Yes | Won | |

| Independence, Missouri | Yes | Won | |

| Westport, Missouri | Yes | Lost | |

| Mine Creek, Kansas | Yes | Lost |

Emigration to Mexico

[edit]Rather than surrender, Price emigrated to Mexico, where he and several of his former compatriots attempted to start a colony of Southerners. He settled in a Confederate exile colony in Carlota, Veracruz. There Price unsuccessfully sought service with the Emperor Maximilian. When the colony failed, he returned to Missouri.

Death

[edit]

While in Mexico, Price started having severe intestinal problems, which grew worse in August 1866 when he contracted typhoid fever. Impoverished and in poor health, Price died of cholera (or "cholera-like symptoms") in St. Louis, Missouri. The death certificate listed the cause of death as "chronic diarrhea".[65] Price's funeral was held on October 3, 1867, in St. Louis, at the First Methodist Episcopal Church (on the corner of Eighth and Washington). His body was carried by a black hearse drawn by six matching black horses, and his funeral procession was the largest to take place in St. Louis up to that point. He was buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery.[66]

Honors

[edit]

- During the American Civil War, a wooden river steamer built at Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1856 as the Laurent Millaudon was taken into Confederate service and renamed the CSS General Sterling Price. Participating in actions near Fort Pillow, Tennessee, on May 10, 1862, she damaged two Federal gunboats before being temporarily put out of action. The General Price was sunk during the First Battle of Memphis, raised, repaired, and served in the Union Navy under the name USS General Price although she was still referred to as the "General Sterling Price" in Federal dispatches. As a Union ship, she served in the Vicksburg and Red River campaigns. The General Price was sold for private use after the war.[67]

- Camp No. 31 (organized October 13, 1889) of the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) in the city of Dallas, Texas, was named after him.[68]

- A monument to Price stands in the Springfield National Cemetery (Springfield, Missouri). Dedicated August 10, 1901, the bronze figure honors all Missouri soldiers and General Price. It was commissioned by the United Confederate Veterans of Missouri.

- A statue of Price stands in Price Park, Keytesville, Missouri, which is also the location of the Sterling Price Museum in his honor.

- The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) commissioned Jorgen Dreyer in 1939 to create a bust of Price.[69] It is in the Visitor Center of the Battle of Lexington Missouri Historic Site.

- Camps No. 145 (St. Louis) and Camp No. 676 (Littleton, Colorado) of the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) are named after him.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Warner 2006, p. 246.

- ^ "Sterling Price". History, Art, and Archives: United States House of Representatives. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Castel 1993, p. 3.

- ^ a b Shalhope 1971, p. 4.

- ^ a b "Sterling Price". State Historical Society of Missouri. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 5–7.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Warner 2006, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, p. 14.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Shalhope 1971, p. 16.

- ^ "Sterling Price, 1853–1857". sos.mo.gov. Missouri Digital Heritage. Retrieved December 29, 2021.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 23–26.

- ^ Launius 1998, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Launius 1998, pp. 65–66.

- ^ LeSueur 1987, p. 60.

- ^ Launius 1998, p. 67.

- ^ LeSueur 1987, p. 84.

- ^ Launius 1998, pp. 68–70.

- ^ Launius 1998, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Launius 1998, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, p. 27.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 27–28.

- ^ LeSueur 1987, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, p. 28.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 37–39.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 41–46.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 49–54.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 52–54.

- ^ a b Castel 1993, p. 4.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, p. 54.

- ^ Eisenhower 2000, p. 234.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, p. 58.

- ^ a b Castel 1993, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b Welsh 1995, p. 177.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, p. 59.

- ^ Eisenhower 2000, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Castel 1993, p. 5.

- ^ Eisenhower 2000, pp. 237–240.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, p. 66.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Dupuy, Johnson & Bongard 1992, p. 612.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 66–69.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Simmons, Marc (October 1, 2010). "Trail Dust: Gen. Sterling Price Won Pointless Victory in 1848". Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ^ Shalhope 1971, pp. 74–77.

- ^ Governor's Information: Sterling Price. Retrieved November 22, 2009. Archived December 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pictorial and Genealogical Record of Greene County, Missouri Archived March 6, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, entry: "General Sterling Price"; The Library, Springfield, Missouri. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ Pollard 1867, p. 155.

- ^ "Wilson's Creek". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ Eicher, p. 440.

- ^ Sterling Price. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ^ "Sterling Price (1809–1867)", The Latin Library. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- ^ Welsh, Jack D. (1995). Medical Histories of Confederate Generals. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. pp. 177. ISBN 0-87338-505-5.

- ^ Shalhope, Robert E. (1971). Sterling Price: Portrait of a Southerner. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. pp. xi, 290. ISBN 978-0-8262-0103-4.

- ^ History of the ship, CSS General Sterling Price

- ^ Charter, constitution and by-laws, officers and members of Sterling Price Camp, United Confederate Veterans, Camp No. 31: organized, October 13, 1889, in the city of Dallas, Texas. published 1893, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- ^ Sedalia (MO) Democrat, p. 10, September 17, 1939.

Sources

[edit]- Castel, Albert E. (1993) [1968]. General Sterling Price and the Civil War in the West. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-1854-0.

- Davis, Dale E. Assessing Compound Warfare During Price's Raid. Ft. Leavenworth, KS: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 2004. OCLC 70153559.

- Dupuy, Trevor N.; Johnson, Curt; Bongard, David L. (1992). Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-270015-5.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Eisenhower, John S. D. (2000) [1989]. So Far From God: The U.S. War with Mexico, 1846–1848 (Oklahoma Paperback ed.). Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3279-2.

- Gifford, Douglas L. The Battle of Pilot Knob: Staff Ride and Battlefield Tour Guide. Winfield, MO: D.L. Gifford, 2003. ISBN 978-1-59196-478-0.

- Launius, Roger D. (1998). "Alexander William Doniphan and the 1838 Mormon War in Missouri". John Whitmer Historical Association. 18: 63–110. JSTOR 43200103.

- LeSueur, Stephen C. (1987). The 1838 Mormon War in Missouri. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-6103-8.

- Lexington Historical Society. The Battle of Lexington, .... Lexington, MO: Lexington Historical Society, 1903. OCLC 631462805.

- Pollard, Edward A. (1867) [1866]. The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates: Comprising a Full and Authentic Account of the Rise and Progress of the Late Southern Confederacy—the Campaigns, Battles, Incidents, and Adventures of the Most Gigantic Struggle of the World's History. New York, NY: E.B. Treat & Co., Publishers. ISBN 9780517101315.

- Rea, Ralph R. Sterling Price, the Lee of the West. Little Rock, AR: Pioneer Press, 1959. OCLC 2626512.

- Shalhope, Robert E. (1971). Sterling Price: Portrait of a Southerner. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-0103-2.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Twitchell, Ralph Emerson. The History of the Military Occupation of the Territory of New Mexico from 1846 to 1851. Denver, CO: Smith-Brooks Company Publishers, 1909. OCLC 2693546.

- Warner, Ezra J. (2006) [1959]. Generals in Gray (Louisiana Paperback ed.). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3150-3.

- Welsh, Jack D. (1995). Medical Histories of Confederate Generals. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-505-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Forsyth, Michael J. The Great Missouri Raid: Sterling Price and the Last Major Confederate Campaign in Northern Territory (McFarland, 2015) viii, 282 pp.

- Geiger, Mark W. (2010). Financial Fraud and Guerrilla Violence in Missouri's Civil War, 1861–1865. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15151-0.

- Sinisi, Kyle S. The Last Hurrah: Sterling Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.) xviii, 432 pp.

External links

[edit]- Sterling Price at Find a Grave

- Sterling Price at The Historical Marker Database (HMdb.org)

- Sterling Price at the National Governors Association

- Works by or about Sterling Price at the Internet Archive

- 1809 births

- 1867 deaths

- 19th-century American politicians

- American military personnel of the Mexican–American War

- American expatriates in Mexico

- American people of Welsh descent

- American refugees

- American proslavery activists

- Confederate expatriates

- Burials at Bellefontaine Cemetery

- Confederate States Army major generals

- Deaths from cholera in the United States

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Missouri

- Democratic Party governors of Missouri

- Hampden–Sydney College alumni

- Missouri State Guard

- People from Bowling Green, Missouri

- People from Keytesville, Missouri

- People from Prince Edward County, Virginia

- People of Missouri in the American Civil War

- People of the Taos Revolt

- Price's Missouri Expedition

- Refugees in Mexico

- Speakers of the Missouri House of Representatives

- Deaths from diarrhea

- Members of the United States House of Representatives who owned slaves